Joyce Glasser reviews Tracking Edith (July 27, 2018) Cert. PG, 91 min.

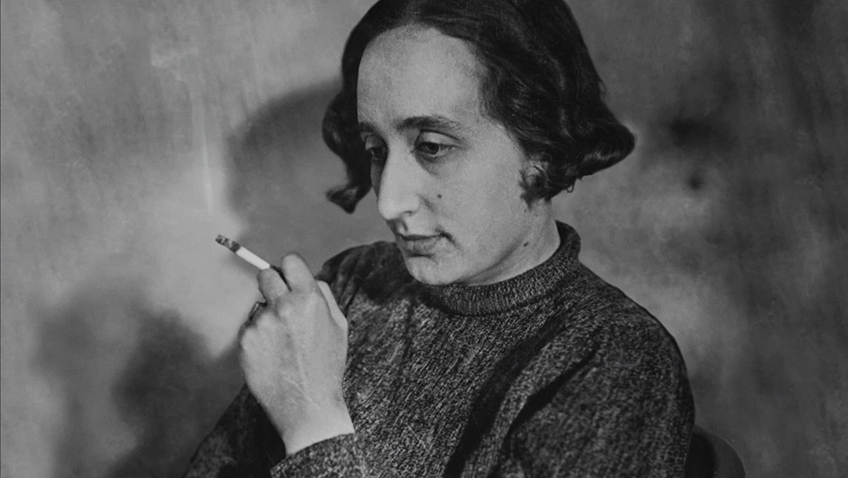

Forget TV’s Who Do You Think You Are? When American-born biographer and filmmaker Peter Stephan Jungk starts investigating his great-aunt Edith Suschitzky-Tudor–Hart he discovers a left-wing, artistic, female Forrest Gump: a talented photographer of the working classes, Edith happens to turn up at pivotal moments on the cultural and political map of world history.

Jungk assures us that his family was baffled when the truth about Aunt Edith (who died in Brighton, Sussex in 1973) emerged. ‘How is it possible that no one in the family suspected Aunt Edith led a double life?’ Indeed, it seems impossible, but then again, as author and historian Nigel West reminds us, spies are not supposed to be obvious. ‘The one thing that stood out in the KGB archives that had never been disclosed before…was the revelation that she had been a major figure in the Soviet intelligence network in London.

Tracking Edith can be seen as a study of influences – mostly male – on a determined, liberated and courageous young woman with a strong and steadfast, if naïve, sense of social injustice. The first person to influence her political outlook was her father, but the times in which Edith lived also played their part.

Born in 1908 Edith’s father ran a bookshop and small publishing house in a working class neighbourhood of Vienna. He was a staunch Social Democrat, but not left wing enough for Edith. She joined the Austrian Communist Youth Movement at an early age, and, having no interest in carrying on the family business, moved to London at age 17 to be trained as a Montessori teacher. When she later returned to Vienna, she discovered that the Montessori affiliates were a strong group of largely Jewish radicals with Bolshevik leanings.

Her political convictions and unfortunate love life brought her into contact with ineligible men and Communist spies, including Arnold Deutsch, a brilliant chemistry and philosophy student with whom she fell in love when still 17. A PhD from the University of Vienna and post-Graduate work at London University were his entrée into British academia as a spy. Deutsch was a rarity as he operated under his real name, posing only as the academic and university lecturer that he really was.

When Deutsch was called to Moscow with his fiancée, he gave Edith a prototype Rolleiflex camera as a going away gift, or a consolation prize. Edith transferred her obsession with Deutsch to the camera and headed for the celebrated Bauhaus School, headed by Walter Gropius, where her first teachers included Josef Albers, Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky.

Some 10% of the students were members of the Communist Student Faction and although Gropius’ replacement, the Swiss architect Hannes Meyer was not a Communist, he did not prevent the Student Faction from meeting and publishing their paper. When Hannes-Meyer was forced out by the increasingly fascist policies that would eventually close the Bauhaus, Edith left the school in solidarity. Meyer went on to teach in Russia, taking a few Bauhaus students with him – but not Edith.

Instead, she went to visit a friend in London where she met Alexander Tudor-Hart, a handsome doctor seven years her senior who was married with a child. He invited Edith to join him at a rally for the Communist Party of GB, where she was spotted chatting with influential, known Communists and expelled by the UK Government.

Returning to Vienna, she was recruited by News Agency Tass to be their official correspondent in Austria, covering Hitler’s rise to power. Alexander left his wife and child to join Edith who was also working as a Communist Party courier. This was extremely dangerous work as in 1933 Austria banned all Communist activities. Edith was caught making a delivery and imprisoned for one month, although in an interview much later her brother, Wolf Suschitzky, claims not to have known.

That same year, an idealistic Cambridge graduate named Kim Philby decided to go to Vienna to witness, first hand, the rise of fascism. He met, and fell in love with, Edith’s friend and fellow courier Litzi Friedman, whose parents rented rooms to Communist sympathisers. When things got too hot in Vienna, Alexander and Edith and Litzi and Kim (they married, so that Litzi could leave the country) moved to London. Here, the film contends, it was Edith’s idea to introduce Philby to Arnold Deutsch, now in charge of recruiting foreign spies for Russia. While her marriage to Tudor-Hart did not last, her social conscience did, primarily in her photographs.

At a display of her work, photographer and curator Duncan Forbes, points out that Edith never adopted the new 35 mm camera, retaining her Rolleiflex throughout her life. ‘The key thing is how you look down at the image held at the waist which means your face is clear and you can look up at the person you are photographing. It’s the type of photograph that encourages dialogue.’ This is not the camera, then, that you would expect a spy to use, but Edith was not a typical spy.

Did Edith regret her actions in light of Stalin’s authoritarian barbarism, a cruel and unjust dictatorship that was almost the antithesis of a socialist utopia? Former KGB officer Alexander Vassiliev doubts that Edith understood the reality of the Soviet Union. ‘I’m not in a position to judge,’ he diplomatically begins, ‘but I don’t think she had a proper idea about the Soviet Union reality, because she had never been to the Soviet Union.’

You can watch the film trailer here: