Joyce Glasser reviews Dark River (February 23, 2018) Cert 15, 89 min.

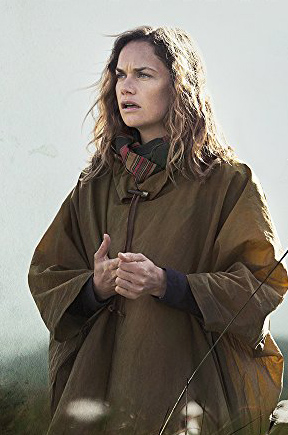

Writer/director Clio Barnard’s Dark River returns us to her Yorkshire homeland that was so viscerally and powerfully visualised in The Selfish Giant and The Arbor. With so much farmland mud around in the film, you might think that the title refers to contamination, as in Simon Beaufoy’s hoof and mouth farm story, The Darkest Light. While the darkness might be metaphorical, there is no shortage of problems on the Bell family’s farm when estranged sister Alice (Ruth Wilson), returns after 15 years of shearing sheep on other people’s farms. You can’t fault the performances in this modern Greek tragedy but after The Levelling and God’s Own Country, this heavy dose of Yorkshire misery might leave you crying mercy!

Rather surprisingly, since Alice is in her mid-thirties, and is uncommonly attractive and hardworking, she has not married a farmer or anyone else during the 15 years she was away doing contract work. Instead, she decides to return home to her family’s small sheep farm as the news that her father has died leads her to believe she has some title to the farm.

The rivalry of siblings with claims to a single father’s (here, Sean Bean – glimpsed in short hazy flashbacks) farm; the return of the estranged daughter to find a farm in dire straits; the necessity to sell some of the herd and even the daughter witnessing the mercy killing of a helpless animal beyond saving, are events that also feature in The Levelling, another film from a female director, albeit shot in Somerset not Yorkshire. If Alice is spared The Levelling’s bovine TB, badger culling and a mysterious suicide, she has her own demons to face.

Alice’s gloomy older brother Joe (Mark Stanley from ‘Game of Thrones’) has a good idea of what chased Alice away. If he feels guilty, he is unable to explain why he did not intervene to save her. He certainly does not feel he owes Alice anything now and they quarrel bitterly about how the farm should be run. In one strong scene, Alice tries to take control by selling some sheep to pay an extra farm hand against Joe’s advice. She fails to get the price she needs and angrily shuns the patronising offer of a creepy friend of her father to do the work for a lower price.

Joe is so burnt out, angry and disillusioned that Alice comes across as the more determined, competent and credible of the siblings when the freeholder comes around to inspect. She promises that she will make things right after he threatens not to renew the lease due to Joe’s negligent management.

But such is Joe’s anger at having been left to run the farm by himself while caring for their sick father for 15 years that he prefers to sign away the farm to developers behind Alice’s back than let her try to preserve it on her own terms.

All of this is very dramatic except that Barnard’s insistence on showing us the unromantic side of farm life is almost a parody of the genre. In God’s Own Country the two farmhand lovers were always putting their arms up sheep rectums to drag out babies, but a scene in which Alice skins and chops up a bloody rabbit in relentless close-up shots seems more like punishment than story telling.

This insistence in showing us how ugly and brutal life on the farm really is extends to the décor. If you wondered how anyone could live in the farmhouse in The Levelling, it is luxurious compared to the derelict, filthy, pigsty of a farmhouse in Dark River. Oh, how production designer Helen Scot, Art Decorator Laura Hardy and Set Decorator Maxine Carlier must have had fun seeing how disgusting they could make the house, from the mice, rats and dirty dishes piled high in the sink to the ripped, mouldy furniture. And Alice does not even live in the main farmhouse, but in a claustrophobic annex on the other end of it.

Films about the miserable life of farm families are nothing new, of course, and it’s still hard to rival the sufferings of Tom Joad’s after his return to his family’s failing farm in The Grapes of Wrath. But here the determination to make city dwellers and second homeowners squirm risks becoming the story in itself. The endless mud, the rusty taps with no water, the broken sheds and unappetising menus are so self-consciously evoked that we are almost distracted from the historic child abuse story that is, in any event, too remote for us to relate to emotionally.

You can watch the film trailer here: