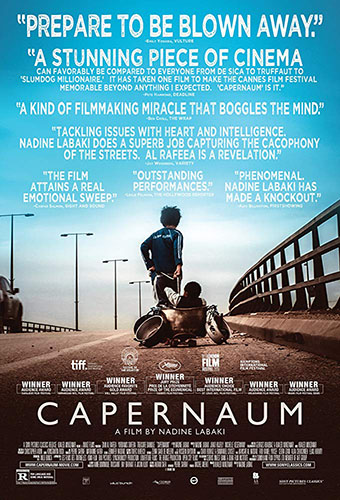

Joyce Glasser reviews Capernaum (Capharnaüm) (February 22, 2019), Cert. 15, 126 min.

The BAFTA’s have a Rising Star Award for British actors, but what we really need is an international award to recognise the astonishing performances from non-British newcomers – and non-actors. In 2017 little Sunny Pawar stole the show from BAFTA winner Dev Patel in Lion, but was not even nominated. It is safe to predict that the two clear winners for 2019 would both to be found in writer/director Nadine Labaki’s (Where do we go now?, Caramel) Capernaum, a remarkable social-realist compendium of Lebanon’s broken social infrastructure.

While the film has its flaws, it is reaches dizzying heights when the charismatic 12-year-old non-professional actor Zain Al Rafeea and the adorable one-year old Boluwatife Treasure Bankole are on screen. Zain is put through the ringer. Labaki also asks a lot of Bankole, a little girl who plays a baby boy. You can’t imagine a better double act, but you wouldn’t wish it on any child. Labaki does not want us to sit, back, relax and enjoy. She wants you to share her righteous anger.

While the film has its flaws, it is reaches dizzying heights when the charismatic 12-year-old non-professional actor Zain Al Rafeea and the adorable one-year old Boluwatife Treasure Bankole are on screen. Zain is put through the ringer. Labaki also asks a lot of Bankole, a little girl who plays a baby boy. You can’t imagine a better double act, but you wouldn’t wish it on any child. Labaki does not want us to sit, back, relax and enjoy. She wants you to share her righteous anger.

What’s with the title? Though the word is never mentioned in the film, Capernaum was the biblical town where Christ performed miracles on the downtrodden, and has come to mean chaos or ‘a place with a disorderly accumulation of objects.’ According to Labaki, her copious research into child trafficking, child labour, child abuse (depriving children of education, under-age marriages, malnutrition etc) and the plight of undocumented aliens had left her with an unwieldy list of social issues to tackle. The word Capernaum came to mind. That she tackles the list so well is a feat, but dramatically, this chaos of social issues can at times overwhelm the story.

Zain, with a thick mane of beautiful black hair, a button nose and huge, round, sad eyes looks younger than his years, but acts much older. He thinks he is 12, but his parents have too many children (they all sleep in the same filthy bed) to remember such things as birthdays. Hard-working, street-smart, intelligent, resourceful and compassionate, Zain is the kind of boy who would go far in any society with more equal opportunities. Here he works as a street hawker and delivery boy (Zain’s real life job) and participates in the family’s illicit business of selling drug-laced clothing to prisoners, through a jailed sibling. He swears profusely, but cannot spell any words.

The remarkable cinematographer Christopher Aoun, working in cramped spaces, frequently provides a wide shot or aerial view of the teaming, merciless streets that are home. Work is all Zain has known, although his mother, Souad (Kawsar Al Haddad) tells her husband (Fadi Yousef) that they should consider sending Zain to school because literate children can bring home more money.

No wonder in one of several court room scenes that punctuate the film, Zain tells the judge that he wants to sue his parents for bringing him into the world and neglecting him. After watching what Zain has gone through in the flashback scenes, the kindly judge (Elias Khoury, an actual retired judge) must realise the boy has a strong case.

Zain must also be thinking of his 11-year old sister, Sahar (Haita ‘Cedra’ Izzam), who was sold to the family’s landlord Assaad (Nour El Husseini). Her howls of protests still ring in his ears. After failing to protect Sahar, Zain runs away, returning home only to search for his ID papers so that he can pay a trafficker to travel to Norway – a country recommended to him by a street girl he meets during his Dickensian adventures. It is then that he learns the fate of Sahar. When the judge asks Zain if he knows why he is in prison, he replies: ‘I stabbed a son-of-a-bitch’.

For over half the film Zain is a runaway. Travelling by bus he descends at a sad, scruffy amusement park following a chat with a surreal beaked-nosed, spindly man in a superhero costume. The park is surrounded by a shanty town where Rahil, (Yordanos Shiferaw) an Ethiopian cleaner at the park, lives in a one room tin hovel with her baby son, Yonas (Bankole). Like Zain, who is a Syrian refugee living in Lebanon without papers, Rahil lives in fear of deportation. We have seen her at the beginning of the film in a deportation centre, not knowing why we are watching her, but we recognise the pretty young woman when we see her at the park.

When Rahil sees that Zain is homeless, starving and alone, she invites him to her modest home and before long, he is part of the family. While Rahil works, Zain takes care of Yonas, but he is still in survival mode, going nowhere with his life. It is during this long, intense, and impossibly moving, but never sentimental, interlude that the film soars to the realm of the sublime. When Rahil does not return, Zain is bemused. Can she have abandoned them? Is she no better than his own parents? He becomes Yonas’ carer, doing everything possible to keep the toddler alive. Yonas is a smart kid, but will he resist handing Yonas over to market-stall owner Aspro (Alaa Chouchnieh) for ‘adoption’, in exchange for a ticket to Norway?

This is the kind of box ticking (every misery has its moment) that, while well integrated into the story, is at times overbearing. And given the strong premise of a boy suing his parents for his rotten life, you expect this to become dramatic thread in the film. But other than witnessing the reasons for this suit, it is an unexploited premise. In the film Zain’s smart move was to use the media to make his plight known and aid workers, lawyers and police alike take notice. Watching Zain falling asleep and yawning from boredom at the Cannes Film Festival, is another side of the media. The jumping around in time with the court scenes is jarring, although it does hold out hope of a bright ending. And the rapidity with which this ending is delivered and all the ends quickly tied up is in sharp contrast to the rest of the film.

Labaki is making a kind of ‘the making of’ documentary, including the fate of the actors. In addition to the in-situ filming with hand-held cameras what lends the film its authenticity, is the intermingling of truth with ‘fiction’. That Labaki had a child herself during the production period brought out her maternal instincts. Zain’s life was similar to that of the character he portrayed, except that he is from a loving family and the entire family now reside in – Norway. Bankole and her family are settled in Kenya where they do not face discrimination. Shiferaw was in fact arrested during principal photography and the talented casting director took her daughter, little Yonas, home with her until Shiferaw was freed with the Labaki’s intervention.

Kudos to Khaled Mouzanar, Labaki’s husband and the film’s co-producer and composer. That he was able to compose such a beautiful, subtle and complementary score while serving as the first time producer of such a challenging film is another remarkable feat from this talent-house couple. Kudos, too, to Lebanon for putting forward this very critical film as its Academy Award entry.

You can watch the film trailer here: