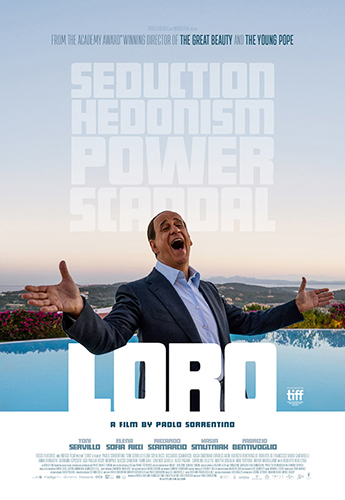

Joyce Glasser reviews Loro (April 19, 2019), Cert. 18, 150 min.

Around the time Italian writer/director director Paolo Sorrentino’s 2008 film Il Divo (The Celebrity) was being awarded the Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival, Silvio Berlusconi was being sworn in for his third term as Prime Minister of Italy at the age of 72. Loro, Sorrentino’s biopic of the controversial tycoon and politician, is a visual wonder, pushing the boundaries of Luca Bigazzi’s gorgeous cinematography and Stefania Cella’s dazzling production design – both of whom worked on Sorrentino’s Academy Award winning La Grande Bellezza (The Great Beauty). In his last film, Youth, Sorrentino’s trademark style overwhelmed the shaky substance, but in Loro

the two are inseparable, with the sleaziness, opulence, moral bankruptcy and spiritual and intellectual emptiness conveyed visually and sustained by the dialogue and dramatic narrative. It’s just a shame that the subtitles fly by so quickly with the wordy dialogue that the visuals are sacrificed in part to the subtitles.

Starring Sorrentino’s muse Toni Servillo, Loro

Starring Sorrentino’s muse Toni Servillo, Loro is, in many ways, a sequel to Il Divo which begins with Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti, played by Servillo, reflecting on how he has outlived all his detractors in the turbulent world of Italian politics. Berlusconi might have been thinking the same thing, having been found guilty of only 1 of 32 serious charges brought against him in the Italian courts.

Loro could also have been entitled Il Divo, but Silvio (Servillo), who succeeded Andreotti as Prime Minister, does not appear for the hour of the 150 minute film as though keeping his audiences waiting as divos do.

In a kind of prologue, we do, however, get a glimpse of his sprawling, luxurious Sardinian hideaway that will be the main setting of the film. It is eerily empty save for the droning of a television (Berlusconi made a fortune from a television network producing cheesy, popular programming) and a sheep that wanders in from the seaside pasture. This featured sheep could be a reference to Berlusconi’s 2017 advertisement for a vegetarian Easter and his adoption of five adorable lambs.

What we have leading up to Silvio’s entry contributes to the nonetheless surprising 18 certificate. Sergio Morra (Riccardo Scamarcio) is an ambitious, lowlife from Taranto who makes his living trafficking young women to men of influence in exchange for licences and money. Bribery is not beneath him and his equally unscrupulous partner Tamara (Euridice Axen).

Although Silvio (and his Forza Italia party) is in semi-retirement on his island retreat, he remains arguably the most influential man in Italy and no one believes his political career is over. Indeed, he is already launching his comeback which sees him gain a third term on 8 May 2008 (until 16 November 2011).

Sergio with his eyes set on the prize has moved to Rome where, with Silvio’s (referred to as ‘lui, or ‘him) beautiful, confident mistress Kira (Kasia Smutniak) builds a bevy of young, long-haired women and nymphet’s fit for the king. He risks everything on renting a mansion within binocular distance of Silvio’s estate and parading the women like sirens on a yacht hoping to attract Silvio’s attention. As if to recreate the moral vacuum and boredom of Sergio’s exploits, Sorrentino lingers on the poolside parties at the rented villa for so long that he tests the viewers’ patience. Finally, Silvio appears, ironically and humorously, as our saviour. But Sergio misreads the situation and we can see the increasing concern on his face as he fails to be noticed.

Silvio is 70 and, reeling from a previous narrow defeat, is busy plotting his comeback with an old friend, Ennio Doris (Servillo again) who suggests luring six senators to switch sides. Having had years of experience with casting couches for his myriad game and reality TV shows and soap operas, Silvio is always ready to offer someone’s mistress or daughter a television opportunity in exchange for backing.

Silvio’s only rival for Party Leadership is former minister Santino Recchia (Fabrizio Bentivoglio) who is taking advantage of Silvio’s relative absence in Rome to take over. He is undone by a pair of women. Sergio’s partner Tamara seduces Recchia and then blackmails him, prompting Recchia to seek help from, ironically, Silvio himself. But by now Silvio has learnt of Recchia’s plan through a woman who has betrayed Recchia’s confidence, and ‘lui’ shows the snivelling hypocrite no mercy.

Sergio is also unaware that Silvio’s marriage to Veronica Lario (Elena Sofia Ricci), the mother of three of his children, is on the rocks, primarily due to his philandering, and surprisingly, he still loves her. When Silvio, with a kind of ghoulish smile on his mask-like face, stiffened from plastic surgery, finally makes his appearance in the film, Servillo and Ricci dominate the screen and, despite some longuers in this part, too, they are an electrifying duo.

The tension now comes from Silvio’s efforts to win back Veronica and we see another side to Silvio as the two rekindle their early romance. When Veronica goes off on a trip to Cambodia, however, Silvio invites Sergio’s girls over to his villa for a Feliniesque party. But the party girls are bored and the only man, Silvio, is attracted only by a short-haired, independent-minded student named Stella (Alice Pagani) who reminds ‘lui’ that she is underage and he is old enough to be her grandfather.

Servillo’s nuanced and psychologically astute portrayal captures Silvio superbly, making the film less a critique or satire of the leader than a portrait. Unrepentant, unashamed and transparent, Servillo shows us the salesman who began his career selling properties to upper middle class families, then cable television stations to the properties while selling the advertising behind the programmes.

There is a marvellous scene in which, whimsically, Silvio wants to see if he still has his what it takes. He chooses at random a name from the phone book and tries to sell a new home that has not been built yet to the woman who answers. The woman tells him he sounds like a swindler, but rather than retreating in embarrassment, Silvio accepts the comment with good humour and continues to persuade her.

Each part of the film, which was significantly abridged from the much longer Italian version, shown as two separate films, ends in symbolism. In the first, Sergio’s babes run around Rome as a garbage truck smashes into some antique ruins in an attempt to avoid crushing a rat. The symbolism at the end is only a little more subtle, but it is powerful; like a work of art. In the ruins of the 2009 L’Aquila earthquake, workers salvage a statue of Christ that is placed on the side of a mound of rubble.

Exhausted fire-fighters sit at the foot of the mound like soldiers or followers in in paintings of the descent from the cross. Many Italians will remember Berlusconi’s television broadcasts of the period, urging victims to treat the event as a holiday paid for by the government, which would be providing free food and accommodation in holiday camps until the area was rebuilt.

You can watch the film trailer here: