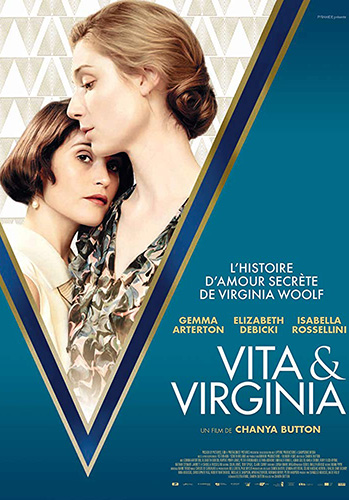

Joyce Glasser reviews Vita & Virginia (July 5, 2019), Cert. 12A, 110 min.

Vita & Virginia is another chapter in the seemingly fathomless anthology of scandalous stories from the Bloomsbury Group. It is distinguished by being based on the revealing stage play by Eileen Atkins; by co-starring the talented Elizabeth Debicki, who delivers the most credible interpretation of Virginia Woolf on film; and by being the second feature co-written (Eileen Atkins gets co-writer credit) and directed by Chanya Button. Button’s 2015 film, Burn, Burn, Burn, inspired by the macho road trip, On the Road, but with female actors, heralded the arrival of a feminist filmmaker out to make films about women.

Despite the titillating prospect of two famous, English women, each married to high profile men, falling in love and sleeping together (there’s a 12A rating, so it’s not all that titillating) the lack of drama, and the expository and epistolary nature of the narrative might limit the film’s appeal.

Despite the titillating prospect of two famous, English women, each married to high profile men, falling in love and sleeping together (there’s a 12A rating, so it’s not all that titillating) the lack of drama, and the expository and epistolary nature of the narrative might limit the film’s appeal.

The famous women are Vita Sackville West (Gemma Arterton, Quantum of Solace, Tamara Drewe) and Virginia Woolf (Elizabeth Debicki, Widows, The Great Gatsby). You can Vita’s famous gardens in Sissinghurst, Kent, and some of the books of Virginia Woolf are on the school curriculum. The high profile film, The Hours and Tilda Swinton’s breakthrough film, Orlando, and many programmes about the Bloomsbury Group have further elevated her name and renown.

Many of us have visited Charleston Farmhouse in Sussex where several scenes in the film seem to take place. Charleston was the country home where, in 1916, Virginia’s sister, Vanessa (Emerald Fennell), a painter, set up house with Duncan Grant (Adam Gillen), with whom she had a daughter, Angelica; Grant’s lover David Garnett and her husband Clive Bell (Gethin Anthony), who was by now with someone else.

These colourful artistic types who decorated Charleston with arts and crafts; Virginia’s writer/publisher husband Leonard (whose Hogarth Press published the first edition of The Waste Land) and Vita’s husband Sir Harold Nicolson (Rupert Penry-Jones), a heterosexual diplomat, author and politician – are all interesting people in their own right. Here, they get a quick look in, just enough for some base-covering and name-dropping, but not enough for any meaningful characterisations.

The play dispensed with all this entourage by being a two-hander telling the love story through the revealing letters of the two women as they were apart more than together over a period of ten years.

The letters here only serve to freeze the drama as their purpose is emotional, not dramatic, and they are difficult to digest out of context. Far from pulling us into the story, they tend to remove us from it.

Buttons does try hard to pull us in. There is a pulsating electronic score by Isobel Waller-Bridge (‘Fleabag’ Phoebe’s sister) that sometimes is just what the doctor ordered, but other times, just keeps you awake. Button uses special effects – a murder of crows consume Virginia while vegetation sets in to eat away at the rest of her – in expressionistic scenes to suggest Woolf’s mental fragility. And then there is Debicki’s performance, aided by her height and aristocratic, make-free face and dour attire. Virginia carries her gangly body with an awkwardness that is like a hesitation before each step or like an apology for moving. She swallows her words which you can almost see being pulled through her long neck while her eyes dart around taking everything in like radar.

And Buttons does impart a definite take on the evolution of the relationship. Arterton, who also produces the film, portrays Vita as a bubbly, flamboyant, spoilt predator (Nicolson’s famous tirade against her lover, Violet Trefusis, with whom Vita eloped in a national scandal, is recreated here). She is the complete opposite of Virginia. Isabella Rossellini’s brief appearance as Vita’s mother represents the wall of class and tradition against which Vita hurls herself like a wilful child. Lady Sackville is appalled that Vita would mingle with ‘socialists’ and, though not mentioned, it did not help that Leonard Woolf is a Jew.

But Vita is desperate to meet the female literary sensation she has heard about and crashes a party to do just that. Vita might have been fascinated by Virginia’s mind, but here it seems she is more intrigued by the well-earned literary fame that eluded her.

Virginia is a trophy for Vita. Woolf is uncomfortable with sex in general, but she is somehow, seduced by Vita. It’s hard to figure out why. Perhaps it is her sexual awakening, or perhaps their dalliances (hardly seen in the film) remind her of her more carefree youth when she was involved in such escapades as the Dreadnaught Hoax. When Vita tires of Virginia, Virginia tries to win her back with Orlando. The relationship evolves into that of writer and muse but this change of calibre is sketchily dramatised.

If this had been the focus of the film from the outset, the posterial impact of the relationship might have given the film its direction. For the novelist, this strong-willed gender changing woman from a wealthy landowning dynasty is the raw material of a novel in which her imagination can make of Vita what she wanted. Virginia did not think much of Vita’s writing, but she thanked her muse and lover by immortalising her in one of the 20th Century’s most revolutionary novels.

You can watch the film trailer here: