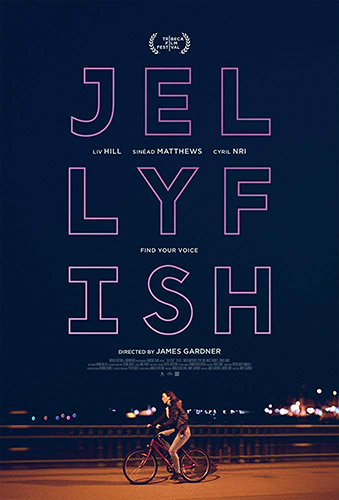

Joyce Glasser reviews Jellyfish (February 15, 2019), Cert. 15, 101 min.

James Gardner heralds from Hereford, but run-down seaside resorts are so much more poetic, dreamlike and cinematic, and few resorts more so than Margate. Margate is the birthplace of Tracey Emin; home of the Turner Gallery; setting for the amusement park, Dreamland and on its cheerless seafront T. S. Eliot dreamt up The Waste Land.

For his feature film debut Gardner, who is a graduate of the UK’s National Film and Television School, follows a British tradition of combining a kitchen-sick drama with a coming-age-story to show how hard it is for a deprived teenager to escape the short straw that life drew for her. If Gardner milks the misery and hardship of his teenage protagonist for all it is worth, newcomer Liv Hill keeps us watching, as does a little twist that confounds expectations and the attendant sentimentality.

For his feature film debut Gardner, who is a graduate of the UK’s National Film and Television School, follows a British tradition of combining a kitchen-sick drama with a coming-age-story to show how hard it is for a deprived teenager to escape the short straw that life drew for her. If Gardner milks the misery and hardship of his teenage protagonist for all it is worth, newcomer Liv Hill keeps us watching, as does a little twist that confounds expectations and the attendant sentimentality.

Even by the standards of social-realist portraits of the lower classes, teenager carer Sarah Taylor (Hill) has it rough. We learn that after Sarah was farmed out to social care when her bipolar mother, Karen (Sinead Matthews) was deemed unfit, Sarah made a deal with her mother. Sarah will take care of her mother and her two adorable twin siblings (Henry Lile and Jemima Newman), and work part-time to supplement their benefits. If you are hoping Sarah’s job offers potential, watch her dusting the glass at a sleazy games arcade and giving hand jobs in the car park to a couple of unemployable fat slobs who are the only customers.

In exchange for Sarah’s caring responsibilities, all Karen has to do is show up once a week at the benefits office to get her housing benefits paid.

When even that proves too much for Karen, who, in addition to being a manic-depressive, is an alcoholic, and when Sarah loses her job for her ‘on the side’ activities, the resourceful 15-year-old goes out on a limb. She uses the oldest trick in the book to extract money from a slimy married estate agent who picks her up at a bar and invites her to his flat. This extended scene is one of the highlights of the film, but is far from upbeat. In a rather less believable scene, Sarah entrusts the money to her mother, now enjoying one of her highs on a family outing to Dreamland, who promises to use it to pay the rent.

Desperate not to lose her home – depressing and rundown as it is – Sarah gets her job back by agreeing to work full time. But her hypocritical, heinous boss (Angus Barnett) is still not satisfied. He extracts a price too high, even for Sarah.

While Sarah drops her siblings off at their school every morning and collects them, Sarah’s school seems oddly confined to one performing arts class, although she is only 15. She takes out her frustration and low self-esteem on her class mates, mocking their amateur song and dance acts and treats her teacher Adam (Cyril Nri) with little respect.

Still, Adam is Sarah’s only rock and the only one who cares about her: within limits. Sensing he cannot expect her to participate in team activities, and that her foul mouthed tirades might be redirected onto the stage, he suggests that she go to the library and, on their computers, listen to some stand up comics. He provides her with a list which, at Sarah’s request, includes a few women. But Sarah only gets as far as Frankie Boyle. She can identify with his language and subject matter. Sarah finds a new meaning in her lonely, empty life, jotting down lines in a notebook, presumably using the depravity of Margate as her springboard. When we see her laughing out loud, we can imagine some of the lines are pretty funny. We have to wait a long time, though to hear them, and never really do.

The problem is not so much the clichés of Sarah’s existence, but that Gardner does not give his heroine enough opportunity to subvert them. The UK is full of carers and neglected children, but some of the misery seems contrived and the relationship between Sarah’s prospects and the town’s is put in focus. The camera shifts away from a rape scene, for instance, to shoot the empty, run-down streets of Margate, as if to underscore the relationship between a teenager’s fate and the town’s economic prospects.

Gardner does understand the value of nuance, particularly in Sarah’s relationship with her mother and Adam. That said, Matthews’ performance is too full-on, and even when Karen can get out of bed, she is so annoying, wasted and untrustworthy that it is hard to imagine Sarah having faith in her. The relationship with Adam is more convincing. Sarah’s offensive conduct and insults would prove too much for anyone, and Adam finally does give up on her. Sympathetic and perceptive as Adam is, Sarah’s life is so dysfunctional that even he cannot possibly understand where she is coming from – until she jumps on stage and tells all of Margate what it should know.

The biggest surprise is that there is not a competition that Sarah wins, as you would expect. Gardner shows restraint, making us wait until the very last moment to see if Sarah will latch on to comedy as a possible way out. Perhaps Gardner shows too much restraint as we are given too short a glimpse of her potential before reality sinks in.

Still Gardner keeps us watching with no longeurs. Thanks to some touching moments that never lapse into sentimentality, and Hill’s indomitable performance, we are rooting for Sarah all the way.

You can watch the film trailer here: