Joyce Glasser reviews McCullin (January 1, 2013), Cert. 15, 93 min.

Don McCullin, the first photojournalist to receive a CBE (in 1993), was born and raised in the tenements of Finsbury Park in 1935 and believes, ‘it was a miracle I escaped Finsbury Park’. He experienced war early on as a child in WWII and left school at 15 to work when his father died, putting an end to his dream of going to art school. After spending his National Service in the Suez Canal Zone, working in the darkroom, he returned to Finsbury Park and began taking photos of a different kind of warfare. When, in 1959, the Observer published what became an iconic photo of the Guvners, a notorious local gang accused of murdering a policeman, his career was launched.

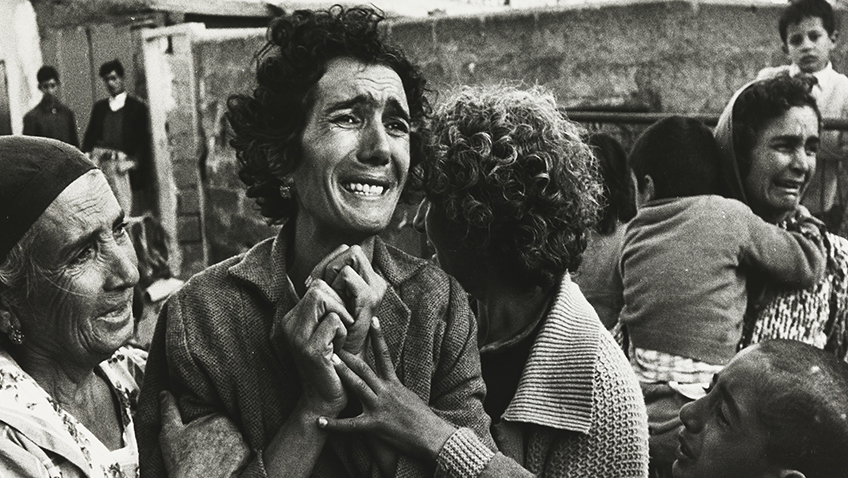

That long career, which was to take him to war zones throughout the world for over 20 years, is the subject of this revealing and fascinating documentary by David Morris and Jacqui Morris. It is lucidly and candidly narrated by Don McCullin himself and illustrated with examples of his brilliant photos and video footage. Some of these photos are difficult to stomach, but that’s the point.

It was while he was working locally for the Observer in 1964 that McCullin received his ‘baptism of war’ when he was sent to cover the civil war in Cyprus. In addition to learning to ‘assess where the bullets were coming from’, he says that he was ‘learning about the price of humanity.’ He was a fast learner and after four-and-a-half-years had outgrown his job at the Observer.

Through his friend, David King, the Sunday Times Art Director, McCullin landed a contract with the Sunday Times Magazine for which he did his finest work. His success was due to a combination of his great eye and, his equally important talent for being in the right place and the right time. ‘The 60s were packed with opportunities if you wanted to go to war,’ he recalls, and at the time, there were no restrictions on what he could cover and how. Moreover, the Sunday Times was at the time at the forefront of investigative journalism.

McCullin took full advantage of this freedom, which is denied to photojournalists today. He also took great risks and showed incredible initiative to get his pictures. One of the most compelling segments of the film is his account of him pretending to be a mercenary during the war of independence in the Belgium Congo in order to leave Leopoldville for the rural killing fields. Of the mercenary leader, Mike Hoare, he comments, ‘there was goodness in Mike Hoare, but not much goodness in what he stood for. He was in it for the adventure and money…Some of these mercenaries had a lust for killing Africans. I hated them in the end.’ We are shown why.

In addition to Cyprus and the Congo, the documentary illustrates McCullin’s coverage of Vietnam (he went three times); Cambodia, the 1967 war in Israel, BIAFRA, Bangladesh, the Lebanese War, Northern Ireland, and the Russian invasion of Afghanistan. McCullin’s instinct for sensing a story is demonstrated by a revealing anecdote about how he managed to cover the very rapid building of the Berlin Wall.

McCullin reminds us that under Editor-in-Chief Harold Evans (1967-1981), the Sunday Times, with its world famous Insights Team, was a world leader in investigative, independent and critical journalism. When in 1980 and 1981, the unions made it impossible for the paper’s owner, Kenneth Thompson, son of the Canadian media mogul, Baron Thompson of Fleet, to survive, Thompson sold the paper to Rupert Murdoch. Evans was an early casualty and by 1982, McCullin was out. When he wasn’t sent to cover the Falklands, he initially suspected censorship, but it turned out to be bureaucracy.

Instead of becoming hardened and cynical during his exposure to war, McCullin continued to feel deeply and reflect on the human condition. ‘Even my dark room is a haunted place,’ he says. ‘I don’t just take photographs, I think.’ He talks about his conscience, and admits that in danger zones he intervened to help victims whenever he could. His photos are marked not only by the spontaneous drama of the moment, but by a deep humanism. Behind the image there is a feeling of human suffering and emotion.

Perhaps because of his background, McCullin’s sympathies lay with the poor and dispossessed, as well as with the young soldiers slaughtered in hopeless, pointless wars like Vietnam. His painfully real shots of the dying American troops certainly contributed to the strong anti-war movement that eventually ended the War.

McCullin has no time for embedded journalists but ironically, it was probably his photos more than anyone’s that led to the advent of embedding and to restrictions on the freedom of photojournalists.

‘You have to bear witness,’ he says matter of factly. The must-see documentary McCullin bears witness to how this incredible man went about doing just that for 20 turbulent years.

You can watch the film trailer here: