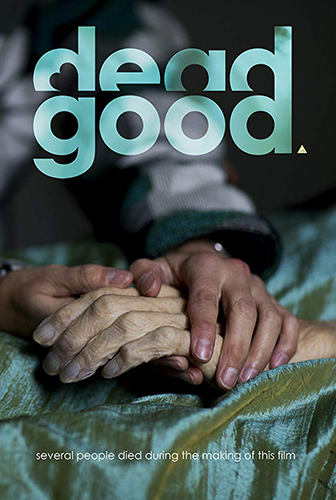

Joyce Glasser reviews Dead Good (May 10, 2019), Cert. PG, 78 min.

Documentaries about death are customarily relegated to television, but Dead Good’s lack of sensationalism could preclude it from something like the BBC’s Most Extraordinary Rituals series. There, the death ritual called Ma’Nene, practised in parts of Indonesia, involves exhuming the body of a loved one after designated periods of time for a reunion. Nowadays selfies with the corpse are shared with distant friends and family so that they can feel part of the ancient ritual. Documentary filmmaker Rehana Rose’s film is more useful and thought-provoking to western audiences, in particular, baby boomers dealing with the death of parents and their own deaths as well.

When Rose had to deal with the deaths of three people close to her in short succession she was struck with how little she (and those around her) knew about their rights and choices for burying/cremating and mourning a loved one. Death has become de-personalised and the corporatisation of death means that relatives distance themselves from the whole process. Funeral companies calling themselves ‘homes’ or ‘parlours’ (a telling euphemism) have an interest in encouraging this distance and keeping the ceremony a complex, regulated mystery best left to the experts.

When Rose had to deal with the deaths of three people close to her in short succession she was struck with how little she (and those around her) knew about their rights and choices for burying/cremating and mourning a loved one. Death has become de-personalised and the corporatisation of death means that relatives distance themselves from the whole process. Funeral companies calling themselves ‘homes’ or ‘parlours’ (a telling euphemism) have an interest in encouraging this distance and keeping the ceremony a complex, regulated mystery best left to the experts.

Rose began investigating alternative scenarios and discovered a group of women who are ‘giving death back to the people’ by encouraging people to take back ownership of their loved one’s passing and become involved in the process. The benefits are clear from the three groups of mourners we follow in the film.

During her research, Rose also realised that the funeral business is largely male orientated but the progressive death movement seems dominated by women. It might be a coincidence, but out of 10 funeral directors Rose approached only two agreed to participate in the film, and both are women.

Funeral director Cara tells us that she began working in the funeral business in 1998 but did not like the corporate environment and became a freelance embalmer. She realised that embalming was an unnecessary and invasive procedure as the process involves pumping in embalming fluid and pumping out body fluid just so the corpse can be put on show for a short time. After an unsatisfactory experience with a personal bereavement, she set up her own Sussex business in a homey, quirky space where family are encouraged to wash and prepare the body of their loved one and spend time with him/her in that period of limbo between death and the funeral.

The people who come to these niche funeral directors do not want the standard package funeral. This rejection stems from their respect for the deceased who, they feel, would not want this packaged funeral. The new breed of funeral directors pay house calls in ordinary, informal attire and chat with the bereaved like one of the family, quietly learning about the family as well as about the deceased.

In a gentle, slow observational style, Rose shows us three alternative funerals (one a cremation) customised to fit the personality of the deceased and in accordance with the feelings (and financial means) of the bereaved.

Two sisters, mourning the loss of their mother, a theatre director, recognise that she was a free spirited, anti-establishment person who would not have chosen a traditional service. When the coffin is about to be cremated, a red curtain closes, to symbolise the final act of their mother’s life. They want the audience to applaud – as audiences would, to show their appreciation for the person who has performed for them.

Richard’s family and Paul, an ex-lover of Richard, sit around the table paying tribute to Richard, who died in a homeless hostel. The memorial service does not ignore or put a spin on his troubled life (he had a psychology degree from university and a solid career, but ended up in residential rehab 18 months before his death), but the gathering focuses on the positives and on their memories.

Colin’s partner tells us that Colin was always in such good health that even when he was diagnosed with terminal cancer at no time would he admit he was going to die. His death was a shock to his partner as it came so fast. Colin was an environmentalist and a non-traditional person, so Peter a laid-back, straight talking Parish priest in layman’s clothing was the right person to lead the green celebration of Colin’s life. Peter believes that undertakers are now more humane and are increasingly less likely to stand as a wall between family and deceased. How typical in the sylvan setting of Colin’s hands-on burial that Martin Donnelly’s Green Man plays in the background.

That Dead Good deals with issues you do not expect to confront in a public cinema is perhaps proof of Rose’s thesis and of the need to unmask the mystery. After all, if only two things are certain, death and taxes, death is a universal theme that we will all face, and no doubt face many times in our lives.

You can watch the film trailer here: