Joyce Glasser reviews Lizzie (December 14, 2018), Cert. 15, 105 min.

Children who grew up in New England (of which writer/director Craig William Macneill is one) would skip rope to the nursery rhyme: “Lizzie Borden with an axe gave her mother forty whacks; When she saw what she had done, She gave her father forty-one.” The parricide of 4 August 1892 in Fall River, Massachusetts has entered into American folklore and mythology. Along with songs, a TV movie and even a Broadway musical, the late Angela Carter wrote a short story called The Fall River Axe Murders and crime writer Ed McBain wrote a book, Lizzie

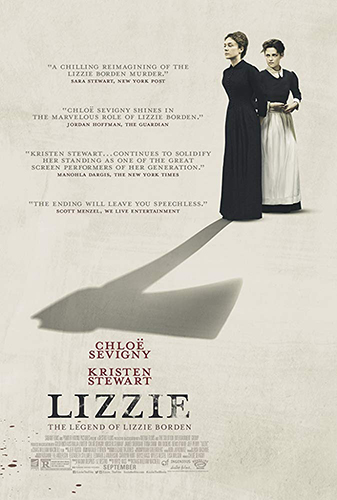

, under his real name, Evan Hunter. Despite the tantalising subject and the starring presence of the wonderful actress Chloë Sevigny (who also co- produces), Lizzie’s thematic and narrative contradictions, lacklustre direction and some questionable casting turn this intriguing subject into an underwhelming experience.

The opening scene takes place on 4 August 1892, a date that Macneill (whose previous feature, The Boy, chronicles the making of a psychopath) returns to three times, closing in on the events that put the image of a screaming Lizzie (Sevigny) standing above a mutilated body in a different perspective. With a caption we go back in time six months earlier when Abby Borden (Fiona Shaw), is taking their new Irish cook and maid, Bridget Sullivan (Kristen Stewart) to her tiny, stuffy attic room.

The opening scene takes place on 4 August 1892, a date that Macneill (whose previous feature, The Boy, chronicles the making of a psychopath) returns to three times, closing in on the events that put the image of a screaming Lizzie (Sevigny) standing above a mutilated body in a different perspective. With a caption we go back in time six months earlier when Abby Borden (Fiona Shaw), is taking their new Irish cook and maid, Bridget Sullivan (Kristen Stewart) to her tiny, stuffy attic room.

Lizzie Borden, 32, and her much older sister Emma (Kim Dickens) live with their father Andrew (Jamey Sheridan) and step-mother Abby in a Spartan, rundown house on Second Street, an odd neighbourhood for a wealthy self-made property developer like Andrew. But Andrew is a miser who treats his grown daughters like children.

Andrew objects to Lizzie going to theatre on her own, cautioning her, ‘you are not helping your cause,’ a warning that is initially cryptic. Lizzie stands firm, declaring that ‘it’s my only respite from this place.’ In the powder room of the theatre, however, there is little respite, when a mean-spirited society lady asks her why their house is so dark. ‘Father doesn’t believe in light;’ Lizzie answers forthrightly, ‘he finds it extravagant.’ Lizzie then demonstrates a sharp tongue that is hardly reticent.

Fall River might not be such a backwater after all, however, as the performance is Alfredo Catalani’s The Wally, an opera that had been performed for the first time at La Scala in January 1892, and the music moves Lizzie. Unfortunately, she suffers from what resembles an epileptic fit (is this ‘her cause’?) in the middle of the show.

Apparently maids in New England went by the generic name of Maggie in those days. Lizzie insists on calling Bridget by her real name and treating her like a real person. When Lizzie discovers that her father is sneaking into Bridget’s room at night, she places broken glass on the threshold and listens for his stifled cry of pain. The women’s relationship quickly turns from supportive friendship to physical love, a relationship Andrew witnesses through the window of the former stable.

The plot is enriched by the presence of handwritten notes threatening Andrew, such as ‘your sin will find you’. Lizzie suggests going to the police about the threats and asks her father if it has something to do with his recent land acquisitions. ‘They are simple folk and don’t know what has happened to their land,’ she explains to an unsympathetic ear, hoping in vain to fend off retaliation from hard-up renters.

Given the death threats, Andrew decides it is time to write a will and invites a relative, John Morse (an excellent Denis O’Hare), to the house for a meeting. ‘I need someone to act on their behalf without sentiment’ he tells John with all the innuendo he can convey. We even hear the word institutionalise in reference to Lizzie. In a later confrontation, John, who plans to grab his share of any inheritance, physically assaults Lizzie, who is spared serious harm by the sudden appearance of Bridget.

There is an odd lack of suspense to any of the scenes in this grisly story, as there is little mounting tension, while the characterisations and motivations do not always gel. It is only at the end, for example, in a remark she makes, that Abby shows signs of being the wicked step-mother. Prior to that, Abby seems to support Lizzie, as in the scene where Andrew forces Lizzie to eat her beloved doves that Andrew has killed and ordered to be served for dinner. We even sympathise with Abby when she lies awake as Andrew returns to their bed after raping Bridget upstairs.

Evan Hunter’s book postulates the theory that Bridget and Lizzie were lovers and Sevigny, as producer, brought Stewart on board with the promise of a feminist take on the famous tale. Hence we have the men as misogynistic rapists and the women as victims of repression. But what is feminist about the gratuitous nudity with both women stripping naked on the fateful day when Lizzie, after a complication, ends up burning her bloodied clothing anyway? And what is feminist about a country maid wearing heavy eye-liner and eye shadow, unless it is related to Stewart’s 2016 deal as the Face of Chanel? There is, however, an ironic twist in the jury verdict which suggests the degree to which the all-male jury underestimate women of social standing.

But there are more general contradictions, too. For instance, who was the credible witness who put Bridget – a prime suspect – outside during the entire morning when a final replay of the action of 4 August shows that she is inside for quite some time?

By contrast, Angela Carter wrote her story after sleeping in the house on Second Street, now a museum and B&B. If Macneill had adopted Carter’s fiendishly dark humour and interpretation, the film would have had its hook, look and a coherent thesis that is closer to the facts than in Sevigny’s hybrid. Carter makes Andrew the personification of Avarice, and Abby the personification of Gluttony, as the real Mrs Borden was short and fat. Andrew apparently adored his daughter (even paying for her to travel to Europe, despite his frugality). On the other hand, Lizzie stopped calling Abby ‘mother’ when she discovered that Andrew was siphoning off land to Abby’s relatives, which points to a very real motivation, absent from the film.

Another culprit in Carter’s story is the weather coupled with the heavy clothing women wore beneath summer dresses. Normal middle-class families are at the seashore during this infernal heat wave – as is Emma – but Andrew had rent to collect. Forcing Bridget to wash windows in the heat would have been cruel, but she is a credible witness maintaining that Lizzie spent the morning in the shade of the garden. Sadly, little of the rich, American gothic atmosphere of Carter’s story comes through in the film.

You can watch the film trailer here: