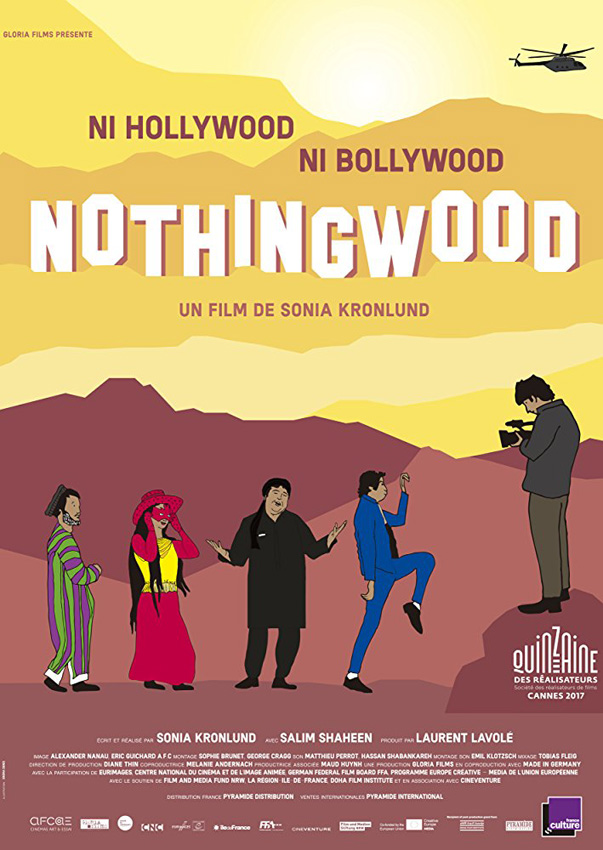

Joyce Glasser reviews The Prince of Nothingwood (December 15, 2017) Cert 15, 86 min.

The title of Sonia Kronlund’s documentary is explained by Afghan film producer/director/actor Salim Shaheen. ‘Here, it isn’t Hollywood, it isn’t Bollywood, it’s Nothingwood because they pay nothing,’ Salim tells Kronlund, laughing about the financial downside of filmmaking in an orthodox, war-torn, impoverished and sometime Taliban-controlled country. Yet Shaheen, who will not allow his two wives to be seen or heard in the documentary, is addicted to making and starring in movies. The Prince of Nothingwood shines a light on the surreal world of DIY Afghan filmmaking where you don’t pay for props such as tanks, guns and bombs, you just film around them.

French/Swedish Director Sonia Kronlund has, for the past 15 years, specialised in making television and radio documentaries in Iran and Afghanistan, but realised one day that she had missed something important. That something is force of nature Salim Shaheen and his 110 ‘C’ movie back catalogue. He is a one-man ‘pocket of resistance’ in the war-ravaged country where entertainment, when and where it is even allowed, is not a priority.

French/Swedish Director Sonia Kronlund has, for the past 15 years, specialised in making television and radio documentaries in Iran and Afghanistan, but realised one day that she had missed something important. That something is force of nature Salim Shaheen and his 110 ‘C’ movie back catalogue. He is a one-man ‘pocket of resistance’ in the war-ravaged country where entertainment, when and where it is even allowed, is not a priority.

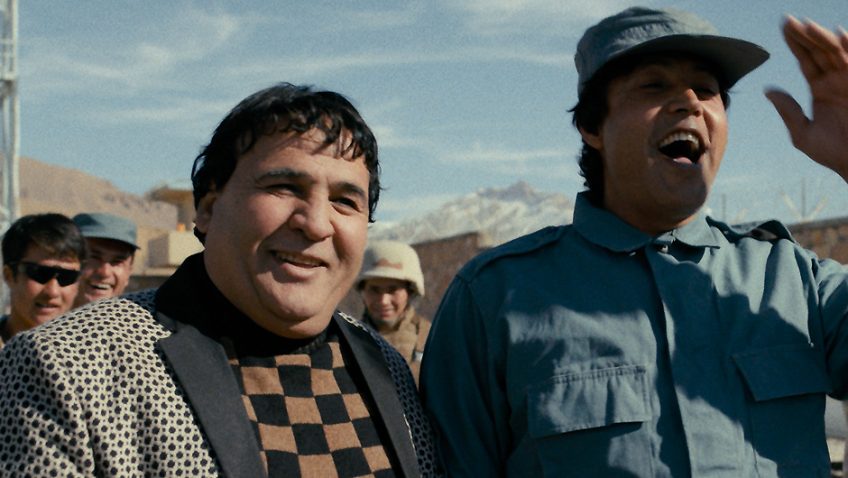

Though he is an unabashed control freak and an attention grabber, the high-spirited Salim is generally loved and admired. One colleague tells us that, ‘we live in a savage world and Salim managed to get us interested in cinema.’

The reality of this savage world is never far away. And while there is insurance in Western countries when an actor is ill or dies, or when the film is confiscated or otherwise destroyed, here nothing is insurable. The cast and crew show up to finish one film on crutches, bearing the scars of a real explosion in which one intrepid soul lost his life. If proof is needed, the British Board of Film Classification has given the documentary a 15 rating for depictions of ‘real dead bodies.’

This is macho filmmaking and Salim tells us that Rambo (he doesn’t say Sylvester Stallone) is a role-model. That said, his passion for film arose from Bollywood not Hollywood movies that he saw as a child when he snuck into a near-empty movie theatre. But Salim had seen enough Hollywood films to know how to feign being dead to save himself after a Russian plane crash.

While Kronlund is familiar with the security rules for foreign filmmakers in Afghanistan security is largely ignored by Salim, who leaves his vehicle to help dislodge a wagon is stuck in a rut. The heroism of his characters spills into real life. ‘You should help the elderly and the weak,’ he tells us.

As Kronlund follows Salim’s shooting of his 111th (autobiographical) movie, she occasionally expresses concerns for their safety, Salim is fatalistic about life. When they leave Kabul for a remote (but safe) location in Bamiyan, Salim does take the precaution of flying as the roads are too dangerous. Sadly, the Taliban destroyed most of his phenomenal natural sets: the monumental statues of Buddhas carved into the rock formations the 4th and 5th centuries.

While Salim’s films might not be examples of great filmmaking, (his brother tells us that his first film had no story and was incoherent), he is Afghanistan’s most popular actor/director and, as we learn in one amusing scene, even the Taliban seek them out on the black market. While Salim’s films are patriotic, he does not portray the Taliban as the enemy or offend them. Salim is a canny producer who wants to reach the widest possible audience and even the Taliban need a bit of escapism.

One of the film’s pleasures is meeting the crew and its actors, including one of Salim’s sons. He plays his father as a young man with little of his dad’s enthusiasm, prompting dad, the director to shout, ‘Act better!’ Salim’s mother is played by Qurban Ali, a tall effeminate actor whose attraction to the profession is obvious. Ali likes dressing as a woman and there’s no competition for the female roles. Ali is a pretty good actor whose feminine mannerisms on and off the set are not only tolerated, but appreciated. That people snigger at this form of transgression, however, suggests that there is not much sexual equality in Afghanistan, and it probably helps that Ali has a wife and children. Kronlund is accepted as an a-sexual, non-Muslim being from another country.

One of the shortcomings of the film is that we never really get a sense of the films Salim has made from the occasional short clips in the documentary. It is hard to know what to make of the autobiographical film being shot for the documentary, where Salim’s ‘mother’ (Ali) has a fit when she sends her son out to buy bread and he returns another person. ‘Oh my god,’ Ali wails, falling to his knees in despair, ‘my son is a dancer!’

You can watch the film trailer here: