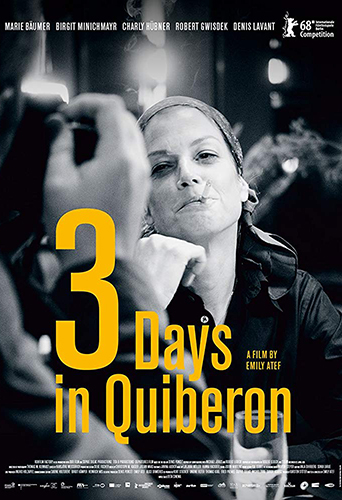

Joyce Glasser reviews 3 Days in Quiberon (3 Tage in Quiberon) (November 16, 2018), Cert. 12A, 115 min.

Thanks to the talents of Romy Schneider lookalike Marie Bäumer; to Thomas W. Kiennast’s atmospheric black and white cinematography; the retro sets and an adherence to the real life Stern Magazine interview with reporter Michael Jürgs (Robert Gwisdek), writer/director Emily Atef’s film 3 Days in Quiberon feels like a docudrama. This is both the film’s strength – as you are voyeuristically introduced to a legend; and its weakness, as Atef sacrifices real drama and the opportunity to contextualise Schneider’s life, for verisimilitude.

We are certainly transported back in time to the 1960s and 1970s when, in most of Europe at least, Schneider was one of the most famous (and talented) movie stars of her generation. The Germans, however, still remember her as the 15-year-old lily white, pure princess Elisabeth of Austria in her 1955 film, Sissi (and its two sequels) and refuse to recognise the more challenging and varied roles (The Train, César et Rosalie, The Things in Life, The Swimming Pool, The Cardinal, The Trial) that she took on in France and, briefly, in the USA (Good Neighbour Sam, What’s New Pussycat).

We are certainly transported back in time to the 1960s and 1970s when, in most of Europe at least, Schneider was one of the most famous (and talented) movie stars of her generation. The Germans, however, still remember her as the 15-year-old lily white, pure princess Elisabeth of Austria in her 1955 film, Sissi (and its two sequels) and refuse to recognise the more challenging and varied roles (The Train, César et Rosalie, The Things in Life, The Swimming Pool, The Cardinal, The Trial) that she took on in France and, briefly, in the USA (Good Neighbour Sam, What’s New Pussycat).

If you are not familiar with Schneider’s life, the exposition, cleverly hidden in the interview, will fill you in. When 20-year-old Schneider moved to France with Alain Delon, the former child star was escaping her controlling, profiteering actress mother; an allegedly sexually abusive step-father and her stifling, regimented life that, ironically, mirrored that of her character, Elisabeth of Austria.

Schneider’s passionate romance with Delon, arguably France’s biggest movie star in the 1960s, lasted from 1958 to 1963 during which they made several movies together. They became Europe’s powerhouse show business couple, although the Germans never forgave her desertion when she went to France to make Christine with Delon in 1958.

In 1969 the former couple reunited under director Jacques Deray to make The Swimming Pool which was a hit in France and proved influential. In 2003, François Ozon’s erotic thriller, The Swimming Pool was compared (unfavourably in the main) to Deray’s film and in 2016, Luca Guadagnino (the director of Call Me by your Name) made A Bigger Splash, loosely based on Deray’s film.

With fame, came the spot light and showbiz gossip. By 1981, her tumultuous private life was overshadowing her work – and it was about to get worse with the recent separation from her second husband. The Stern interview was meant to give Schneider a chance to counter this gossip and the negative rumours that stalked her and were affecting her personal and professional life.

When sharply observant, manipulative Jürgs and his sympathetic photographer and flirtatious old friend Robert Lebeck (Charly Hubner), arrive at the resort in Quiberon, Schneider is on a detox diet. As she tells her Austrian friend Hilde Fritsch (Birgit Minichmayr), who has just arrived at the hotel to lend Schneider emotional support, the detox regime was not preparation for her next film, The Passerby, but was a last ditch attempt to keep custody of her son David, two years after the suicide of his father, Harry Meyen a German actor/director.

After her divorce from Meyen, in 1975 Schneider had married her private secretary Daniel Biasini, but they separated (with a baby daughter) at the time of the Stern interview. Within a year of the interview, both David (who died in a freak accident at his step-parents’ home) and Schneider (of a heart attack following an operation) were dead.

But in a restaurant on the old port, where the foursome retire after the first, intense, interview, 42-year-old Schneider is a film star above all. As adoring fans approach Schneider’s table, the detox goes and the champagne flows. A contrite Jürgs watches Schneider transform into the warm, generous-hearted, charismatic, life of the party that the interview would never reveal.

After this long scene with its shades of La Dolce Vita, the film becomes a series of meetings in hotel rooms in which the interview unofficially continues. Jürgs, Lebeck and Schneider meet again and Jürgs presses deeper. Lebeck reluctantly snaps photos, but is increasingly uncomfortable about his colleague’s exploitation of a vulnerable woman to whom he has always been romantically attracted.

In further scenes, Lebeck and Schneider become intimate and a sidelined Fritsch, who is trying in vain to shield her friend from Jürgs’ assault, has a frosty breakfast with the journalist. While Fritsch is the only fictional character in the film, there to provide an expositional sounding board outside of the interview, it is believed that Schneider did have a friend visiting at the time.

This somewhat anti-climactic series of alcohol fuelled, hotel-room encounters in the early hours of the next morning or the more sober heart-to-hearts, as between Fritsch and Jürgs, does grow tiresome. The film needs a more climactic dramatic arc in the second half to sustain and propel the narrative.

The acting from all four players, however, cannot be faulted, nor can Thomas W. Kiennast’s cinematography which captures the anodyne hotel, the windswept beach out of season and the claustrophobic hotel rooms so well that you can almost see the stale odour of damp sheets, unmade beds, wine glasses and uncollected room service.

You can watch the film trailer here: