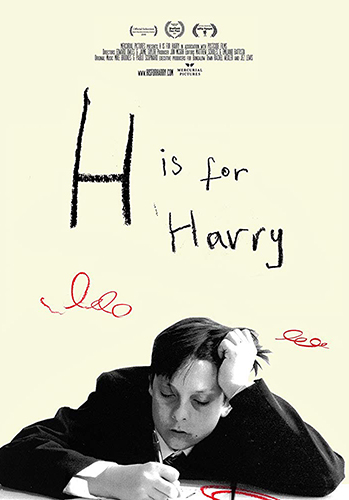

Joyce Glasser reviews H is for Harry (March 7, 2019), Cert. 12A, 86 min.

Let’s hope that the cinema is the right outlet for this heart-breaking documentary about the correlation between education and income and the challenges of educating children with special needs. H is for Harry deserves a wide audience, but in focusing on a boy from a low income, single parent household with behavioural problems, in addition to educational special needs, it might be juggling too many variables, while raising more questions than it answers.

Directors Edward Owles and Jaime Taylor’s thought-provoking and absorbing behind the scenes exploration is not really, as the production notes suggest, a coming-of-age story about a charismatic 11-year-old. Rather, it is the story of a boy and his father who are hoping that the Reach Academy in Feltham can save the boy ‘from a life of illiteracy and poverty’.

Directors Edward Owles and Jaime Taylor’s thought-provoking and absorbing behind the scenes exploration is not really, as the production notes suggest, a coming-of-age story about a charismatic 11-year-old. Rather, it is the story of a boy and his father who are hoping that the Reach Academy in Feltham can save the boy ‘from a life of illiteracy and poverty’.

At the opening assembly the students are told, “we are all on the path to university”, but Harry and his teachers have no idea how difficult that path will prove to be. All the school’s motivational pitches can frighten the students they do not inspire. For this is the story of how one of great London’s most progressive schools, and the first all-through school to be rated outstanding by Ofsted is no match for an intergenerational cycle of illiteracy, defeat and low expectations.

Harry is 11 when he starts at Reach Academy in Feltham, and its dedicated teachers, including a recent graduate named Sophie, set about preparing him for GCSEs. The Academy aims to ensure that regardless of the student’s individual starting point, he or she will achieve the grades that would enable them to go to university. Toward that end, we see Harry and another boy have one-on-one sessions with the ever-patient Sophie, and not all of their sessions are focused on the curriculum. Cake is brought out to celebrate the day when Harry has sufficiently caught up to join the mainstream students. But can he sustain his progress?

The Reach Academy seems to be modelling itself after the Knowledge is Power programme, established in the USA in 1995 and aimed at promising minority students. They are required to sign a commitment of excellence agreement and to agree to certain rules designed to help the student succeed and go to college.

For Harry, Reach Academy is a new beginning, and for his father Grant, it is the last chance for his son to break through a cycle of educational failure. ‘It’s just repeat, repeat, repeat,’ he explains. ‘My dad’s had it; I had it and now my son’s gonna have it.’

It is not just Grant’s family. In the film Harry is emblematic of thousands of other Harrys. And they have to face the statistics (the film provides several):

- 1 in 5 children in England cannot read well by the age of 13

- 4.1 million British children live in poverty

- 1 in 8 disadvantaged children in the UK don’t own a single book.

- Whereas approximately 60% of the overall population secure at least 5 GCSE grades at the government’s expected standard, only 26% of white working class boys on free school meals achieve this level

While you cannot take a step in the Academy without encountering a motivational slogan, Grant’s expectations are realistic. He just wants his son to be able to read and write. Harry’s are not much higher. When Sophie asks, ‘what are you going to be doing when you’re 25, Harry?’ he replies, ‘trying to stay alive.’

But what makes this story so sad is that after expectations are raised Harry dares to hope that he can make his dad proud and join the mainstream. ‘When I’m older, I don’t want to be the person who’s left out, living on the streets, basically the aim for me is like to have a better life than my dad. He was like worser than me always getting kicked out of every single school…’

Your heart goes out to the 11-year-old who says this, but, given its importance in the film, sub-titles might have been helpful as Harry is not always audible and articulate.

Harry is not alone in coming into the school in need of extra time with the staff to catch up. As a teacher in the film says, ‘We have had children come to us this year in Year 7 [Harry’s age] who can’t tell the time; can’t tie their own shoelaces and struggle to spell their own name.’ The baggage the children bring to class is varied, but the teachers (at least in front of the cameras) are kind, patient and caring.

Harry learns to read and write but writing essays on Shakespeare is another matter. He is easily distracted and chastised repeatedly for disciplinary problems, like calling a girl in his class ‘ugly’. Grant is frustrated that he is unable to help his son with his school work, and Harry is draining the school’s resources. The teachers decide (although we are not privy to the decision making process) that Harry might be better off in a specialist school.

There is a very moving scene toward the end of the film where Harry is serving as a mentor to very young pupils and his rapport with the children is remarkable. We see what a sociable, kind-hearted, guileless and vulnerable boy he can be and we care deeply about his fate. Harry might be emblematic of white, secondary students from a poor social class, but the film succeeds so well in making us a part of Harry’s life and making us care about the outcome of this experiment, that it is frustrating not to know more when the film ends rather suddenly.

You can watch the film trailer here: