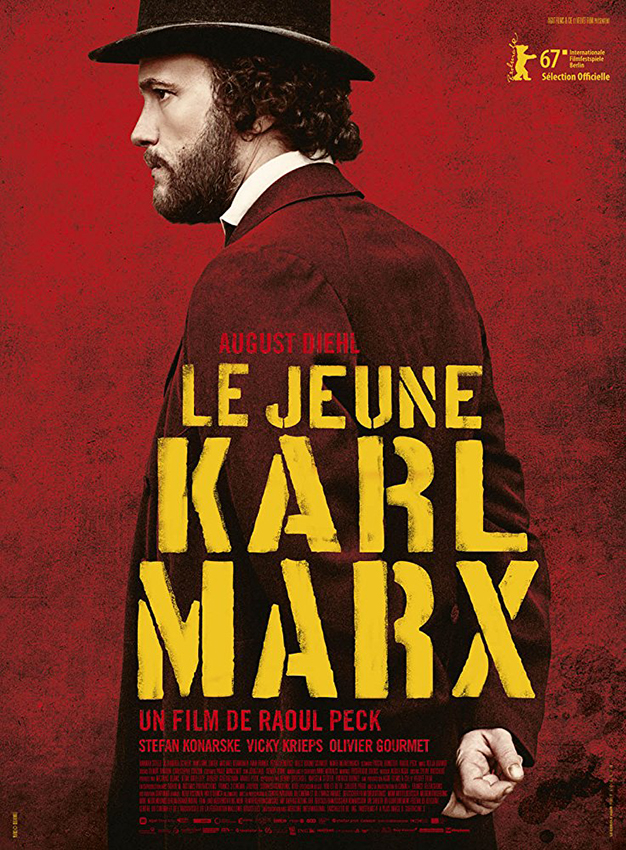

Joyce Glasser reviews The Young Karl Marx (Le jeune Karl Marx) (May 4, 2018) Cert TBC, 188 min.

After Raoul Peck’s powerful and thought-provoking documentary, I Am Not Your Negro about the writer James Baldwin, it is, at first, a surprise to find Raoul Peck behind this informative, historically accurate, but dramatically lacking biopic of Karl Marx’s journey from an middle-class student/intellectual and law graduate in Prussia, to a family man and stateless political activist longing to write Das Kapital. It is only when Bob Dylan’s Like a Rolling Stone thunders out over archival footage of the civil rights movement that we establish the connection. Intellectually, and biographically, it is more comprehensive and satisfying than the farcical Young Marx that recently ran at London’s new Bridge Theatre, but it lacks the introspection that made I Am Not Your Negro so profound, and a modern perspective.

The film begins when Marx (August Diehl) has been exiled from Prussia and is living in exile in Paris in 1843. With him is Jenny von Westphalen (Vicky Krieps) the daughter of an aristocratic family in Marx’s home town of Trier, who gave up her life of luxury and security for ‘the son of a converted Jew.’ She lived largely on the money orders from Friedrich Engels (Stefan Konarske) in cramped apartments in Paris, Brussels, Cologne and London giving Marx seven babies (two of whom, the boys, died before the age of 9). The close relationship between Jenny, a childhood friend of Karl who was also well-educated and Marx is well portrayed, as is her continual belief in the importance of his work. She is realistic however, when she jokingly tells Engels that the three of them are not enough to change the world; they will need a few more supporters.

The film begins when Marx (August Diehl) has been exiled from Prussia and is living in exile in Paris in 1843. With him is Jenny von Westphalen (Vicky Krieps) the daughter of an aristocratic family in Marx’s home town of Trier, who gave up her life of luxury and security for ‘the son of a converted Jew.’ She lived largely on the money orders from Friedrich Engels (Stefan Konarske) in cramped apartments in Paris, Brussels, Cologne and London giving Marx seven babies (two of whom, the boys, died before the age of 9). The close relationship between Jenny, a childhood friend of Karl who was also well-educated and Marx is well portrayed, as is her continual belief in the importance of his work. She is realistic however, when she jokingly tells Engels that the three of them are not enough to change the world; they will need a few more supporters.

Admirably, in terms of authenticity, Marx speaks to the beloved French libertarian socialist and journalist Pierre Proudhon (Olivier Gourmet) in French, and Engels, the rebellious son of a wealthy Manchester factory owner, speaks to his future wife, the pretty, spirited, Scottish factory worker Mary Burns (Hannah Steele) in English. Engels, who is German, speaks to his close friend Marx in German. Just why Jenny and Karl speak to one another in French at times, is curious.

Far from dumbing down, Peck attempts to dramatise the divide between the various groups and individuals with whom Marx comes into contact. When Marx discovers that Arnold Ruge (Hans-Uwe Bauer), a journalist and philosopher with whom he briefly edited a paper, owns shares in a railway, he confronts Ruge about the back pay due to him. Engels is in the room and, according to the film, the two (who had previously) are ‘re-introduced.’ At first they are suspicious of one another and at loggerheads, and then, within minutes, a mutual admiration society is formed.

Peck paints a convincing portrait of the mutual interdependence between the two idealists. Ruge returns to pay Marx his fee with the excuse, ‘that the share price decreased,’ but, by then Engels and Marx have started a long drinking/chess session. After bonding over a night of discussion (Engels encourages Marx to read the key economical writers) Engels becomes the first friend Marx ever invited home. Ruge never shared Marx’s socialist theories, but followed Marx in exile to Paris and then to the UK (where he died in Brighton).

Peck also explores Marx’s relationship with Pierre Proudhon. ‘I think there are two men in you’, he tells the older, respected journalist and philosopher. ‘The critical Proudhon thinking in abstract categories, and the real Proudhon who see real poverty.’ The film does not however, catch the irony of this audacious comment for Proudhon was born into poverty and Marx was born and raised in a bourgeois family. Later Marx acknowledge to a group of workers that Proudhon is a great man, but not a great economist.’ The weakness is that he ‘dreams of improving a system that naturally produces poverty, not of transforming it.’

But while Peck attempts to shine a light on the major stages in Marx’s development as a political thinker, the characters Guizot and Grün remain just names and the running joke of Marx’s proposed book, A Critique of Critical Critique will be lost on many Similarly Marx’s hostility to a rival young Hegelian, Bruno Bauer is never explained, nor his attempt to formulate a materialistic conception of history. In fact, Marx’s book, On the Jewish Question, published in Ruge’s paper, but not mentioned in the film, challenges Bauer’s claim that Jews cannot achieve political emancipation unless they disassociate themselves from their religion. Similarly, Marx’s triumph over an initially hostile The League of the Just in London is nicely done, but we never never hear more about the League.

There is a scene in England in which Engels, with Mary, Jenny and Marx, bumps into a friend of his father, and a fellow factory owner. Marx tells him he is researching child labour and the factory owner defends it, telling Marx with all sincerity that ‘if labour costs more, they’d be no more profits and no more society.’ When Marx tells him, ‘we’re not speaking the same language; what you call profit, I call exploitation,’ he makes it clear he is not doing research but closing all dialogue.

More subtle and natural are the conversations between Engels and Marx about deadlines and Marx’s claim to be exhausted, at 30, from political activism and writing pamphlets. Peck romanticises the hammering out of The Communist Manifesto in 1948 and a caption informs us that revolution broke out a month after. If the old regime was overthrown in Western Europe and ‘the international workers union arose from the ruins’, it was not to last. It would be another 67 years before the 1917 Russian revolution, which is the one most associated in our minds with The Communist Manifesto

and Das Kapital

, the book that was to preoccupy Marx in London until his death in 1883.

Diehl, best known in the UK for his role as Dieter Hellstrom in Inglourious Basterds and the lead in the 2007 Oscar-winning The Counterfeiters, makes an affable Marx, but fails to add sufficient depth and nuance to this role. While we see how Engels struggles with the hypocrisy of his situation, Marx, who, who never did much physical labour and remains an uncomfortable bourgeois, writes in The Communist Manifesto of a class war between the middle and the working class. But it is up to the director to give the biopic an historical perspective. It is impossible not to be thinking of how quickly Marx’s theories and idealism turned to barbarism. Stalin’s reign of terror was one long 1905 Bloody Sunday when the Tsar was still in power. Under Putin, there is a huge divide between rich and poor but under state sanctioned corruption and political oppression.

You can watch the film trailer here: