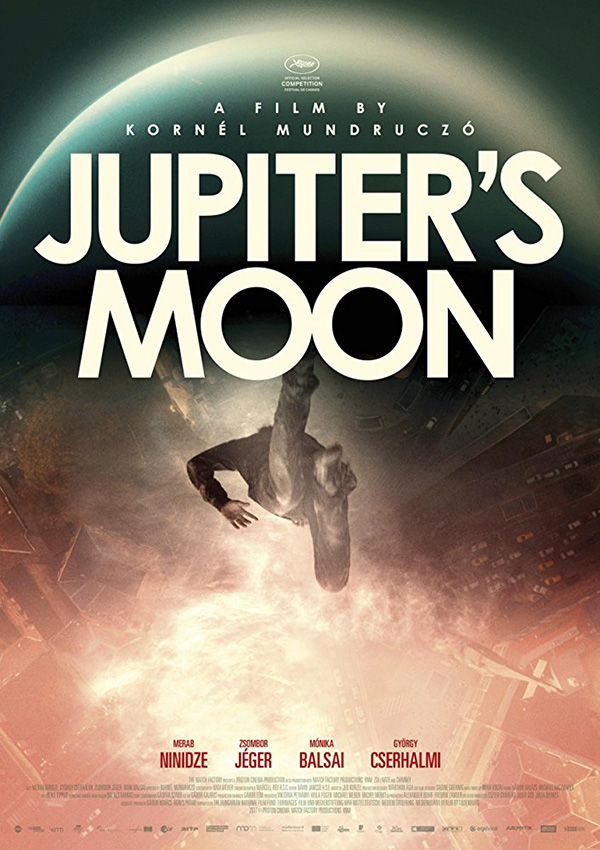

Joyce Glasser reviews Jupiter’s Moon (January 5, 2018) Cert. 15, 128 min.

Hungarian filmmaker Kornél Mundruczó’s follow-up to his powerful parable, White God is another visually stunning and inventive tour de force from Mundruczó and his cinematography Marcell Rév. While fans won’t want to miss Jupiter’s Moon, the single-minded metaphor of White God is this time confounded with a muddle of themes and genres, pulling the viewer in all directions.

The main direction to be looking in Jupiter’s Moon is up, and not just because of its title. In a captioned prologue we are told that one of the 4 largest of Jupiter’s 67 moons discovered by Galileo Galilei in 1610 is presumed to have a saltwater ocean under its icy surface, making life possible. The moon has been named Europa.

No prizes here for guessing that life on earth’s Europa, while not unspoilt, is equally precarious. Europe is a battle ground between the police state represented by trigger-happy border cop László (Gyӧrgy Cserhalmi) who is charged with deterring the invasion of the barbarians, and the tide of refugees represented by Syrian teenager Aryan (Zsombor Jéger) fleeing from Homs through Serbia into Hungary.

No prizes here for guessing that life on earth’s Europa, while not unspoilt, is equally precarious. Europe is a battle ground between the police state represented by trigger-happy border cop László (Gyӧrgy Cserhalmi) who is charged with deterring the invasion of the barbarians, and the tide of refugees represented by Syrian teenager Aryan (Zsombor Jéger) fleeing from Homs through Serbia into Hungary.

After our science lesson – although it should be noted that Galileo spent the end of his life under house arrest for challenging the backward authorities – we get a thriller. Aryan and his father are suffocating in a crowded freight car reminiscent of those delivering Jews and other alleged ‘impure breeds’ to the concentration camps. They are due to board a boat in the dead of night, but are detected. Aryan escapes from the border guards, becoming separated from his father in the process. He is eventually trapped in the woods by László, a man whose face looks like the craters of the moon, and though Aryan is unarmed and freezes in his tracks, the policeman shoots him.

Despite being hit a symbolic three times, Aryan does not dies. Instead, he slowly levitates above the earth, an unlikely angel in his blue jeans and trainers.

As in White God, Mundruczó is not interested in the subtly of his allegories because he knows that his visual treatment of his story, and his trump card for Aryan, will provide more than enough distraction. In fact, he, and co-writer Kata Wéber, provide a bit too much.

Aryan’s life now becomes linked with an unlikely father figure, Gabor Stern (Merab Ninidze). Stern is a Hungarian doctor who operates a scam between the refugee camp, the city’s hospital and the homes of wealthy patients desperate for miracles. In a back-story reminiscent of the doctor’s in this year’s The Killing of a Sacred Deer, Stern is threatened with a lawsuit for botching an operation while under the influence of alcohol. Stern accepts bribes from the refugees to smuggle them out of the camp to the hospital. There, his besotted girlfriend, Vera (Mónika Balsai), a nurse in the hospital, facilitates their disappearance.

László is well aware of this disappearing act and his strained relationship with Stern remains civil only because he is not above supplementing his policeman’s pay for losing a bit of paperwork. However, when both men become touched by the angel Aryan, they become deadly adversaries. László has become haunted by the vision in the woods, and the idea that he might be the Pontius Pilate to Aryan’s Christ-like rising from the dead.

While Stern taunts László about his possible damnation, he is out to exploit the boy, (with whom he speaks in impressive, if audibly difficult to understand English), taking Aryan’s Marvel Superhero attribute almost for granted. Stern, who is one of those likeable amoral characters who exploits a rotten system, becomes increasingly less likeable, until he is redeemed – although much more dramatically than Lili’s father in White God.

After marveling at Aryan’s powers, Stern’s wealthiest and most desperate patients are willing to stuff cash in Stern’s wide hands. Stern is no Fagan however, and shares the spoils with his increasingly repulsed sidekick who is still hoping to find his father and will need cash. These scenes would have been even more effective, however, if we understood the nature of Aryan’s flight, as in one home, he causes destruction in a kind of whirlwind, while in others his flight is silent and serene.

In the second half of the film Aryan and Stern go on the run after Aryan becomes implicated in a terroristic attack on the underground. Aryan and his father are now wanted men and Stern is an accessory when he is betrayed by a hospital worker.

The jihadi sub-plot is just one of many strands in this ambitious film that only serve to remind us that more often is less. Already the idea of a boy threatened with barbed wire fences being able to fly to freedom, is rife with possibilities. Some viewers might know of French writer Marcel Aymé’s parable, The Man Who Walked through Walls, a fantasy of escape which, against its background of occupied Paris in 1943, becomes darker than the comic-farce screen adaptations of 1951 and 1959 suggest.

There is also the idea of the Syrian ‘illegal aliens’ having something in common with aliens of another sort, particularly given the film’s title. This was the case with director Neill Blomkamp’s Sci-Fi metaphorical masterpiece of xenophobia and social segregation in South Africa, District 9. That was also the story of a father and son who encounter a fascist regime when trying to escape from an alien camp. While the bureaucrat who undergoes a redemptive transformation in District 9 is one of the great characters of the noughties, brilliantly played by the charismatic Sharlto Copley, Stern is a far less interesting character, played by a less charismatic actor.

But before you can even start to speculate on these literary and film references, you have to confront the big themes of religious allegory against Europe’s increasing secularisation; an overcrowded and decadent society’s corruption and loss of humanity; redemption (both doctor and cop); father-son relationships; self-sacrifice – and the idea that life on earth needs more than water to be worth living.

You can watch the film trailer here: