Joyce Glasser reviews Free State of Jones (September 30, 2016) Cert. 15, 140 min.

The Free State of Jones is an ambitious historical saga based on two books and the controversial life of Newton Knight (played with bravura by Matthew McConaughey) — the anti-slavery blacksmith who turned Jones county, Mississippi into a tiny rebel republic during the American Civil War. Knight is not a household name in the USA let alone in the UK but five-time Academy Award nominated writer/director Gary Ross (The Hunger Games, Pleasantville) recognises a great story when he sees one. The mystery is why he couldn’t see the drama spreading thin as he ploughs through American history, gathering issues, characters and stories much like Newton Knight gathered the outcasts of the dying Confederate cause.

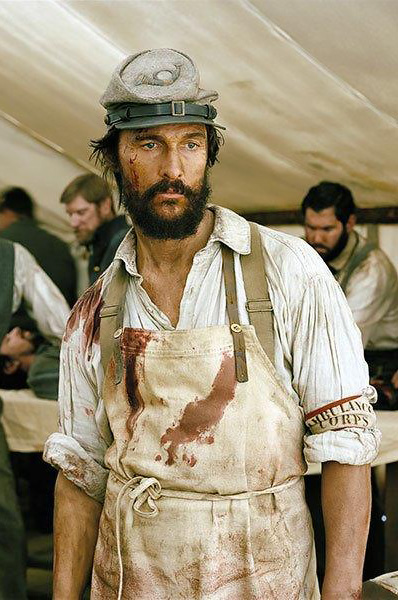

The film begins at the Battle of Corinth in 1862 with Newton Knight (McConaughey) dragging bodies off the battlefield. He complains to his comrades about the 20 Slave Rule that allows landowners who own 20 slaves to remain on their plantations while two sons are exempt if the family owns 40 slaves. “I’m tired of helpin’ ’em fight for their damn cotton,” he declares defiantly. When Knight watches his newly-conscripted ‘kin’, an under-aged neighbour or relative from back home, die on his first day of battle, he decides to give the boy a proper home burial.

Fully aware of the punishment for desertion, Newton returns to his farm in Jones County where he finds his wife Serena (Keri Russell) barely surviving with a young baby who is on death’s door. Friends recommend a black house slave named Rachel (Gugu Mbatha-Raw) who cures the baby. While there Newton witnesses confederate soldiers looting neighbouring farms and, outraged, makes a decision that will change his life forever.

Badly wounded escaping from the soldiers, and with the help of friends from the local tavern, Newton is taken to a camp in the middle of a densely wooded bayou. There, he finds himself with a small group of runaway slaves and is cured by none other than Rachel, who risks her life sneaking out of the plantation at night. The men are relatively safe from large attacks in the swamp as Calvary horses, wagons and canon cannot enter.

Newton is soon accepted by the others and strikes up a friendship with Moses (Mahershala Ali), who still wears an iron collar – that resembles an upside down chair — around his neck. In time, the numbers in the camp swell to include impoverished, besieged farmers, draft dodgers, widows and children and large numbers of deserters following the defeat at the Siege of Vicksburg in 1863.

This should be the nucleus of the film as Newton plays Robin Hood to a rainbow band of merry (and less merry) rebels, cowards and strong minded individuals taking a moral stance. In one exciting scene, Newton, who announces he was a blacksmith before the war (who’s to know?) decides to liberate Moses from the harness around his neck. Aware that the noise of the saw will attract foot soldiers, the men are prepared with a stolen shipment of rifles. But aside from that, and Newton helping Rachel with her reading, life in the camp never comes to life. There is one incident in which, after a feast on pigs and corn salvaged from the marauding soldiers, a white farmer insults Moses with a racist threat. The incident is not really resolved but makes you long to know more about how this interracial camp functioned on a day-to-day basis.

Eventually the camp is large enough to enable the rebels to leave the bayou and go on the offensive, triumphing over the army with guerrilla tactics. Gradually Newton and his men take over three counties and make contact with the Union Army for support. With the swelling numbers, however, come leadership struggles (glossed over), and then, the news that the war is over.

If the film ended there, it might have made an uplifting and entertaining if controversial story about an early Civil Rights hero, but it does not. Like the mini-series it might have been, Ross goes on to show the sobering reality behind the emancipation of the slaves including unlawful barriers to the newly-granted black vote and the emergence of the Klu Klux Klan. Newton’s family life is glossed over to the point of confusion. He has now married to pregnant Rachel and Serena (who left the county for her and her child’s safety) returns at the end of the war and lives with them. Not mentioned in the film, though, are Newton’s seven other children from both women. When the new union government withdraws troops from the area, lawlessness envelopes the South.

But it doesn’t even end there. Just over half way through the story, we meet, in jarring flash forwards that are differentiated from the main timeline by style and palette, Newton’s great-great-great grandson. He and his white fiancée are paying for the ‘sins’ of his ancestor thanks to Mississippi’s miscegenation laws.

McConaughey, who won an Academy Award for the Dallas Buyers Club, is suitably hirsute and grungy in a good physical reimagining of the real Newton Knight, but Knight never becomes real, let alone charismatic. Knight remains an enigma, perhaps because Ross does not want to romanticise his character any more than he has to. It is not however, the performances that are the problem. Ross, the talented co-writer of Tom Hanks’ Big and the Academy Award nominated Seabiscuit, loses control of a script that never finds its dramatic focus.

You can watch the film trailer here: