Joyce Glasser reviews Il Postino (Il Postino: The Postman) (re-issue: October 15, 2018), Cert. U. 108 min.

The aim of re-issues is to introduce old and older films to new audiences to ensure continuity, shared cultural references and cine-literacy. But re-issues should also encourage a reassessment of a film, not only in terms of whether it stands the test of time, but in terms of the context and circumstances in which the film was made. Michael Radford and Massimo Troisi’s Il Postino: The Postman is, in all respects, an ideal and important re-issue. The film was made for $3 million and took $21 million at the box office. It was nominated for all the major Academy Awards – Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor and Best Adapted Screenplay – unheard of for a subtitled film in a foreign language. It was the first Italian film to be nominated for Best Picture by the American Academy.

Today, the focus is on Harvey Weinstein as a predatory misogynist, but without the support of Miramax in the early 1990s, Il Postino

’s recognition, box office and legacy might have been very different. And it is fair to wager that it would not have won the Academy Award for Best Original Dramatic Score and a BAFTA for Best Film Music. It was Harvey Weinstein’s idea to promote the film by incorporating celebrity readings of the Pablo Neruda love poems into Luis Bacalov’s music.

And then there is the tragic ending, both in the film and in real life that contributed to the bitter-sweet legend that Il Postino had become. Troisi, who died on June 4, 1994, just before the end of principal photography, postponed having a heart transplant until after the movie, which he saw as his crossover opportunity. Not only does he star opposite superstar Philippe Noiret, but he shares scriptwriter credit with Radford (and three others) and shares a director credit. He apparently told Radford, ‘I’m an actor. My emotions come from my heart. Who am I going to be with someone else’s heart?’

Massimo Troisi was a huge celebrity comedian in Italy, but unknown in most of Europe and in America. His posthumous Best Actor nomination was a source of pride to Italians who flocked to see the film, and it created interest in the rest of the world. Producer Mario Cecchi Gori, died during production, seven months before Troisi; and his Best Picture nomination was also posthumous.

But the box office and the awards were not sympathy votes. Il Postino is an unapologetically romantic film, with humour, tears, beautiful scenery (the film was shot primarily on the island of Procida in the Gulf of Naples), a poetry-infused script, winning performances from Troisi and Noiret – and a loose historic and biographical base.

Mario (Troisi) is a poor, uneducated fisherman’s son who fears he is allergic to fishing boats. ‘Every time I go on that boat I get a cold,’ he complains to his taciturn father. In an opening scene he and his father are at the breakfast table in almost total silence. When they talk you might think they are mentally challenged, but there is no verbal tradition on the island, no library and not much opportunity for intellectual discussions. There are local politicians, however, and one is campaigning about the water shortage. Mario informs his father there is no running water.

Mario’s father tells him he can go to American or Japan if he does not want to fish, but he has to get a job to get anywhere.

The job proves his making, and perhaps his undoing. He becomes the personal postman to visiting celebrity Pablo Neruda (Noiret). While Mario has never read a poem in his life, he has watched the newsreels about Neruda’s exile and particularly about how his love poems fill stadiums with adoring women. Mario is a tall, good looking, grown man and wants to attract women. The answer is to become a poet.

While the film is set in 1950, Neruda did stay in a villa owned by Italian historian Edwin Cerio on the island of Capri in 1952. This stay was fictionalized by Antonio Skármeta in his 1985 novel Ardiente paciencia, set in Neruda’s house in Isla Negra in Chile. The collaboration between Radford and Troisi was loosely based on the book.

The bulk of the film, and the most enjoyable part, are the meetings between the ignorant, tongue-tied, awe-struck postman and the famous poet that lead to Mario’s literary awakening. He watches Neruda dancing with ‘his wife’ with longing. His ‘wife’ might have been his carer-turned-lover and travelling companion, Chilean singer Matilde Urrutia, who he would eventually marry.

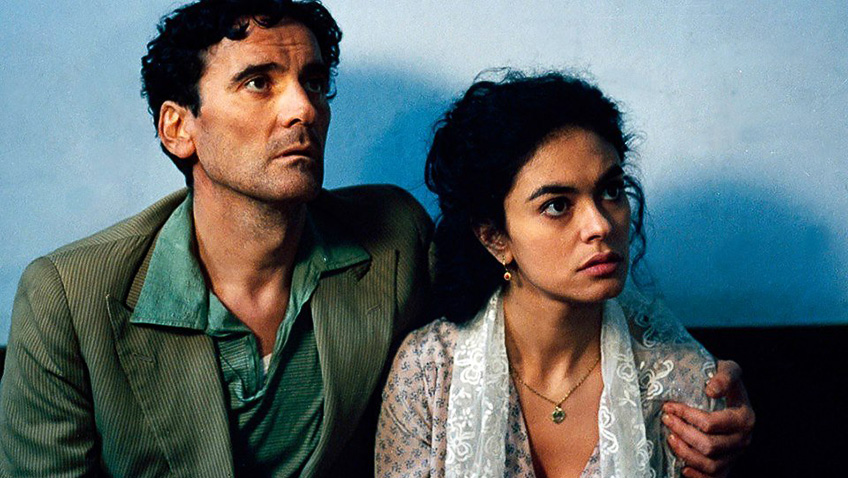

When Mario first meets the beautiful Beatrice Russo (Maria Grazia Cucinotta), the restaurant owner’s sexy niece, she takes his order, but he is unable to speak to her. The scenes in which Mario asks for Neruda’s advice in matters of the heart are sweet as pie, particularly when he introduces Mario to Dante, explaining the significance of his love interest’s name.

Mario starts wooing Beatrice with poetry, largely taken from Neruda’s writings, and it does the job. Perhaps a bit too well. For Beatrice’s protective aunt is having none of it, reading in between the lines of the poems. But love conquers all and Mario and Beatrice marry and have a son named after the poet.

The final third of the film becomes more of a problem in watching the re-issue. Neruda is too busy back in Chile after being pardoned to stay in touch, and there’s a long sentimental section where Mario records sounds of the island to send to him. While Troisi was ill throughout the shoot (he collapsed on the third day of filming), toward the end, he was so weak that body doubles were used much of the time. The scene in which we learn of Beatrice’s pregnancy is nothing short of awkward. She is on her bed alone talking to herself, as Troisi was absent. Mario borrowed more than poetry from his hero; he becomes a communist and he is killed at a demonstration where he intends to read a poem he had written. This scene is so sudden and hastily put together that it prompts a jolted confusion rather than tears.

But nearly a quarter of a century ago, Harvey Weinstein told Michael Radford, ‘I’m going to sell poetry to the American public’ and he did just that. The poetry still casts a spell and stands the test of time.

You can watch the film trailer here: