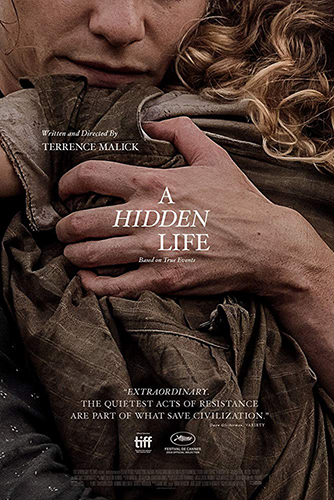

Joyce Glasser reviews A Hidden Life (January 17, 2020), Cert. 12A 174 min.

With A Hidden Life, Terrence Malick returns to form after exasperating his fan base with To the Wonder and Knight of Cups; visually striking, but self-indulgent, cryptic and rambling films with no discernible script, relatable characters or narrative drive. A Hidden Life could not be more different. The film is not only based on a true story set in Austria and Germany between 1939 and 1943, but captions helpfully situate us geographically and temporally.

Those looking back on the Texas-born director’s early masterpieces, Badlands (93 minutes) and Days of Heaven (94 minutes), might nonetheless find the term, “return to form” greatly exaggerated: A Hidden Life is, after all, no more complex than these two films and nearly twice as long. But if ever a story needs that time – the time for us to see the seasons changing; a loving couple dreaming in each other’s arms; the clouds sweeping over the mountains and children growing – it is this ambitious saga that tracks the evolution of a man’s spiritual resolve.

Those looking back on the Texas-born director’s early masterpieces, Badlands (93 minutes) and Days of Heaven (94 minutes), might nonetheless find the term, “return to form” greatly exaggerated: A Hidden Life is, after all, no more complex than these two films and nearly twice as long. But if ever a story needs that time – the time for us to see the seasons changing; a loving couple dreaming in each other’s arms; the clouds sweeping over the mountains and children growing – it is this ambitious saga that tracks the evolution of a man’s spiritual resolve.

The man is young, handsome, peasant farmer, husband and father Franz Jägerstätter (August Diehl), born, married and, when the film opens in 1939, hard at work with his loving wife Fani (Valerie Pachner), in the Alpine village of St Radegund, Austria. Throughout the film the two take turns narrating their feelings of love and happiness and then despair. But in 1939, Franz and Fani are a golden couple, popular and respected with a growing family of beautiful daughters. Franz’s elderly mother and later, Fani’s sister Resie (Maria Simon) come to live with them and the days pass with love, hard work and laughter.

The attitude of the community begins to change when Franz’s views of the war become known as he leaves his family to complete basic training in 1940. Franz and Fani communicate by letters which the respective actors read out loud off camera. “We could use you here to break in the calf,” Fani writes, as though expressing her fears in a dream. He writes, “Oh my wife, what’s happening to our country; the land I love?” After France surrenders, Franz returns to his family with the cadence of life attuned once again to the changing seasons and the elements.

Karl Markovics in A Hidden Life

But there is no peace and now we see Nazi’s walking through the village. Franz is reprimanded by the community for refusing to donate money to the war effort, although he also refuses to accept the family allowance. “Nobody refused but you”, a man says, the first overt sign that Franz will follow a different drummer. The mayor (Karl Markovics) condemns Franz. “You are worse than them. They are the enemy; you are a traitor”.

When Franz, a conscientious objector, is called up to fight, he battles with his conscious for Austrian men must sign an oath of allegiance to Hitler. All the Parish priest can do is to tell Franz that his sacrifice on principle will benefit no one. And, after all, even if he signs, God will know what is really in his heart.

Dressed in his Sunday best, Franz goes to see Bishop Joseph Fliesser (Michael Nyqvist), ensconced in his sumptuous office. The Bishop is a collaborator, perhaps to save his skin, and wants Franz to compromise to save his. He quotes the Apostle, that every man be subject to the powers over him and tells Franz he has a duty to the Fatherland. “If God gives us free will,” Franz reasons, “we are responsible for what we do. If our rulers are evil. What do we do?” This question is as relevant today as it was then. Franz concludes, “I want to save my life, but not through lies.”

Franz is offered non-combatant duties, but still refuses to say an oath of allegiance leaving his fate to God. When he is arrested, life becomes intolerable for Fani as the villagers turn against her. She writes to Franz: “I hear nothing but your voice.” Unlike Malick’s 1998 war film, The Thin Red Line, the conflict does not take place on the battlefield, but in the troubled, but constant mind of a husband and loving father.

While a form of narration by whispering disembodied voices, prevalent in Malick’s films of the last decade, continues here, it is supplemented by sparse, coherent, and often lyrical dialogue. As always with Malick the gorgeous, lingering images of the natural world and montages of the family at work and at play make any more dialogue than this unnecessary.

But at 76, Malick is proving more flexible than his protagonist. Perhaps as a concession to the budget for filming in Europe, or to increase the authenticity of our immersive experience, Malick’s regular cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki has been replaced by Lubezki’s German camera operator, Jörg Widmer, who makes us believe in Franz’s communion with the natural world. German production designer Sebastian T. Krawinkel helps tell the story through the contrasts between the Franz’s humble wooden farmhouse and the Nazi offices; between the frescoed local Church and the Bishop’s overpowering Baroque Church and between the green, wild-flower studded mountains and the squalid jail cells of Tegel prison in Berlin. German costume designer Lisy Christl’s apparel is so real that even when Franz and Fani speak bits of English, we hear authentic South Tyrol voices. James Newton Howard’s unobtrusive score is appropriately dominated by Eastern European classical musical of the Romantic period.

August Diehl and Valerie Pachner in A Hidden Life

Franz’s journey from the paradise of St Radegund to a guillotine in Berlin is characterised not by length, but by the depth of his meditation, and the strength Franz takes from his love for Fani, nature and God, as opposed to organised religion. In a powerful scene in Berlin, the judge (Bruno Ganz, who died of cancer last February) tries to convince Franz to save his own life, but ends up watching him in awe, like the Romans watched Christ looking upward to accept his fate.

While Diehl’s powerful performance dominates the film, perhaps the strongest character is Fani, who is spurned by the villagers when Franz refuses to fight and will be left to do the heavy farm work and bring up three young girls on her own. While she alone has the power to persuade Franz to live for her sake, she remains silent, respecting the decision he must make alone.

Throughout the film the various authorities tell Fani and Franz that their sacrifice will change nothing, and Franz will be forgotten. It is therefore fitting that Malick ends his emotionally charged film with a quote from George Elliot: “But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.”

You can watch the film trailer here: