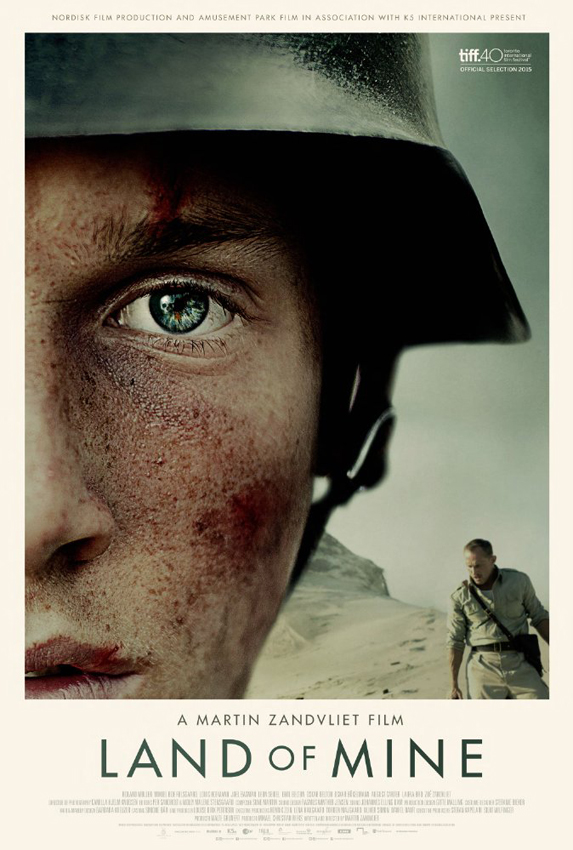

Joyce Glasser reviews Land of Mine (August 4, 2017) Cert 15, 99 mins

Martin Zandvliet’s (Applause) Land of Mine, is based on the true life Danish initiative to use German prisoners of war to clear German landmines in the aftermath of WWII. While those Germans who invaded Denmark in 1940 were the vanguard of Hitler’s mature, well-equipped and trained and well-fed forces, the POW’s who were forced to clear the mines after Germany’s surrender were the exact opposite. Most were boys between the ages of 13-18, conscripted by Hitler in a desperate attempt to replenish his troops. Based on real events, Martin Zandvliet’s (Applause) harrowing Land of Mine (Danish: Under sandet, literally, ‘Under the Sand’) is an emphatic moral quagmire. Nominated for an Academy Award in the Best Foreign Language Film category, it is also a film that shares Albert Camus’ interest in how human beings confront and live with their impending death as explored in his allegory of the France’s Nazi occupation, The Plague.

Denmark emerges from WWII darkened by five years of collaboration with the Nazis or hatred of their German occupiers. But what the Germans are leaving behind is equally dangerous: some 2 million land mines that the military planted on Denmark’s beaches between 1942 and 1944 as part of their ‘Atlantic Wall’ fortifications against an British and American invasion.

Denmark emerges from WWII darkened by five years of collaboration with the Nazis or hatred of their German occupiers. But what the Germans are leaving behind is equally dangerous: some 2 million land mines that the military planted on Denmark’s beaches between 1942 and 1944 as part of their ‘Atlantic Wall’ fortifications against an British and American invasion.

A Danish sergeant with a personal vendetta against the Germans Carl Leopold Rasmussen (Roland Møller) assaults two German POWs who get out of line. He is as brutal and frightening as were the German soldiers and the group of young POWs assigned to his command are at his mercy. Herded into trucks, the boys are driven to a white sandy beach with endless dunes. The setting looks like a holiday destination, not the place where so many will die. In the director’s statement Zandvliet tells us that this juxtaposition was essential to his vision. It was also essential to Camus’, who, in The Plague and, more famously, The Stranger (or Foreigner, or Outsider), drew on the discrepancy between the beauty of the sea in sunshine and the desolation of the human condition.

Rasmussen reacts, just slightly, to the news that none of the boys has had any experience with mines. He tells them that their task is to remove German landmines buried under the sand and provides rudimentary training. If they defuse six per hour, they will be home in three months. But that assumes they will survive three months, and the odds are against them. It is estimated that of 2,600 Germans forced to work in mine clearance, half were killed or seriously injured.

Rasmussen’s boss, Captain Ebbe (Mikkel Følsgaard), has warned the POWs not to expect any sympathy from the Danish people and from Rasmussen to the widow (Laura Bro) in a lone farmhouse on the beach, and crude American GIs, they are treated with contempt. Starving, (Denmark faced serious food shortages), the boys sneak out at night to steal food from the farmhouse larder, only to discover it was tainted with rat droppings. Realising they might all die, Ramussen forces the boys to vomit by drinking sea water. When the widow learns what happened, she is satisfied that she could do her bit for the war effort.

Zandvliet cuts from the tension of the mine sweeps on the dunes to the bunkhouse where he singles out a few of the boys with whom we build an emotional attachment. In the face of the cynical Helmut Morbach (Joel Basman) who reminds the boys that there will be nothing to return to, twins Ernest (Emil Belton) and Wilhelm (Leon Seidel) Lessner declare that they will become bricklayers to rebuild the country. Equally undaunted, Wilhelm Hahn (Leon Seidel), says he will work at his father’s factory. The boy who becomes the group’s natural leader and spokesman, Sebastian Schumer (Louis Hofmann), invents a device that would make the work easier, and Rasmussen, who is beginning to admire Sebastian’s courage, allows them to use it.

While the boys break our hearts with their vulnerability, Rasmussen’s contempt turns to pity as he gets to know them. He earns the wrath of his superiors by smuggling food back to the malnourished boys. When Wilhelm’s arms are blown off, and dies in hospital, Rasmussen tells the boys that he is recovering to keep up their morale. Schumer emerges as Camus’ existential hero as sustains hope in the face of despair and a world that really is uncaring. There is even a scene, the equivalent of the swim in the ocean in The Plague, where the boys and Rasmussen play football on the beach, suggesting our not only our ability, but our need to put aside our suffering and bleak future for a couple of hours of normalcy.

The gradual bond between Rasmussen and the boys is predictable, though Zandvliet tones down the sentimentality. When his beloved dog is blown up in an alleged safe zone, Rasmussen’s mood shifts and the boys bear the brunt of his grief. He forces them in a suicide march along the zone that they had declared safe. His humanity returns only when the suicidal Ernst saves the widow’s young daughter who has ventured onto the beach next to a mine. His heroism at the end appears so natural and in keeping with the character’s journey, that we accept it.

Since the story is told from the perspective of the innocent German boys who had nothing to do with planting the mines, it is difficult to sympathise with the Danish, particularly at the end when the promise that has kept the boys going is retracted. Still, with so much hardship and death caused by the Nazis, and the clearance cost so high, what country would ask its own citizens to risk their lives, and, in peacetime, be killed by German weapons?

Working largely with amateur actors (many of whom had to learn German dialects and class differences in speech), the cast is exemplary, while Louis Hofmann gives a breakthrough performance. What stays with you though is the cruelty of the mission – which was a violation of the Geneva Convention of 1929 as Zandvliet puts us there with the boys. And he never relinquishes the fear that the boys wake up with every day its harrowing hold on our emotions.

You can watch the film trailer here: