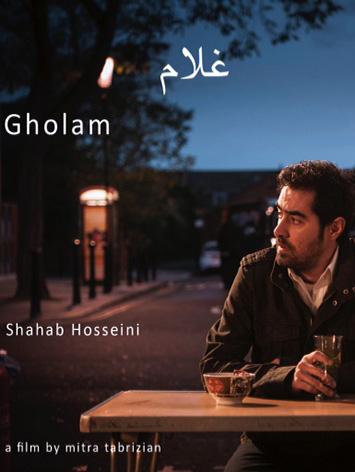

Joyce Glasser reviews Gholam (March 23, 2018) Cert 15, 94 min.

Every country has own its dark, brooding actors, and if Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift and James Dean remain the gold standard, contenders like Casey Affleck (Manchester by the Sea) are not far behind. In France, Jeanne Moreau, Jean Gabin and Yves Montand remain hard to beat, but actors like François Cluzet (Scribe) are close behind, while in the UK, Tom Hardy stands out.

But these silent, contemplative types with dark back stories now have serious competition from Iranian actor Shahab Hosseini, a favourite of Academy Award winning director Asghar Farhadi (About Elly). In Gholam, British-Iranian writer-director Mitra Tabrizian has given Hosseini a superb platform on which to tap into his brooding talent, while examining the plight of Iranian refugees in London.

For most of the film we follow refugee Gholam (Hosseini) during his quiet, monotonous life as a works two jobs and eats in silence every day at his uncle’s restaurant, always refusing their insincere offer of a free meal. His routine is punctuated by occasional incidents and characters that gradually add to our scant knowledge of the protagonist’s enigmatic character and circumstances.

For most of the film we follow refugee Gholam (Hosseini) during his quiet, monotonous life as a works two jobs and eats in silence every day at his uncle’s restaurant, always refusing their insincere offer of a free meal. His routine is punctuated by occasional incidents and characters that gradually add to our scant knowledge of the protagonist’s enigmatic character and circumstances.

Gholam, in his 30’s, is working as a cab driver, but you can tell from the first scene, that it is out of necessity, not choice. The language barrier might not be preventing Gholam from chatting with his customers; when we see him with fellow Iranians in London we realise he is the silent type.

Gholam prefers his job at a local garage, where he is content to drink tea with its intellectual owner (Amerjit Deu) and listen to his stories of life in the old country. The garage owner is representative of those who had to give up part of their identity, if not their professions, to survive in their adoptive country.

But, like so many immigrants on zero hour contracts and no support systems, Gholam needs to work two jobs, and then, only to afford food and the rent on a shabby, depressing bed-sit.

We first see Gholam at night, and as his taxi customers do, through his rear view mirror. Irritated at the businessman gabbing on his phone in the backseat, he stops the cab short of the man’s destination and when the man protests, he speeds off without asking for the fare. If you are not reminded of Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, it could be that the low key soundtrack and lack of narration makes the comparison less obvious. Both Travis Bickle and Gholam are depressed and lonely ex-military men who live alone in decrepit quarters and share an eruptive, brooding personality and a longing to reach out to other alienated souls. Gholam, however is in another country.

Gholam gets into trouble with his boss when the police find him asleep in the cab and much later in the film, is sacked for pursuing two thugs who refuse to pay the full fare. In chasing after the hoodlums, his agility, courage and strength provide us with a rare glimpse of why Gholam is being pursued by a cagey political group in exile. Its grey-bearded leader (Nasser Memarzia) recognises Gholam in his uncle’s restaurant and continually tries to bribe him into lending his latent combat skills to their cause – of which we know and learn nothing.

Gholam’s young cousin, Arash (Armin Karima), an aspiring rapper, is, unlike Gholam an assimilated Iranian, able to find his place in England without forsaking his Iranian background. He is intrigued by these rumours of his unassuming uncle’s heroism, but Gholam refuses to be drawn out.

Gholam’s act of charity and kindness to a black woman whom he meets in the launderette is clearly Tabrizian’s attempt to show another facet of Gholam, one that we only otherwise see when he speaks to his anguished mother on the phone. But, unlike Travis Bickle’s attempt to dissuade a young prostitute from a life on the street, the relationship here is too transparent and turns a bit sugary.

Tabrizian’s script, based on an idea by Cyrus Massoudi, is a sobering, authentic and unsentimentalised look at the immigrant experience, and a man with no future, who is unable to assimilate, but uncomfortable with his immigrant community. This portrait is greatly enhanced by Dewald Aukema‘s atmospheric cinematography that binds Gholam to the dreary night that offers no repose.

Gholam is also a frustrating experience, particularly in dealing with the sub-plots about Gholam’s past. While it is refreshing to be allowed to use one’s imagination rather than being lectured, or spoon fed, we still need the clues to put the pieces together and Gholam is restrained to a fault.

As a film, Gholam has great potential, much of which is realised. As a character, Gholam has all the makings of a memorable romantic hero, but audiences cannot be sustained by brooding alone.

You can watch the film trailer here: