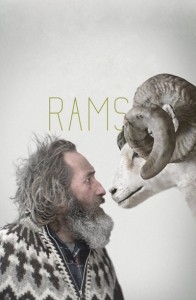

Joyce Glasser reviews Rams (Hrútar) (February 5, 2016)

The two estranged brothers at the heart of documentary film maker Grimur Hákonarson’s Rams, would have been at home in fellow Icelandic Writer/Director Benedikt Erlingsson’s 2013 film, of Horses and Men.

Like the weird inhabitants of Erlingsson’s alien world, brothers Gummi (Sigurður Sigurjónsson) and Kiddi (Theodór Júlíusson) live alone, though on the same farm land, with an inhospitable, rugged landscape, dependant only on the animals that are their companions as much as they are their livelihood.

Rams won the Un Certain Regard prize this year at the Cannes Film Festival, a prize intended to recognize young talent and to encourage innovative and daring works. At 39, Hákonarson is not exactly young, and the film is neither particularly daring nor innovative; but in this, his fictional feature film debut, Hákonarson’s knowledge of his subject combines with offbeat humour, visceral images and truly moving, dramatic moments to tell an immensely satisfying tale.

Rams won the Un Certain Regard prize this year at the Cannes Film Festival, a prize intended to recognize young talent and to encourage innovative and daring works. At 39, Hákonarson is not exactly young, and the film is neither particularly daring nor innovative; but in this, his fictional feature film debut, Hákonarson’s knowledge of his subject combines with offbeat humour, visceral images and truly moving, dramatic moments to tell an immensely satisfying tale.

Gummi and Kiddi, two grey bearded bachelor brothers of around 60, live in neighbouring farm houses surrounded by a spectacular expanse of unspoiled rocky meadows and ominous looking hills that in winter are covered in snow.

They were born on this farm and have lived there for the past 40 years without speaking to one another. Half way through the film, we learn about their late father’s hand, perhaps a well-meaning one, in the estrangement.

When Kiddi’s ram beats Gummi’s in a regional competition by half a point due to the thickness of its back muscle, Gummi quietly leaves the competition to examine his brother’s cherished winner. When Gummi declares to the regional vet that the ram is infected with BSE or Scrapie as they call it, it is a catastrophe for all the farmers, although insurance will help with the cleanup costs and the repurchase of new herds.

For Gummi and Kiddi, however, it means the extinction of their beloved Bolstader breed. As neither man has children, this is tantamount to the extinction of their own line and Hákonarson captures this symbolic connection convincingly. In the middle section of the film we observe how each man rebels against the government decree in his own way. Ironically their reactions bring the brothers together in a common pursuit larger than their stubbornly embalmed argument.

This would be a one-dimensionally bleak story were it not for Hákonarson’s stylistic techniques for distracting us.

This would be a one-dimensionally bleak story were it not for Hákonarson’s stylistic techniques for distracting us.

These include an almost documentary sequence of engrossing shots showing the hard, physical labour involved in sheep farming and the bachelor’s day-to-day routine.

He also entertains us with unexpected, arresting shots (Kiddi staggering into Gummi’s parlour stark naked) and subtle humour. We laugh at Gummi’s futile attempts to relax in his bath and the way Kiddi’s intelligent sheep dog obligingly transports messages between the two warring factions.

What turns this visceral tale into a kind of poetry, however, are Hákonarson’s images, from hard wood and ice to soft flesh, that reoccur in visual echoes of one another. Kiddi, who refuses to clean his barn after his sheep are slaughtered, turns to drink and is found lying half dead in the snow by a veterinary official.

This image is echoed later in the film when, humorously, Gummi spots his brother supine in the snow. He scoops the heavy blob into his tractor’s loader, drops him, literally, at the door of the hospital and then drives away. The image of a frozen body in the snow recurs in a more tragic echo, all the more poignant in that this time, there are two.