Joyce Glasser reviews Midnight Cowboy (September 13, 2019), Cert. 18, 113 min.

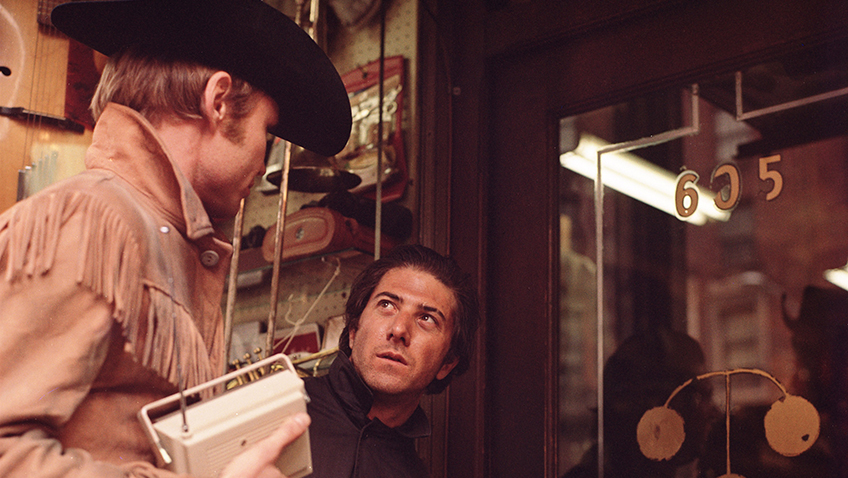

The 50th anniversary of John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy is being celebrated with a new 4K print restoration and a re-release to enable younger audiences to see the film on the big screen and older viewers to view this 1969 masterwork through different eyes. In his breakthrough performance, Jon Voight plays would-be hustler Joe Buck, who leaves his bad memories and dishwasher job in Texas for the lure of Manhattan only to end up in a condemned bedsit with Ratso Rizzo (Dustin Hoffman), a disabled swindler dying of TB and dreaming of Florida.

Joe’s long coach ride to New York is contrasted with the long coach ride that he will take at the end of the film when, like thousands of New Yorkers, he and Ratso head to Florida to escape the cold. What we experience in between is 1960s Manhattan before the onset of gentrification. Schlesinger, a former documentary filmmaker, recreates the feel and look of the period through the lenses of first-time cinematographer Adam Holender.

Joe is confident that, with his youthful good looks and tall, strong build; his fringed jacket and cowboy hat and boots, New York’s wealthy women will fall at his feet. His first conquest, forty-something socialite, Cass (Sylvia Miles), turns out to be a hustler, too, only she is a pro and ends up borrowing money from Joe for cab to her next rendezvous.

A chance encounter with greasy, lowlife, Rico ‘Ratso’ Rizzo (Hoffman) provides Joe with a ‘manager’ who promises to procure the women for a cut of the takings. Once again Joe finds himself conned, only now he is angry and tries to track down the limping, diminutive swindler to get his money back.

By the time he finds Ratso again, Joe, broke and homeless, has resorted to male prostitution. Schlesinger shot some of the film with a hidden camera so that many of the ‘extras’ you see film in the underground, on the streets, and at Times Square and 42nd Street are ordinary passersby. Eventually Joe makes eye contact with a nervous schoolboy, but Joe forgets to ask for the money up front and the boy cannot pay. He begs Joe not to tell his mother, and Joe spares him.

Ratso, who might have a bad conscience, or, like Joe, is just desperately lonely, offers the Texan a miserable chair in his squalid, icy squat. Joe and Ratso travel around the city together, stealing food. When Joe is invited to a Warholian party, Ratso tags along, but can barely make it up the stairs. While Ratso is stuffing his face and pockets with food, Joe is hallucinating on drugs and mesmerized by the cool, hip, artistic scene. He meets Shirley (Brenda Vaccaro – playing older, but in fact, a year younger than Voight), his first paying customer who, too late, is ready to hook him up with all her friends.

It was assistant director Michael Childers (who became a photographer and Schlesinger’s lifelong partner) who introduced the director to Andy Warhol and came up with the idea of the party in which Viva and other superstars from Warhol’s Factory took part. The party is one of the only indications that the swinging sixties were alive and well in NYC. All around Ratso’s squat the slums are being demolished and Ratso’s home, already stripped of plumping and heating, is next.

Quentin Tarantino’s latest film, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, is about a has-been TV Western star unable to adapt to the changing movie scene of 1969. Tarantino’s cowboy is the macho type of the old West and his stunt double does stunts, not tricks. Tarantino casts Brenda Vaccaro in a cameo as the wife of the actor’s manager (Al Pacino), who is nearly as sleazy as Ratso. This casting may be another way of reinforcing the idea that the 1969 Sharon Tate murders marked the end of an era; and that directors like Schlesinger, and actors like Hoffman and Pacino were replacing the old guard with ground-breaking films like Midnight Cowboy.

In addition to Ratso and Joe’s powerful, but never sentimentalised friendship, what everyone remembers is John Barry’s soundtrack. Nilsson’s chart-topping song, ‘Everybody’s Talkin’ surges with Joe’s spirits as he strides across his hometown to the bus station and Barry’s harmonica-driven instrumental Theme from Midnight Cowboy are as emotionally powerful as the performances are admirably restrained. Sadly, Bob Dylan’s Lay Lady Lay, which would have been the only missing piece of the 1960s in the film, was too late arriving to be used.

Joe’s mental flashbacks of his upbringing and youth are clumsy and too sketchy to tell a coherent story. The script, based on a 1965 novel by James Leo Herlihy, was already destined for an X rating for its references to homosexuality without adding more of his past. In the novel, Buck’s sordid upbringing, and his confusion about his sexuality are much more fleshed out. They are, in fact, reminiscent of the melodramatic flashbacks in the plays of Herlihy’s friend Tennessee Williams. Schlesinger, however, wanted to focus on the present friendship between the two lonely men.

Although Hoffman had shot to fame two years earlier with The Graduate, his performance in that film was so convincing that Schlesinger needed to be convinced that Hoffman, though older than his character in Herlihy’s novel, could play the opposite of a naïve, squeaky-clean student. Hoffman did so and went on to become one of the greatest character actors of all time.

Midnight Cowboy won the Academy Award for Best Picture and Director, but though nominated, both left empty handed. Hoffman later teamed up with Schlesinger in the hit 1974 thriller, Marathon Man, but had to wait until 1980 to win his first Academy Award (Kramer vs Kramer). Midnight Cowboy

also won the Best Adapted Screenplay Award for Waldo Salt’s script, and nine years later both Salt and Voight won Oscars for Coming Home.

BFI Distribution celebrates the 50th Anniversary of Midnight Cowboy with a new digital 4K restoration. In cinemas 13 September 2019.

You can watch the film trailer here: