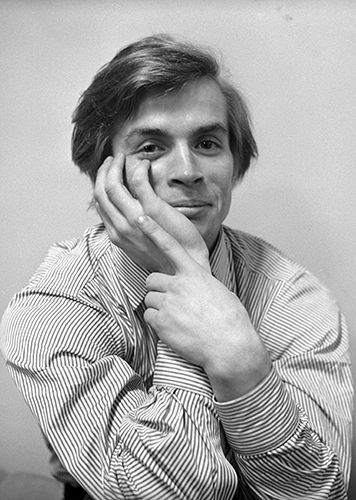

Joyce Glasser reviews Nureyev (September 25, 2018), Cert. 12A, 109 min.

Brother and sister team Jacqui Morris and David Morris, who previously collaborated on the excellent documentary (McCullin) about war photographer Don McCullin now present a cradle-to-grave documentary about the great Russian/French ballet dancer/choreographer/artistic director, Rudolph Nureyev. Their film includes previously unseen ‘amateur’ footage of his little known modern dance work and specifically his work with Martha Graham whom he greatly admired.

There have been other documentaries and films about – and starring – Nureyev, from Ken Russell’s Valentino starring Nureyev to the BBC’s excellent, Rudolf Nureyev: Dance to Freedom and more specific documentaries such as Fonteyn and Nureyev – The Perfect Partnership (1985) and PBS’s Nureyev: The Russian Years. Anyone over 60 will have born witness to his dramatic defection in Paris and might have seen him dance in London with Margot Fonteyn or elsewhere. The documentary’s most generous clip is of the Fonteyn/Nureyev Romeo and Juliet, which is arguably their greatest collaboration (fortunately recorded).

Rudolf Nureyev, an only son with three old sisters, was born on a train travelling near Irkutsk, Siberia, bound for Vladivostok, where his father, a Red Army political commissar, was stationed. So you could say that movement was his birthright. He was a Tatar Muslim and on his death chose to be buried in the Russian cemetery outside of Paris rather than in the celebrity-filled Paris cemetery of Père Lachaise.

The film covers his discovery of dance; his participation in local folk dances; his local training and his decision to attend the Mariinsky Ballet School in St Petersburg rather than the Bolshoi. We see him, early on, dazzling Soviet crowds and leaders. We learn about his defection in Paris and the famous partnership with The Royal Ballet’s lauded prima ballerina Margot Fonteyn.

She was 42 and committed to another dancer when Nureyev, 23, arrived in London, insisting that he dance with her or no one. (Nureyev would have been comfortable with an older ballerina: his partner for three years at the Mariinsky, Ninel Kurgapkina, was a decade older than him). What is absent from the film’s narrative is that Nureyev had a test in London. Sir Frederick Ashton, reluctant to choreograph for a dancer he did not know, was asked to create a short ballet for him to perform at Fonteyn’s charity gala. It was such a success that the company engaged him and Fonteyn became his partner.

The film also covers his long creative and sexual relationship with Danish ballet dancer, choreographer – and Nureyev’s biggest competitor – Erik Bruhn (1928-1986), ten years his senior. This relationship and Fonteyn’s are the most jumbled, perhaps because they take place over time. Just when we are getting into a strand, we are taken elsewhere and suddenly Fonteyn is dead, and suddenly Bruhn returns when we thought he was out of the picture. The later years of Nureyev’s life and his work turning the Paris Ballet (Culture Minister Jacques Lang offered him the position in 1983) into a leading company are also covered, albeit superficially.

While the directors supply a continual stream of wonderful archival footage (though the segments are very short), what they had in McCullin that is missing here is Nureyev himself. Even if they cannot revive the dead, they could have told his story a lot better. The depiction of his defection is bland compared with the average newspaper account and drama is again missing in the aftermath: the disappointment of the ROH when the Mariinsky Ballet arrived without the anticipated star Nureyev who had been such a sensation in Paris.

Perhaps at 94, Sir John Tooley is unable to be interviewed, but his written recollection of the period when Nureyev finally made it to the ROH is riveting and revealing. Tooley offered Nureyev the role of Artistic Director of the Royal Ballet, despite knowing how critical he was about the amount of mime use; the type of dancing and despite his reputation. Nureyev refused the job when he was told that his performances would be reduced in line with his considerable new role and duties.

Thankfully, for it meant that he performed as often as he could before the onset of Aids and age-related factors slowed him down. And then, he could take smaller roles in longer operas. He would assign the major roles to young dancers to keep them in the Paris Ballet and to develop their skills in the company repertoire that he greatly expanded. The documentary does mention the less physically demanding or shorter parts created specifically for him: the Overcoat and Death in Venice.

Fair enough if a minor part of his career, his conducting, is ignored, but a minute could have been devoted to the gala performance of Romeo and Juliet he conducted for the American Ballet Theatre at the Metropolitan Opera House, where the orchestra players gave him a standing ovation. Nureyev’s knowledge of music was extensive and he played several instruments. Referring to his start at the Royal Ballet, mentioned above, he annoyed Sir Frederick Ashton further by specifying the music he wanted to go with the short ballet Ashton was to create for him.

While Nureyev died of Aids in 1993 aged 54, he achieved his dream of mounting his own staging of La Bayadère the year before his death.

For those who know little about his life and have never seen him dance, Nureyev is a valuable film, but its choppy and confusing editing and the strange decision not to caption the excerpts as they occur, but (too late) at the end, work against it. And the decision to include contemporary dance sequences choreographed by Russell Maliphant to fill the spaces where no archival footage exists might be innovative, but proves annoying and distracting. Maliphant is a top choreographer but the insertions – and the music – jar with the rest of the film. The ending is also a big disappointment. Surely better archival footage could have been found to illustrate his final farewell (in a wheelchair) and for the random, anticlimactic sequences shown after that sad moment.

If one purpose of the film is to get us to know this dancer as a person, it would have been of interest to note that in his will, along with providing for his surviving sisters, he left his fortune to two foundations devoted to ballet: in particular to the development of young dancers and to helping dancers with health problems.

You can watch the film trailer here: