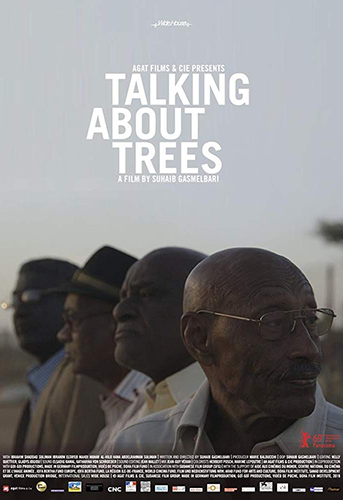

Joyce Glasser reviews Talking about Trees (January 31, 2020), Cert. U, 93 min.

There have been many films in the last few years about the plight of refugees from war torn and autocratic regimes but Talking About Trees focuses on four sexagenarian filmmakers trying, against the odds, to revive an old cinema in the cultural wasteland of Hassan al-Bashir’s Sudan. What makes their plight so sad and depressing is that these cultivated, passionate men knew some success before finding themselves in a country where a new, Islamic regime shut all the cinemas. What makes us care about them is their sense of humour, resilience and faith in the power of cinema to transform lives. Having no outlet for their talents and skills, they reminisce, and embark on a project to turn the derelict Revolution Cinema in Khartoum into a free outdoor venue, showing films that the public want to see.

Fittingly, the film begins during a power cut that has lasted for four days. That is never good in the cinema industry, but Sudanese filmmakers Ibrahim Shaddad, Manar Al Hilo, Suleiman Mohamed Ibrahim and Altayeb Mahdi, all of whom were making films in the 1970s and 1980s, are used to deprivation and frustration.

Fittingly, the film begins during a power cut that has lasted for four days. That is never good in the cinema industry, but Sudanese filmmakers Ibrahim Shaddad, Manar Al Hilo, Suleiman Mohamed Ibrahim and Altayeb Mahdi, all of whom were making films in the 1970s and 1980s, are used to deprivation and frustration.

These founders of the Sudanese Film Club have been reunited by Sudanese-born filmmaker Suhaib Gasmelbari, who was deeply touched when he first witnessed the group’s efforts to show a film outdoors in a dust storm and wanted to make their project the focus of his first feature length film. At times the expository nature of the dialogue reveals that their reminiscences are partly for our benefit, but they exude warmth, humour and the friendship based on a precious shared experience.

Goofing around in the dark, Ibrahim Shaddad wraps his bald head in a blue veil and mimics Gloria Swanson’s dramatic speech from Sunset Boulevard: ‘There’s nothing else, just us and the cameras and all you wonderful people out there in the dark,’ he recites to a small light, and a friend pretending to be capturing it all with a camera.

Ibrahim Shaddad studied filmmaking in the GDR, and from the clip of his 1964 film The Hunting Party, he was a master of atmosphere and sound effects. His film, The Rope won a prize at the Damascus Film Festival in 1987, but in 1990, after being detained and tortured in the coup of 1989, he went into exile in Canada and Egypt. He returned, as did Altayeb Mahdi, who was working for The Arab Radio and Television company in Egypt (where he had graduated from film school in 1977).

The friends find a letter that Altayeb wrote to them in 1995 from his self-imposed exile, recalling their lives together before the coup with nostalgia. ‘Now ignorant tyrants have torn our past to shreds and emptied our lives of substance.’ Altayeb dislikes working in television and longs to return to filmmaking – and to Sudan.

Altayeb Mahdi in Talking About Trees

Altayeb (who directed several artistically daring short films, including The Station (1988) and The Tomb (1976) and Shaddad appear on radio talk show The Front Page where the topic is Sudanese Cinema, The Hero is Dead. After being introduced by the female radio host, Shaddad says subversively, ‘you can either die naturally, or be murdered by a traitor. The death of cinema was not natural at all. It died suddenly. To find the cause of the death of a hero, look to the traitor.’ Strong stuff for a country (this was shot before al-Bashir was sent to the International Criminal Court for trial) where repression and censorship is pervasive. Many of the group’s films have been banned.

In one scene, we again find ourselves in a kind of derelict soundstage or warehouse, but like many details of the men’s lives, we are never told about it. We learn nothing of their family life, what their children (if any) do, and how they survive financially. What is apparent is their obsession with and knowledge of world cinema. They find a dusty Arriflex lens, videos of Claude Brasseur’s Le Souper and Truffaut’s La Peau Douce and a 16 mm camera reel, that elicits soft cries of, ‘Oh, Buñuel.’

When the friends uncover Shaddad’s notebooks from his film studies in Germany, Shaddad recalls his inspirational teacher who urged his students to note all their observations to enrich their imaginations. ‘Describing a bridge, a tree or an alley could help us write.’ The film’s title, (perhaps so subtle as to be misleading) comes from Brecht’s famous quote: “What kind of times are these, when to talk about trees is almost a crime because it implies silence about so many horrors?”

Suleiman Mohamed Ibrahim, Manar Al Hilo and Altayeb Mahdi in Talking About Trees

A particular discovery turns nostalgia into thoughts of the coup (‘the traitor’) that introduced a thirty-year, hard-line Islamic regime. Looking at the script and photos of costumes, props: everything needed to begin production of his film, The Crocodile, he recalls. ‘Then the military coup happened. All that’s left is the photos.’

Suleiman Mohamed Ibrahim studied in Moscow from 1973 to 1978 and we see photos of his graduation party. After being awarded the Silver Prize for his short film It Still Rotates at the Moscow International Film Festival 1979, Ibrahim returned to Sudan with optimism and refused to go into exile after the coup. We hear part of his heart-wrenching telephone call in rusty Russian to the VGIK Institute of Cinematography. This is a vain attempt to track down his graduation film, ‘Africa, Jungle, Drum and Revolution.’ He adds, ‘This film is very dear to me.’

Once the men come to an agreement with a businessman who seems to own the site, the challenges of obtaining a licence and physically turning the space into an outdoor cinema dominate the film. The four men canvas the youth playing football nearby to see what they want to see (recent action, superheroes, American films and some Bollywood fare). It is refreshing to hear the young men (sadly there are no women), brought up on state sponsored television or what they can watch on their phones, express a desire to see films in a group and on a big screen. In one surreal scene, Shaddad leads a camel into the empty cinema space one evening. Looking out at the vast space, he tells the bemused animal that once this would have been crowded. ‘But that was before you were born.’

While the posters for the inaugural film, Tarantino’s Django Unchained, are being made and posted and the friends query what kind of projector is needed, other, darker, practical concerns emerge. There are six mosques surrounding the cinema each with loudspeakers announcing prayers at just the time they want to show the film. Shaddad jokes that by the time the cinema is ready, two more mosques will have been built. They all crack up at the thought of a passionate film kiss being interrupted by the amplified declaration, ‘God is Great!’

When you are beyond tears, there is always laughter.

You can watch the film trailer here: