Joyce Glasser reviews Rojo (September 6, 2019), Cert. 15, 109 min.

If some of the greatest American, British and French films owe their existence and strength to the two horrific world wars, Argentinean and Chilean cinema is haunted and inflamed by the right-wing dictatorships of Chile’s long Pinochet regime (1973-1990) and Argentina’s Dirty War (1976-1983). Both are marked by the many imprisoned and “disappeared” students, artists, and intellectuals and anyone resembling a socialist. These films include Argentine directors Héctor Babenco’s Oscar nominated 1985 Kiss of the Spider Woman (based on Manuel Puig’s 1976 novel); Juan José Campanella’s Academy Award winning The Secret in Their Eyes and Chilean Patricio Guzmán’s brilliant documentaries, beginning with the contemporaneous The Battle for Chile. In fiction, there are few trilogies as politically chilling as Pablo Larraín’s Tony Manero, Postmortem and NO.

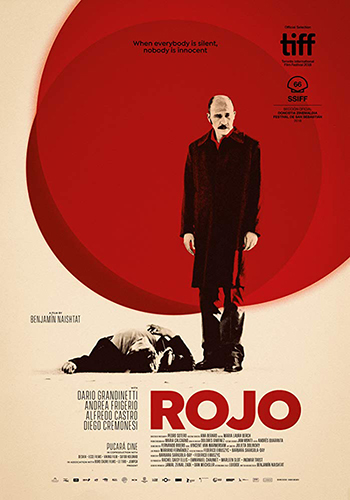

Now Benjamín Naishtat’s beguilingly innovative political thriller, Rojo (Red), set on the eve of Argentina’s US backed military junta’s 1976 coup d’état, is biding to join these masterworks. Naishtat’s connection is not only in the subject matter, but in the crew (his cinematographer, Pedro Sotero, shot Chile’s Kleber Mendonça Filho’s contemporary political dramas, Neighbouring Sounds and Aquarius) and cast. The film co-stars Darío Grandinetti, best known for his role in Argentine director Damian Szifron’s black comedy Wild Tales; and Alfredo Castro who stars or co-stars in Pablo Larraín’s trilogy, and in his more recent film, Neruda.

Now Benjamín Naishtat’s beguilingly innovative political thriller, Rojo (Red), set on the eve of Argentina’s US backed military junta’s 1976 coup d’état, is biding to join these masterworks. Naishtat’s connection is not only in the subject matter, but in the crew (his cinematographer, Pedro Sotero, shot Chile’s Kleber Mendonça Filho’s contemporary political dramas, Neighbouring Sounds and Aquarius) and cast. The film co-stars Darío Grandinetti, best known for his role in Argentine director Damian Szifron’s black comedy Wild Tales; and Alfredo Castro who stars or co-stars in Pablo Larraín’s trilogy, and in his more recent film, Neruda.

There have been many central characters who are charming villains or who have such a talent for evil that they become admirable. Or, like Tony Manero, protagonists who reflect the malevolent self-interest of the prevailing government. But in provincial counsellor and family man Claudio (Grandinetti) Naishtat is targeting the middle-class families bending the rules, and too complacent in their cocoons to recognise the corrosive effect of such corruption when they are part of it.

The story is set in 1975, on the eve of the coup, and the stench of the changing wind is in the air. It is no coincidence that when the brother-in-law of Claudio’s partner in a real-estate fraud, Vivas (Claudio Martínez Bel), is reported missing, Vivas hires Detective Sinclair (Castro) from Chile where the terror had already begun.

In an absurdist and surreal manner, the film opens on a suburban house that looks boarded up. Gradually, a well-dressed portly man emerges with a large clock, followed a few seconds later by a young woman with a pile of clothes under her arm, while later, two men exit with a television set. As there is no sign of a garage sale, this looks like orderly looting.

It might be a stylistic effect that Naishtat is going for, but one of the problems with Rojo is that each scene opens a door that is shut in the abrupt transition to the next scene and we fear we are losing the narrative thread. Some doors never reopen, but we will see this house again when Vivas approaches the respected counsellor Claudio with an illegal plan to purchase the seemingly abandoned property at the expense of an employed man who has petitioned Claudio for his severance cheque.

But before we hear about this house again, we meet the balding Claudio sitting in a popular restaurant waiting for his attractive, country-club set wife Susana (Andrea Frigerio). Suddenly a younger stranger (Diego Cremonesi) with a moustache to match Claudio’s, but a full head of hair, approaches, and begins to criticise Claudio for taking up a table just to read, when the man wants to eat. As the stranger’s argument grows louder, Claudio cedes his place, staring at the man as he studies the menu. Suddenly the man stands up yelling, “Son of a bitch, Nazis” and storming around the room until he is thrown out by a group of male diners.

In a significant line that is anything but throwaway, Claudio says out loud: ‘If my wife weren’t late all the time, this never would have happened.’ A foolish excuse that identifies Claudio as a shallow man always looking for the easy way out.

In arguably the most frightening scene in the film, the argument between the two men continues outside and ends with a suicide attempt, and a moaning body being dumped in the desert at sunset It is only at this point, a good ten minutes into the film, that the title is superimposed on the nocturnal sunset scene, with the o’s of Rojo forming two big eyes, as though to remind us that someone is always watching.

No South American or cine-literate viewer can watch this desert scene without thinking of Chile’s Atacama Desert where thousands of bodies were dumped for years after Pinochet’s 1973 coup, as documented in another Patricio Guzmán harrowing masterpiece, Nostalgia for the Light.

This restaurant sequence is the longest and more narratively coherent in the film. Much of what follows is a series of subplots most of which support this episode insofar as they are variations on the theme of disappearances. Claudio’s daughter Paula (Darío Grandinetti’s real life daughter Laura Grandinetti) takes part in a modern dance “play” in which she is abducted, literally carried away in the arms of a handsome fellow student dancer.

This scene is watched jealously by Paula’s sinister boyfriend, Santiago (Rafael Federman) who, is frustrated at her excuses for refusing to have intercourse. In one of the more heavy-handed subplots, Santiago conspires with his thuggish friends to abduct a curly haired musician who is friends with the male dancer. Even Santiago’s name suggests complicity with the incoming regime. He represents the younger generation that should be revolting, but instead becomes part of the problem.

In another scene Claudio and Susana watch a comedian-magician who choses a woman from the audience and makes her disappear. There is more subtlety and power in the climactic sequence in which Sinclair, a Columbo-type who is always showing up at Claudio’s office like a bad conscience, tells the relieved Claudio that he is returning to Santiago. But first he wants Claudio to drive him to the desert.

While a few of the scenes and subplots have no follow through, and serve to make a point that the writing is on the wall for Argentina, a seemingly gratuitous family holiday on the beach becomes deeply symbolic when Claudio squints at an eclipse while those watching with glasses warn him not to look. Claudio peaks, as though facing the future with willful blindness. The red of the eclipse and the title suggest the arrival of the anti-left and Peronist purge of the Alianza Anticomunista Argentina known as Triple A whose death squads rivalled those of Pinochet.

You can watch the film trailer here: