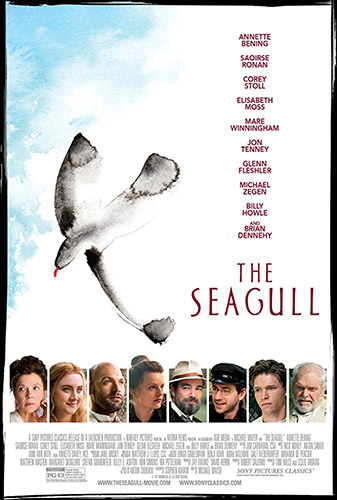

Joyce Glasser reviews The Seagull (September 7, 2018) Cert. 12A, 98 min.

A Tony Award winning playwright who is also a film director sounds like the right combination to tackle the first ever film adaptation of Anton Chekov’s elusive and tricky masterpiece, The Seagull. That Michael Mayer has had more success with directing theatre (winning Tony Awards for Spring Awakening and Thoroughly Modern Millie) than feature films (the forgettable Flicka and touching, though flawed A Home at the End of the World), is evident here, even with three terrific big name actresses and generally good, if occasionally over-egged performances.

The Seagull is a play rich in themes and history. At the surface, it is a story of unrequited love, not just between one couple, but along a chain of characters, representing almost class and profession of Russian society at the turn of the century. It is also a story of youth and age, and, set in the theatre milieu which Chekov knew well, with its risky play within a play, a satire on the fin de siècle artistic and entertainment scene. But that unrequited love is a symptom for a greater malaise. For The Seagull is about the artist’s balancing love and creation and their continual need for the approval of others.

The Seagull is a play rich in themes and history. At the surface, it is a story of unrequited love, not just between one couple, but along a chain of characters, representing almost class and profession of Russian society at the turn of the century. It is also a story of youth and age, and, set in the theatre milieu which Chekov knew well, with its risky play within a play, a satire on the fin de siècle artistic and entertainment scene. But that unrequited love is a symptom for a greater malaise. For The Seagull is about the artist’s balancing love and creation and their continual need for the approval of others.

At the top of the list is the aristocratic actress Irina Arkadina (Annette Bening), a star at the height of success and fame, but worried about her fading talent and replaceable talent. After performing at the Imperial Theatre in Moscow, Irina and her lover, a famous, but much younger novelist Boris Trigorin (Corey Stoll) visit Irina’s brother Sorin (Brian Dennehy) at his lakeside estate which is also her country home.

There, her insecure son Konstantin (Billy Howle, from On Chesil Beach) is putting the finishing touches on a play that he has created in a bid to bring the latest fashion, symbolist drama, to the staid tradition of melodrama. As the events at Sorin’s estate evolve, however, it becomes apparent that the play is equally Konstantin’s latest attempt to win the approval of his absentee mother and of his innocent girlfriend from a neighbouring estate, the would-be actress, Nina (Saoirse Ronan).

Irina, however, very much in her element and flirting with Boris, mocks her son’s play and talks during the performance. Sorin is not the only one who feels Irina is too hard on her son; Masha (Elisabeth Moss), the alcoholic and snuff sniffing daughter of Sorin’s estate manager (Glenn Fleshler) and his wife Polina (Mare Winningham) is madly in love with Konstantin.

Konstantin has as little interest in Masha as she does for the desperate school teacher Medvedenko (Michael Zegen) who bores everyone with his complaints of his poverty and his self-pity. It is just a shame that Mayer allows Moss to overdo it, turning Masha into a farcical, comic character.

Even Polina loves in vain: locked in a loveless marriage, she adores Dr Dorn (Jon Tenney), a kindly voice of reason and objectivity. They have enjoyed a sexual relationship, but he is less enthusiastic about continuing it. Polina’s cruel husband flatters Irina and seems to bask in the glamour of the lady of the house, but he makes it clear that he will not take orders when it comes to the estate he manages.

The play-within-a play gives Ronan a chance to parody bad acting, something only good actresses should attempt. Ronan is very much the British actress of the year after she was nominated for an Academy Award for her leading role in Lady Bird but here she has an almost impossible task. She has to convince us that she has what it takes to seduce Boris, while at the same time, play a guileless, ambitious young woman that does not have what it takes to succeed in the cut-throat world that Irina has conquered – at a cost. Her school-girl crush on Boris eclipses her consideration of Konstantin or his mother.

Bening is made for the role of Irina, and whether she is the confident prima donna, the misguided mother, the enticing lover or the wronged older woman, she convinces us that she is all of these personas in one.

While the play examines the relationship that each artist (Irina, Konstantin, Boris and Nina) has with his or her respective craft, Mayer’s production focuses on Nina’s arc. At the beginning she tells Konstantin that her parents are against acting, and their concerns are justified. We never know the exact cause of Nina’s breakdown, but her realisation, or acceptance, that endurance and fortitude are more honourable than success in the eyes of society comes too late to save Konstantin.

Unlike Nina, Konstantin becomes so obsessed with perfection – and so covetous of the success of others – that he is unable to function. Boris is never fully satisfied – with his stories or his mistresses and is always eager to start anew. All of the artists seek the approval of others but are less able to rise above their need than Nina.

The film is a faithful, if necessarily truncated, adaptation by scriptwriter Stephen Karam, but it never gets under your skin or really captures the essence of Chekhov’s vision. For the originality of Chekhov’s play was itself met with harsh criticism, much as Konstantin’s was, for its naturalistic depiction of real characters in all walks of life. The problem is not Mayer’s theatrical take on the play, but, on the contrary, his attempt to remind us that we are watching a film with his use of a fussy, hand-held camera dashing about the sets and among the characters.

If Mayer and Karam wanted to distinguish their film from the countless productions of the play – from the first production in October 1896, to last year’s Chichester Theatre Festival revival that transferred to the National Theatre – he could have, for starters, changed the period from 1904 to either the theatre world or even Hollywood in a more modern time. And he could have changed the setting from the lakeside farm outside of Moscow. Since most of the film was shot in New York and Sorin’s estate on a rocky hilltop hardly looks like a Russian agricultural domain, it would have been easy enough to do.

You can watch the film trailer here: