Joyce Glasser reviews Honey Boy (December 6, 2019), Cert. 15, 94 min.

If autobiographical films are not a form of nostalgia, they are a form of self-therapy. Samuel Fueller dealt with his WWII PTSD in The Big Red One, and Scottish filmmaker Bill Douglas relieved the misery of his youth through his famous 1970’s kitchen sink trilogy. Banned Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi (with Kambuzia Partovi) shot his 2013 film Closed Curtain behind the curtains of his remote beach home to fend off thoughts of suicide. In the past year alone, photographer Richard Billingham turned to film to purge his abusive, dysfunctional childhood in Ray & Liz; Joanna Hogg re-played her life in 1982 to examine where manipulation ended and complicity began in The Souvenir; and Pedro Almodóvar confronted the pain in past relationships in Pain and Glory.

Now Shia LaBeouf, 33, scores a double-first. He wrote Honey Boy

during a court-ordered rehabilitation after drunk and disorderly conduct in Georgia where he was starring in The Peanut Butter Falcon. And in Honey Boy

he plays his own abusive, alcoholic, womanising father, the man in part responsible for the behaviour that landed LaBeouf in court. LaBeouf’s performance is outstanding, on a par with American Honey, though his character’s life in both films is anything but sweet.

LaBeouf does not direct himself in this intensive role. He entrusts his script to Alma Har’el, the Israeli American director of Bombay Beach, a 2011 documentary about a small community of misfits living in a unique shanty town in California, way below sea level. In some ways it is reminiscent of the downmarket Hollywood motel where twelve-year-old series actor Otis Lort (Noah Jupe) lives with his father and guardian James (LaBeouf) an otherwise unemployed ex-rodeo clown and ex-con.

Har’el described Bombay Beach as a film about “how things co-exist, all the wrongs and the rights together, the love and the violence, the broken dream and the persistence of dreams. Even though the dream is broken, you can still see the people.” And there is something of that in Honey Boy.

If you are unfamiliar with LaBeouf’s films and life, you might be lost in the opening scenes in which Har’el captures the wild behaviour of 22-year-old Otis Lort (Lucas Hedges), first on the set of an action franchise film (LaBeouf stared in several Transformers films) and then on a night out with his co-star that culminates in a car crash. Otis is forced into rehab where Dr. Moreno (Laura San Giacomo) diagnoses his problem as PTSD. Otis, still in disruptive mode, threatens to walk out, but Dr. Moreno reminds him the alternative is a custodial sentence.

The film crosscuts between the rehab setting in 2005 and 1995 when young Otis is the child star of a sitcom (young LaBeouf starred in The Disney Channel’s Even Stevens). He is living in a seedy motel with his divorced father. Otis speaks to his mother on the phone, but we never learn why she is not with her son.

LaBeouf has said that growing up on a studio set was the best thing that ever happened to him, and in the film, we see that life off the set was no doubt the worst. He is continually subjected to his ex-addict, ex-felon father’s bullying and physical and mental abuse.

For Otis, James is one big embarrassment. Otis’s mother has put him in a “Big Brother” programme to have a positive role model around. When his ‘big brother’, a mild-mannered man named Tom (Clifton Collins Jr.), arrives at the poolside to take Otis to a baseball game James threatens him, telling him to stay away form his son. When Tom tries to talk to him, James pushes him in the pool.

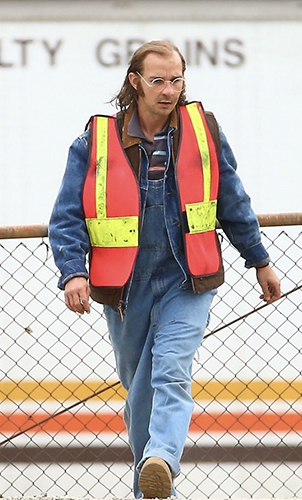

Shia LaBeouf in Honey Boy

James’s presence as Otis’s legal guardian hampers his show business career in other ways, too. When he is offered a role on a film in Canada, Otis’s mother says that James might not be able to accompany him because he is on the sex-offender register. In this devastating scene, Otis conveys messages between his angry mother and his screaming, ballistic father. Equally hard to watch is a scene where James belittles his son, mocking his undeveloped sexual organs.

It is in the scenes when James is on his own that we begin to look at him, not as Otis’s father, but as a man who has made a mess of his life and is humiliated by the fact that his adolescent son is not only his boss, but also has to support him. You can almost see LaBeouf’s pain as he tries to understand his father as an individual in these scenes, a man who cannot seem to stay away from drugs (he goes into a strip joint in town to score and grows marijuana on the side of a motorway) and women (we see him chatting up a crew member on the set).

He has failed in his career, as a husband and as a father, but we do not know whether the booze and drugs are the cause, or whether some underlying trauma in his own life has driven him to these substances. But it is obvious that he takes out his self-disgust on Otis and is too proud to admit how much he admires, if not loves, and depends on him.

Though more dependent than many boys his age, Otis has also been living in a bubble, which is what makes a scene in which he befriends a caring, young prostitute in the motel all the more moving. Jupe is a charmer and a fine child actor but at times LaBoeuf puts words into his mouth that blur the lines between 1995 and 2005, if not 2017. It is as if the adult LaBoeuf is speaking to his father when young Otis, tells him, ‘You know I’m doing you a favour paying you to be my chaperone. Who else is going to give a felon a job?’

Though more film time is devoted to the 1995 period, the film drops a notch when it switches to 2005. This is not only because therapy scenes are so familiar, from recent films like Rocketman, A Million Little Pieces, and The Miseducation of Cameron Post, but also because Lucas Hedges has, since Manchester by the Sea in 2016, specialised in playing troubled young men. This year he has appeared in a rehab setting in Boy Erased and as an escapee from an institution in Ben is Back.

While LaBoeuf wants to make peace with his father, the relatively upbeat ending is discomforting, particularly as LaBoeuf’s recent arrest in Georgia suggests that there may be a ceasefire, but peace is not yet assured.

You can watch the film trailer here: