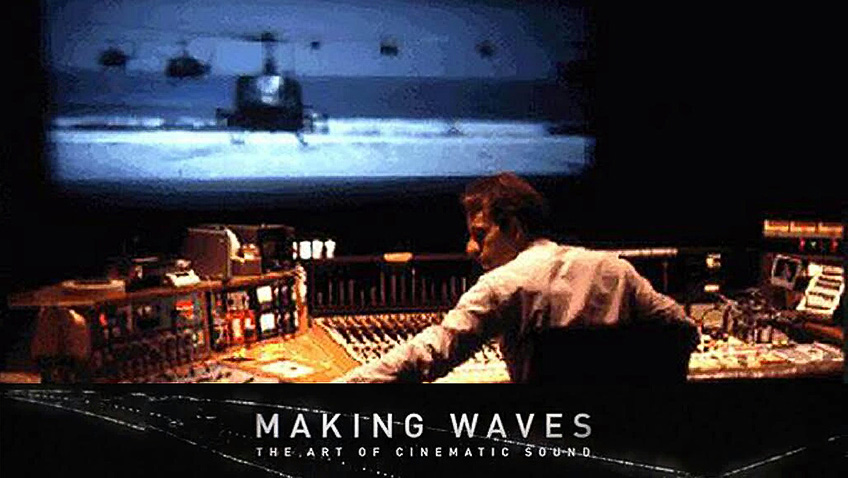

Joyce Glasser reviews Making Waves: The Art of Cinematic Sound (Nov 1, 2019), Cert. 12, 94 min.

This enthralling documentary about a traditional male preserve, the highly technical world of cinema sound, is made by three female producers (one of whom is the writer). This tells you something about the changing face of cinematic sound, once relegated to the minor technical awards, and ever a poor cousin to image. Along with sound, women sound recordists, editors and mixers like Teresa Eckton (Saving Private Ryan), Lora Hirschberg (The Dark Knight), Cecelia Hall (Top Gun), and Bobbi Banks (Selma) are finally being recognised – and slowly infiltrating the male ranks.

Steven Spielberg, whose Saving Private Ryan won a Best Sound Academy Award, tells the audience: ‘I’ve always been of the belief that our ears lead our eyes to where the story lies.’ By the end of this information-packed film, full of anecdotes from many of America’s top directors and sound artists, you will be a convert. A major criticism of the film is not so much that it does not have the time or space to cover world cinema, but that the title does not reflect this geographical limitation.

While on the subject of Saving Private Ryan, we are introduced to Gary Rydstrom, who won two Oscars for his sound work on that film. ‘What strikes me the most about Saving Private Ryan’ Rydstrom says as we listen to clips, ‘is that it was designed to tell a part of the story that it’s not showing you.’ Among Rydstrom’s greatest hits are Terminator 2: Judgement Day, Jurassic Park, Titanic, and Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace, where he worked under his mentor, Ben Burtt (E.T., Indiana Jones).

Later in the film, which runs roughly in chronological order, we learn how Burtt created Chewbacca’s voice from recordings of walruses, lions, camels, bears, tigers, and other animals with various recordings mixed at different ratios to express his difference utterances. Like the scriptwriter, and the actor, the sound artist could also create a character – or contribute – as with R2D2 – that defining touch.

‘It wasn’t always like this’ we are reminded before being treated to an entertaining history of the development of sound. ‘When it all started, movies were silent.’ But Ben Burtt tells us that Thomas Edison originally developed the motion picture camera ‘because he wanted image to go along with his phonograph.’ The problem was that sound and film tracks run at different speeds and for years, there was no way to sync them. So, Edison’s project of integrating the two was abandoned.

Burtt tells us that nonetheless, because everyone knew that music would ‘elevate the experience’, films were projected with live orchestras and, for some films, people travelled around with the orchestras making sound effects (the first Foley artists). In 1926 Don Juan starring John Barrymore had a synchronised music track and the following year, with The Jazz Singer, Al Jolson’s voice was recorded. It was not the singing voice that delighted the audience, however, but the speaking voice.

While sound was here to stay, there was a drawback. Directors had previously been free to film in remote locations – a clip of Lilian Gish’s woman in jeopardy on an icy river in Way Down East of 1920. With sound, productions were stuck in sound studios that blocked out the world. In an amusing illustrative clip, we see the scene in Singin’ In the Rain with people rushing around saying “quiet”. Another constraint was that microphone range was so short the actors couldn’t move. Cue the hilarious scene where Lina Lamont (Jean Hagen) is not audible due to the position of the microphones while Gene Kelly is uttering “I love you” with no response.

Even with this problem resolved, directors could not get the sounds they wanted on set with microphones alone: the sounds just weren’t there. It is only at the end of the film that we learn that much of what you hear is added after principal photography: ADR (additional dialogue recorded) and Foley, in which a Foley artist, watching the film footage, recreates sounds to match the action by using a wide variety of objects.

But it was not until the pioneering Murray Spivack created sound effects for King Kong in 1933 that cinema had its first sound designer (a term not yet in existence). We hear Spivack recall how he created the voice for Kong by playing the tiger growl (that he recorded in a zoo) backward over a lion roar, forward. Many of his techniques are still used today. But Spivack was locked away in some corner of the music department and studios saved time and money repeating the same generic sounds over and over again.

In 1941 the biggest innovation came from radio, particularly Orson Welles. He incorporated many of his techniques from The Shadow and War of the Worlds in Citizen Kane. While Alfred Hitchcock (a clip from The Birds), David Lean (Lawrence of Arabia) and Stanley Kubrick (2001: A Space Odyssey) represent directors recognising the importance of sound in creating not only atmosphere, but character, in the 1950s and 1960s with the competition from television, live news and music, corporate Hollywood watched the bottom line. In 1962 12,000 union members were out of work and film production dropped 40%.

Then a confluence of talent from UCLA and USC film schools emerged to save the day. Walter Murch, the 3-time-Academy Award winning sound designer and film editor who was to change sound design forever with Apocalypse Now, met George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola. And thanks to the freedom of the portable sound recorder, the Negra, they set up American Zoetrope in San Francisco. Dropped by Warner Brothers after THX 1138, Coppola was approached to direct “a sleazy gangster film” that 12 other directors had turned down. It was The Godfather.

But the innovative soundtrack of The Godfather was released in the theatres in 1972 in “mono” like Gone with the Wind in 1939. By the mid-to-late 1960s, with The Beatles’ Revolver, the music industry was switching to stereo. Sound editors like Mark A. Mangini (Mad Max, Blade Runner) wanted it for cinema. Enter Dolby.

But creating soundtracks needed time. Musically trained Coppola set aside a budget for sound, and so did Barbra Streisand who used her own money to ensure four months (as opposed to the usual 7 weeks) on A Star is Born. Laughing at the recollection she adds that when it was a hit, Warner Brothers reimbursed her!

There are many other fabulous anecdotes (Pixar) and revelations (the importance of Altman’s Nashville), but several key recent films are conspicuous by their absence. The filmmakers’ decision to put the technical foundations of how you build a soundtrack at the end of the film is a tough one to call. While it makes sense to have it at the beginning, frontloading the film with some big names and engaging clips and anecdotes is perhaps more inviting.

You can watch the film trailer here: