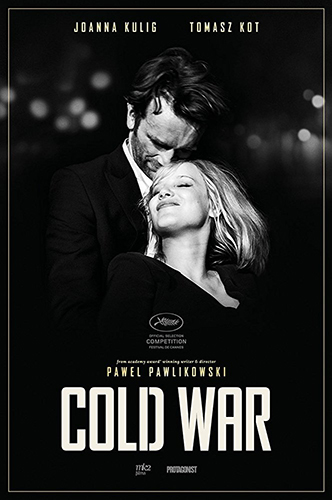

Joyce Glasser reviews Cold War (Zimna wojna) (August 30, 2018) Cert. 15, 88 min.

Director Pawel Pawlikowski was born in Poland in 1957, but lived for most of his life teaching and making films (Last Resort (2000) and My Summer of Love (2004), The Woman in the Fifth (2011)) in or from the UK. Then in 2014, he returned to Poland to make Ida which won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language film and he now resides in Warsaw. Like Ida, Cold War is shot in monochrome, in the intense Academy Ratio (think of The Artist or The Grand Budapest Hotel) and is set, in part, in Poland. And like Ida, the politics are personalised. The cold war here is between two passionate hearts that beat to different drums.

If the two lead characters in Ida covered a lot of political history in their brief 1962 road trip, the two lovers in Cold War (loosely based on Pawlikowski’s parents’ 40-year relationship) cover a lot of political history – and geography – over 15 years, from 1949 to 1964. In Ida Pawlikowski suppressed context, and in Cold War he suppresses time and the narrative that might fill in the gaps. Unusually, Ida DOP Lukasz Zal is credited with the photography. Pawlikowski is credited with the story, direction and image. In this film the images are the story and, merging seamlessly with the actors and the extraordinary music, they tell the story.

If the two lead characters in Ida covered a lot of political history in their brief 1962 road trip, the two lovers in Cold War (loosely based on Pawlikowski’s parents’ 40-year relationship) cover a lot of political history – and geography – over 15 years, from 1949 to 1964. In Ida Pawlikowski suppressed context, and in Cold War he suppresses time and the narrative that might fill in the gaps. Unusually, Ida DOP Lukasz Zal is credited with the photography. Pawlikowski is credited with the story, direction and image. In this film the images are the story and, merging seamlessly with the actors and the extraordinary music, they tell the story.

Wiktor Warski (Tomasz Kot) is a handsome jazz musician and composer who has spent time in Europe before the war. In 1949 he is travelling across war-ravaged Poland with Irena Bielecka (Agata Kulesza), a quiet, nondescript, but principled musicologist who seems to harbour unrequited feelings for her colleague.

They are working under functionary Lech Kaczmarek (Borys Szyc), a cold, predatory and controlling man, with the aim of finding young talent for a new national folklore group called Mazurek. The fortunate performers chosen will be housed, fed, given daily lessons in singing and dance and will be permitted to travel to show off Poland’s post-war national spirit.

The auditions are held in a near-derelict stately home that looks as though it were abandoned by the Polish aristocracy before the war and used as a barracks by the Germans. But now it is the Soviets creeping in, ignoring the Potsdam Agreements and taking back control of Poland.

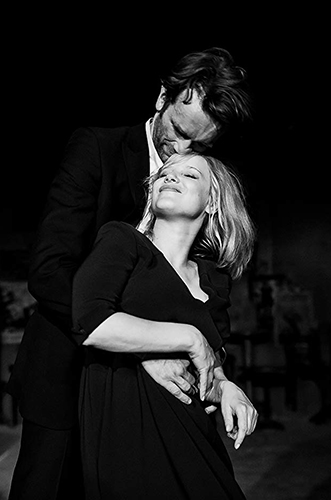

Kaczmarek (who bears a resemblance to Vladimir Putin) declares, ‘no more will the talent of the People be wasted!’ and the auditions begin. So does a romance. It is perhaps lust or love at first sight when Wiktor sees and hears the crude but confident voice of a beautiful, sexy blond teenager called Zula (a sensational performance from Joanna Kulig, who appeared briefly in Ida).

Who is this Zuzanna Lichon known as Zula? She blags her way into the audition by pretending to be a village girl and convincing another contestant that they should sing together. Wiktor is captivated. Irena points out that she does not have a pure voice. Wiktor replies, ‘yes, but she has something else.’ He is looking for star quality and has found it. But it is that ‘something else’ that he cannot shake off and that will determine the course of his life.

Zula stands out enough for her records to be scrutinized. They learn she is on probation for murdering her father. When asked about her father, she says, ‘He mistook me for my mother so I showed him the difference.’ Zula is a survivor.

The three-year period of training and rehearsals is a blissful interlude. But in Warsaw, 1951, with the Mazurek a resounding success, Kaczmarek bows to political pressure to add Soviet songs to the repertoire and hoist a huge picture of Stalin behind the folk troupe on stage. Irena quits in protest and disappears.

The troupe is modelled on the real-life Mazowsze Ensemble that was forced to celebrate the cult of Stalin, but exists today as an example of pure Polish folklore. It is this and so many other authentic details that make the film so captivating, yet darkly unsettling and unfamiliar. Few films inhabit this landscape between history, and unapologetic emotion with the characters in a freefalling collage.

Although Zula and Wiktor are now lovers, she is enjoying her stardom, preferring to ignore the politics for the limelight. Wiktor is uncomfortable with the changes, particularly when Zula admits that she has been asked to spy on him.

After a performance in East Berlin, Zula gets cold feet and passes up her chance to defect to the west with her lover. Wiktor crosses the border alone. In 1954 he is in Paris, playing in a jazz quintet and living with a woman who is clearly not a soul mate. When Zula is briefly on tour in Paris they have a romantic reunion.

The reunions and separations continue: After travelling to Croatia to see her perform, Wiktor is spotted by Kaczmarek, who has designs on Zula. He tips off the police and Viktor is deported. He is back in Paris where, in 1957, Zula shows up – married to a Sicilian husband we never see or hear about again. She married him for a passport that would take her to Paris. Living together in Wiktor’s romantic loft, they also perform together and he helps her record an album. He later learns she was having an affair with the producer (played by the great film director Cédric Kahn).

When Zula tosses her new album – a birthday present from Wiktor – in the mud, he implores her to believe in herself. ‘I do’, she says. It’s you I don’t believe in,’ referring perhaps to the older, weary and disillusioned Wiktor whom she hardly recognises.

One night at a party Zula, drinking too much from what might be restlessness or low self-esteem and insecurity stemming back to her childhood, grabs a stranger and begins to dance wildly to Bill Haley’s Rock Around the Clock, one of many songs chosen for their symbolic as well as musical and period value. Soon after this drunken episode, she leaves for Poland. When Wiktor follows her and is jailed for 15 years, Zula travels to the prison and vows to do anything necessary to get him out.

It looks like Pawlikowski has give up on laborious narrative, linear or otherwise, opting for a pure cinema of images, music, lighting and powerhouse performances from two charismatic actors determined to break your heart. This might be a cop out (like serving frosting without baking the cake), or he might be creating a cinema of evocations that, like poems, cannot be explained without destroying the very thing that makes them so powerful. You might admire the artistry, without feeling engaged with the story. Whether or not you feel the power of any poetry will depend on you.

You can watch the film trailer here: