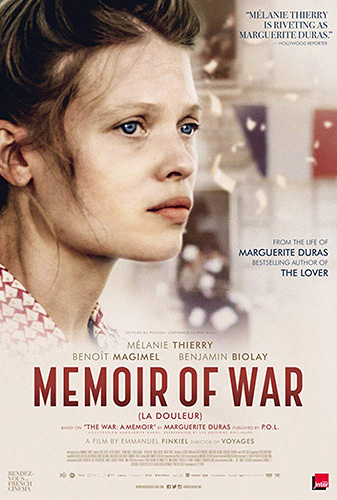

Joyce Glasser reviews Memoir of War (La douleur) (May 24, 2019), Cert. 12A, 126 min.

There is a square in Paris’s 13th arrondissement named after Robert Antelme, but the Resistance fighter, survivor of Buchenwald and author of The Human Race, his own memoir about his experiences in concentration camps, is best known as Marguerite Duras’s absent husband in her autobiographical WWII memoir, La douleur

published in 1985. Eleven of Duras’s books have been made into films, some by Duras herself. Several of them, including Hiroshima Mon Amour (for which she wrote the script), The Lover and The Sea Wall are about her memories of war and childhood, both of which marked this prolific and multi-talented writer/filmmaker. La douleur

, literally ‘pain’, might not be the easiest book to turn into a film, but there are other challenges, some of which this ambitious adaptation does not surmount.

Writer/Director Emmanuel Finkiel (a former assistant director to ‘Three Colours’ director Krzysztof Kieślowski and Jean-Luc Godard) focuses Memoir of War on a blend of two of La douleur’s six chapters: Duras’s relationship with a French agent of the Gestapo called Pierre Rabier (Benoît Magimel) through whom she hopes to obtain news of, if not clemency for Robert Antelme (Emmanuel Bourdieu), as he is called in the memoir); and her anguished wait for him to return after the liberation of Paris.

Writer/Director Emmanuel Finkiel (a former assistant director to ‘Three Colours’ director Krzysztof Kieślowski and Jean-Luc Godard) focuses Memoir of War on a blend of two of La douleur’s six chapters: Duras’s relationship with a French agent of the Gestapo called Pierre Rabier (Benoît Magimel) through whom she hopes to obtain news of, if not clemency for Robert Antelme (Emmanuel Bourdieu), as he is called in the memoir); and her anguished wait for him to return after the liberation of Paris.

However, in omitting sequences from the other chapters, we are deprived of the complete picture of how pain and war change people, and of the moral ambiguity that runs throughout the book. He skirts around Marguerite’s condemnation of De Gaulle for choosing to rewrite history by lauding the Allies’ ‘glory’ over the people’s ‘pain’ and refusing to mention the camps or give credit to the Resistance, missing a vital source of Duras’s motivation for ensuring that ‘pain’ takes its place in history.

In the chapter on Rabier (who might have stolen his nom de guerre from a dead French citizen) Marguerite’s mind frequently turns to murder, not only the Resistance’s plan to murder Rabier before he flees Paris, but her own desire to shoot him in the back when he is cycling in front of her. He is the French-literature- loving Gestapo agent who arrested her husband and (omitted from the film) Robert’s 24-year-old sister, who dies in a concentration camp. Although respectful of Marguerite’s literary reputation, Rabier still lies to her about Robert and hopes to extract information about their Resistance cell while wining and dining her.

Finkiel gives us a fascinating depiction of Resistance fighters living among collaborators and Germans in an occupied capital, and of the complicated, topical process of repatriating prisoners and refugees after the Liberation. It might not, however, be clear to audiences that in early scenes Marguerite is at the Gare D’Orsay trying, with fake documents, to obtain information on deportees and prisoners for a paper she founded to disseminate this information. As the film makes clear, information is as precious as food for those waiting in a void.

Nor is it made clear that Marguerite was a central part of Robert’s Resistance cell, a cell headed by François Mitterrand AKA François Morland (Grégoire Leprince-Ringuet) who, in 1981 became France’s longest serving President and its first left wing President since 1958. Perhaps because the film is confined to Marguerite’s point of view, Finkiel omits the memoir’s engrossing, and astonishing account of Mitterrand’s heroism in snatching Robert from the jaws of death, but everyone should read it. De Gaulle has no comparable war time stories.

Marguerite’s outings with Rabier are both a threat to Morland’s cell and am opportunity. Though frightened of each dreaded meeting with Rabier, Marguerite realises that she could play his game. He feeds her critical information without always realising it which she passes on to the Resistance.

Many photos of a 30-ish Duras suggest a good resemblance in face and petite stature to actress Mélanie Thierry (whom Finkiel directed in Je ne suis pas un salaud). She paces her period apartment, cigarette in hand, alternating between tears and contemplative stoicism with the occasional pounding of the typewriter.

But Finkiel seems so enthralled with the written word – or perhaps to Duras’s own directing style of voice-over narration – that he seems to be testing Iranian director Jafar Panahi’s maxim, ‘If we could tell a film, why make a film?’ And Duras herself writes, ‘words don’t describe what eyes have seen.’ But here, they too often do.

Too often the narration from the memoir substitutes for the physicality of Duras’s descriptions and for her cinematic dramatic accounts. Marguerite tells us, ‘it’s a period of fear – daily, awful, overwhelming fear.’ But Finkiel’s film is oddly devoid of fear or even suspense. He does dramatise the key scene in which Rabier invites Marguerite to a restaurant frequented by Nazis and her fear nearly gives away her Resistance friends who have taken seats undetected, waiting for their moment to assassinate Rabier. Not only do we feel no tension or fear, we do not even see Rabier’s ‘trembling hand’ which Marguerite notices.

There is even narration when it is unnecessary. Marguerite’s lament about the ‘age old waiting of women in war’ is redundant as there are already excellent dramatisations of three different women waiting in war: Marguerite; Madame Bordes, and, in one of the film’s most poignant scenes, Shulamit Adar’s Mrs Katz. She is washing mothballed clothes and ironing them for the return of her disabled daughter who was gassed in a camp the previous year.

Finkiel shows great skill in using the camera to express Marguerite’s feeling of being a disembodied soul, for example by using the reflection of mirrors to suggest she is looking at another person. There is a stunning shot of Robert on the beach where his still emaciated body is distorted like memory and broken up by the blazing sun and the sea, fragmenting before her eyes like their marriage, which was about to end.

But, curiously, Finkiel fails to capture the moral complexity of Marguerite’s war: her game with the married Rabier that could endanger her colleagues; her well-meaning lies to Madame Bordes; her affair with Dionys (Benjamin Biolay) Robert’s close friend; and her participation in the torture of a suspected informer to the German Secret Police. Though graphic, harrowing, revealing and all about pain, this ordeal is omitted from the film. Marguerite calls herself Thérèse, but she sees in the suspect the man who betrayed Robert and all the Jews. Thérèse is me’, she writes. ‘The person who tortures the informer is me.’ After obtaining the confession, Thérèse weeps. Pain manifests itself in many ways.

You can watch the film trailer here: