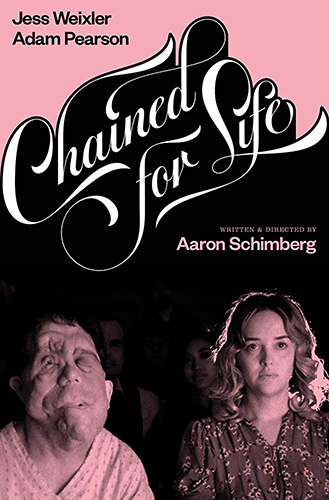

Joyce Glasser reviews Chained for Life (October 25, 2019), Cert. 15, 92 min.

Most films that feature ‘freaks’ are either set in the circus, like the classic 1932 Freaks, set in a circus and Hugh Jackman’s The Greatest Showman, or are horror/exploitation films like 1981’s The Fun House or 1995’s Castle Freaks. Occasionally, as in 2004’s Hellboy and the recent The Addams Family, the ‘freaks’ are the protagonists with whom we can empathise and who have personalities unrelated to their deformities. American director Aaron Schimberg’s strange, and clever film Chained for Life has it both ways, as it is both a politically incorrect horror film and a satirical look at a politically correct film crew coming to terms with ingrained notions of beauty.

The film within a film technique, is highly effective and enables Schimberg to open with a treatise on beauty from the influential New Yorker critic Pauline Kael’s review of Funny Girl (1968). ‘Actors and actresses who are beautiful start with an enormous advantage because we love to look at them. Actors and actresses are usually more beautiful than ordinary people, and why not? Why should we be deprived of the pleasure of beauty…? The handsomer they are, the more roles they can play…’

The film within a film technique, is highly effective and enables Schimberg to open with a treatise on beauty from the influential New Yorker critic Pauline Kael’s review of Funny Girl (1968). ‘Actors and actresses who are beautiful start with an enormous advantage because we love to look at them. Actors and actresses are usually more beautiful than ordinary people, and why not? Why should we be deprived of the pleasure of beauty…? The handsomer they are, the more roles they can play…’

Cut to a Victorian formal mental hospital, the fittingly Gothic set for Herr Director’s (Charlie Korsmo) horror movie in which a beautiful blind woman named Freda (Jess Weixler), falls in love with a severely disfigured man (Adam Pearson). We piece together the plot of the horror film as it is being shot, but, taking its cue from Tom DiCillo’s film-within-a-film Living in Oblivion and Francois Truffaut’s Day for Night, we see more of the behind the scenes interaction among the characters than the actual filming. The point of this film-within-a-film is that the two worlds intermingle in interesting ways.

In a long scene in which Mabel, who might have had a bit to drink, questions whether the director or the ‘freaks’ are authentic, Schimberg plays with actors’ insecurity about their own authenticity, talent and beauty. ‘I thought Siamese twins had been phased out’ Mabel comments, noticing the youthful sisters are ‘only’ joined at the shoulder and operations are commonplace. A hermaphrodite is also subjected to scrutiny. When Mabel asks about the identity of a tall, older woman with scar tissue all over her face, she learns the woman is there to play Freda – after the fire. Mabel becomes haunted by this vision because she realises that only an accident, or a tiny gene, is the fine line that separates her from this woman and Rosenthal (Sammy Mena).

Schimberg carries this one step further – and perhaps an ambitious step too far – in blurring the line between the real and fictional story to such an extent that we are confused and lose the narrative thread. At one point, Mabel’s psychological state is close to matching her character’s and she has a dream that, for a while, we incorporate into the present-day story. Still, Mabel’s narrative recovers in the inspired ending, which is a vast improvement over Schimberg’s self-indulgent and largely incomprehensible previous feature, Go Down Death.

But if the film-with-in-a-film structure has antecedents, the style Schimberg adopts, particularly in the handling of sound, is closer to Robert Altman’s Nashville in which the characters and microphones are continually roving and switched on. We pick up bits of jokes and gossip in the distance as if they are overheard by others.

If Truffaut’s cast fed into Paul Kael’s observations, Herr Director is bringing in a busload of circus folk with physical abnormalities from a specialist agency. They apparently all sleep in the same room, as if they are children or second-class citizens. All of the ‘freaks’ have minor roles save for Rosenthal (Pearson) who becomes the phantom of the hospital or the beast in the castle with Beauty.

What we learn about the film and director is a combination of rumour, second-hand information from snippets of conversations and gossip to fill a void. The title of the movie will be God’s Mistakes in German and is the story of a mad doctor and evil nurse who operate on disabled patients to remove their disabilities so they can re-enter society. This reminds us of the far more recent gay conversion therapy (films like Boy Erased and Ben is Back) in which a bit of therapy can reverse nature.

If your mind is, however, directed to the Nazi’s solution to the unfair burden that disabled people place on society, do not be surprised. For an American, Schimberg’s satirical touches are sure, but subtle. In an on-set interview Mabel is asked, ‘It’s his first American film?’ ‘Yes’ she replies, but it still feels European which is what I like about it.’

Schimberg may even have in mind a Nazi propaganda film called I Accuse, about a doctor who kills his disabled wife in a mercy killing. And he might be aware of the Nazi poster campaigns in which disabled people are referred to as ‘freaks. Throughout the production there are rumours that the director was raised in a circus and is not really German.

Mabel, who is the celebrity actress here, and used to being told how beautiful she is, is insecure about her talent and knows she is far from the A-list. Mabel wants to establish a relationship with Rosenthal to make the film as authentic as possible – and because the film calls for a sex scene between them that both are dreading.

As a way of breaking the ice, or, more likely, to force Mabel to establish eye contact with him, Rosenthal tells her he is having trouble memorising his lines and suggests perhaps she can help. This evolves into an acting lesson in which Mabel demonstrates how to express the basic emotions, using facial expressions that Rosenthal is probably incapable of forming due to his disfigurement. But Mabel has her limitations, too. She has no trouble in expressing happiness and sadness, but when Rosenthal asks her to express empathy, she never finds the right look. ‘Well, Rosenthal remarks kindly, ‘it’s a lot like pity, but you’re really very talented.’ Schimberg knows how to cut a scene just after the punchline, and sometimes, he lives it for the audience to conjure it up.

In a variation on the theme of our obsession with physical beauty and its opposite Max (Stephen Plunkett), the actor who plays the mad scientist, sees Rosenthal taking pictures and rushes out to get a photo of Rosenthal and himself as though they are buddies, or Rosenthal is Tom Cruise. ‘I like you’, Max insists, ‘you’d make a great Richard III’, then, realising how it sounded, fumbles to explain what Rosenthal would bring to the role. In this scene, as in the marvellous ‘step out of the shadows into the light’ scene, Rosenthal scores points that go over the heads of this arrogant actor and the pretentious director respectively.

You can watch the film trailer here: