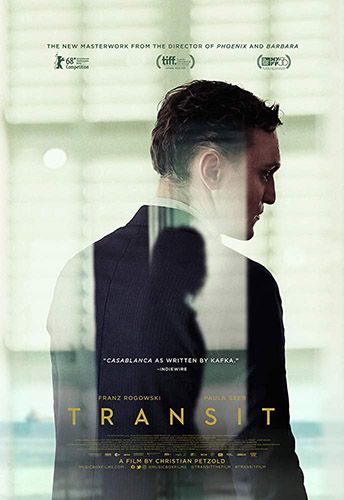

Joyce Glasser reviews Transit (August 16, 2019), Cert. 12A, 101 min.

Christian Petzold’s intriguing, if perhaps overly ambitious new film Transit begins as a nail-biting, fast-paced, political thriller and ends in a Kafkaesque limbo. Here desperate fugitives, deadened by hunger and bureaucracy, wait in fear for visas while lost and dead souls meet in cafés. In addition to many of Petzold’s recurrent motifs, such as appearance and identity, the 58-year-old’s films, including Ghosts, Yella, Barbara, and Phoenix are imbued with the stain of WWII and the trauma of East Berlin. In an interview, Petzold said that he used the Brechtian technique of transposing the past into the present to see what would happen.

He does this by folding historic events from the 1944 novel Transit Visa

He does this by folding historic events from the 1944 novel Transit Visa, written by Anna Seghers, into a vague present and turning a group of German speaking fugitives, stuck in the port of Marseille, into the victims of a French police state. There are no mobile phones or internet, but the French police wear riot gear as though the film is a reversed political allegory. This might be why a suicidal Jewish architect (Barbara Auer) admires a 2013 building by Algerian-born architect Rudy Ricciotti that is, itself, linked to a 17th century fort. There is so much to commend in this thought-provoking, original and mesmerising film that it is unfortunate that aspects of this transposition, along with a frustrating love triangle and an annoying voice-over relating the story to us (or someone), detract from the film’s power.

Anna Seghers (born Anna Reiling) was a Jewish, communist novelist who, after being released by the Gestapo, moved to Paris and, in 1940, fled with thousands of others to Marseille from where, a year later, she sailed to Mexico. The protagonist of Transit, Georg (Franz Rogowski) arranges to follow a similar itinerary, but a series of coincidences and attachments put his already tenuous paperwork in jeopardy.

Although Petzold sets his film in the summer of 1942 when the French, acting under German orders, are rounding up Parisian Jews in the Vélodrome d’Hiver (the subject of Roselyne Bosch’s 2010 film The Round Up, Georg, an electrician, is lying low in a nondescript bar. A journalist friend under surveillance asks Georg to drop off two letters to his friend Weidel, a communist novelist. When he returns, they will drive to Marseille. But Georg learns that Weidel has committed suicide and he returns to the bar with the letters and Weidel’s last manuscript that the distraught hotel owner’s daughter gave him. Significantly, to avoid detection, she arranged to have Weidel buried in an unmarked grave without registering his death.

Approaching the café, Georg sees that the journalist is being arrested. Georg himself narrowly escapes, fleeing Paris on a freight car with Heinz (Ronald Kukulies), a badly-wounded friend who does not survive the journey. In the train Georg reads the letters: one from the Mexican Consulate confirming Weidel’s papers and travel money await him, and the other from Weidel’s estranged wife, Marie, urging him to join her to begin their new life together in Mexico. An earlier letter, that, we are told, Georg finds inserted in the manuscript, suggests that Marie had abandoned Weidel. But now she awaits him and her exit papers somewhere in Marseille.

Marseille is saturated with sunshine, reminiscent of Albert Camus’ The Plague and The stranger

, with their references to the Algerian War and the recent problems with immigrants in France. But the sun does not have poetic connotations. The rooms are overpriced; the hotel owners are collaborators; and, ironically, they require proof of a guest’s imminent departure and exit visa before giving guests a room.

Georg goes to the Mexican Consulate with a story about Weidel only to realise that the officials assume he is Weidel, and he plays along. Georg’s interviews with both the Mexican Consul (Alex Brendemühl) and his suspicious American counterpart (Trystan Pütter) from whom Georg requires a transit visa, are filled with tension and wonderfully clever (recall that Georg’s only knowledge of Weidel comes from having read his manuscript and letters). When tested by the American consul, Georg recites a pointed parable taken from Weidel’s manuscript, which is in fact, from Kafka.

The desperate, wretched people Georg’s meets in the long queues for papers are both real and pitiable. Amongst them is a conductor losing his mind and the aggrieved Jewish architect (Auer) who has been left with her former clients’ two large dogs when they obtained passage before her.

Petzold’s films have a supernatural dimension to them, and many times, the links between the living and the dead are as mysterious as those between the present and the past. Whilst Georg is alone in the city, a beautiful young woman (Paula Beer) approaches him on several occasions between his hang-out, the Bar Mont Ventoux and the US Consulate. When Georg turns around, she is confused and unsettled, clearly mistaking him for someone else.

Georg locates Heinz’s family in a dismal housing estate. He breaks the news to Heinz’s wife (Maryam Zaree) only to notice that her young son, Driss (Lilien Batman) is signing to his deaf and mute mother. Georg and Driss spend time together making it painful for Driss, who has just lost one father, to accept Georg’s departure. When Driss falls ill, Georg finds a doctor named Richard (Godehard Giese), who is expected to set up a hospital abroad. But things become complicated when Georg discovers that Richard is living with Weidel’s wife Marie – the mysterious woman attracted to Georg – who will not depart with Richard because of Weidel, who she refuses to believe is dead, even when Georg tries (though not very hard) to tell her.

The insistent narration (Jean-Pierre Darroussin) begins in the freight train and the revelation of the story teller’s identity might lead to some head scratching. The effect of the narrator, who is alternatively unreliable and telling us what we are seeing, is distancing, and, competing as it is with the sub-titles and images, confusing. Paula Beer’s impressive breakthrough was the lead role in François Ozon’s film Frantz, but here her role, flitting between three men and unintentionally causing them all hardship and aggravation, is unsatisfying. It does not help that Rogowski (who was perfect as a petty criminal in the German film Victoria is, for all his altruism, an impenetrable character and one with little of Richard’s sex appeal.

Transit has the unreal quality of a dream, or a nightmare, and long before the jolting, but apt, Talking Heads song Road to Nowhere plays over the end credits, it seems that is where the characters, and our forgetful nations are heading.

You can watch the film trailer here: