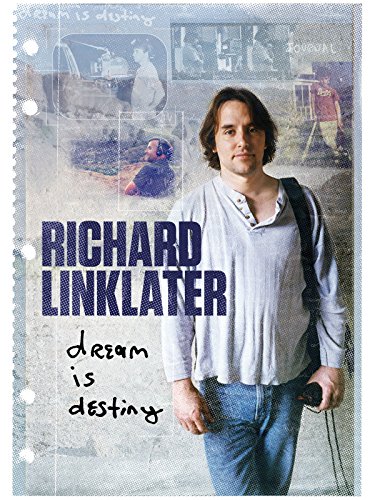

Joyce Glasser reviews Richard Linklater: Dream is Destiny (November 4, 2016)

Dream is Destiny is an affable, cheery, humanistic and talkative documentary about a director whose films fit that description. We spend time on the set with Linklater, but that does not really tell us much about his unique style of filmmaking. Unlike the documentary, by friend and Austin Chronicle founder Louis Black and Karen Bernstein, Linklater’s films have an innovative and slowly revealing poetic quality to them that makes many of them matchless in the annals of cinema.

Matchless, but difficult to pin down like the man himself. Maybe it is because Richard Linklater’s films defy classification (The Newton Boys, a genre film and flop, being an exception) that we can never quite get a handle on them; or maybe it is because they are so varied and unconcerned with Hollywood star power. Ethan Hawke, Linklater’s regular collaborator, was an up-and-coming name when he starred in Before Sunrise: a romantic comedy and a coming-of-age story, but not like anything we have seen before in either genre. Or maybe it’s because in place of superheroes, we have ordinary, recognisable people reaching out to one another; or in the place of contrived plots were have wonderful characters and delectable conversation. Or, in place of violence, noise, and CGI effects we get a cinematic humanism that puts us in touch with our youth and makes us feel young again.

Matchless, but difficult to pin down like the man himself. Maybe it is because Richard Linklater’s films defy classification (The Newton Boys, a genre film and flop, being an exception) that we can never quite get a handle on them; or maybe it is because they are so varied and unconcerned with Hollywood star power. Ethan Hawke, Linklater’s regular collaborator, was an up-and-coming name when he starred in Before Sunrise: a romantic comedy and a coming-of-age story, but not like anything we have seen before in either genre. Or maybe it’s because in place of superheroes, we have ordinary, recognisable people reaching out to one another; or in the place of contrived plots were have wonderful characters and delectable conversation. Or, in place of violence, noise, and CGI effects we get a cinematic humanism that puts us in touch with our youth and makes us feel young again.

The film begins with a sequence out of Linklater’s first film, Slackers, a film that not only launched Linklater’s career, but his style of filmmaking and, probably cemented his decision to remain in Austin, Texas despite the call of Hollywood for his second feature, Dazed and Confused. While looking around for a location to film where they could lay dolly tracks without huge expense, would not need permits or encounter interference, the answer was downtown Austin. This was a gift to a cash-strapped first-time filmmaker and create a bond with the city where he moved to study theatre after dropping out of college in his hometown, Housto, when an injury prevented him playing baseball. Not that most first time filmmakers would dream of making a film about a group of unmotivated, college-educated, profligate young men using dolly tracks, but Linklater’s idea was to elevate this unsung segment of his generation into something almost epic and poetic and put them on the map of America.

Linklater’s decision to keep a physical distance from Hollywood was not just symbolic of his independent status. He did not want to be influenced by or sucked into the system and says that he never made a film he did not believe in.

As an independent filmmaker, he wrote and directed his films, but often produced and acted in them as well. And as with all Independent filmmakers, since funding a film is a major preoccupation the documentary addresses this issue, particularly with School of Rock (a studio film) and the very risky, experimental and unscripted Boyhood. There are only two films in Linklater’s filmography that another director could have made and both are studio films that he did not initiate: The Bad News Bears (rightfully ignored in the documentary) and The School of Rock (which, star Jack Black confirms, Linklater put his stamp on. In his hands a formulaic, high-concept comedy is something truly magical. Not that Jack Black or Hollywood would ever have had Linklater on their list of possible directors. It was the visionary producer Scott Rudin who not only had the imagination to see that Linklater was the right man for the job, but convinced Linklater (demoralised after his experience with the Studio’s crass marketing of Dazed and Confused) that he was.

Chronology aside, one reason why the documentary begins with Slackers is because Linklater’s character in the film was so very much like Slacker’s writer/director/co-producer himself. A starry-eyed young man (Linklater) is in the backseat of a taxi looking around while chewing an indifferent taxi driver’s ear about the existential choice of his being in the taxi. What if he had walked, or waited for a bus or hitchhiked, and a beautiful woman picked him up….Unlike the ‘what ifs’ in Philip Roth’s devastating coming-of-age novel Indignation, just released as a film, the ‘what if’s here are light-hearted, but the concept of the roads taken and not taken permeate through Linklater’s life and films.

The whole concept behind Linklater’s masterpieces, the ‘Before Sunrise/Sunset/Midnight trilogy and Boyhood is this notion of choices and roads taken and not taken. In Before Sunrise a young, scruffy American tourist (Ethan Hawke) recently jilted by his girlfriend in Spain, is travelling to Vienna to catch a plane back to America. He sits opposite a beautiful, cultured French student (Julie Delpy) on her way back to Paris. When the train pulls into Vienna, the young man asks her to join him in wandering around the city until his plane leaves the following morning. The girl has minutes to decide to get off the train with a total stranger or continue on to Paris as scheduled. Her decision changes both of their lives forever. The same pair meet up 9 years (in real life as in the film) later in Before Sunset and face another decision that keeps viewers enraptured until the sublime ending.

Like Slacker, the ‘Before’ trilogy and Boyhood, are good examples of Linklater’s trademark collaborative style. He admits that he doesn’t like to make films alone and always works with others. Only a very self-assured and director would feel this way, but the performances Linklater was after in these largely plot-less films, character-driven films depended on the actors not only co-writing the scripts and feeling a part of the creative process, but becoming the characters.

This is especially true of Boyhood, which, while autobiographical (like his latest film, Everybody Wants Some), is a universal coming-of-age story told in ‘real time’ and filmed over 12 years. It is also a film about choices and how people, places and the smallest of incidents or even a word, combine to turn the boy into the man – or, in Linklater’s case, a slacker into a successful Academy Award nominated director. But it is indicative of how subtle Linklater’s genius is that when his daring, ground-breaking and epic and life-affirming film Boyhood was nominated against Hollywood’s innovative Birdman, it was Birdman that won.

You can watch the film trailer here: