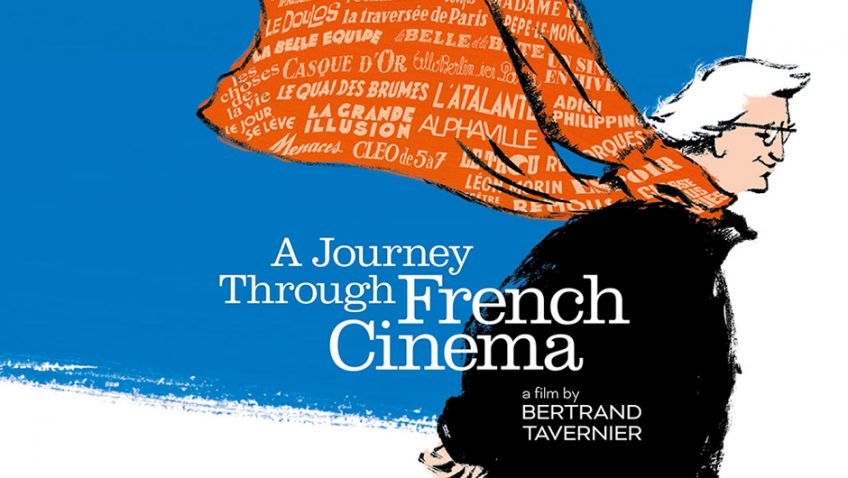

Joyce Glasser reviews A Journey through French Cinema (September 15, 2017) (Cert. 12A) 201 min

Born in Lyon, France in 1941, the engaging scriptwriter/director Bertrand Tavernier tells us that to be a child of the liberation was to be a child of the war. After WWII the sanatorium where he was treated for TB showed Sunday films. When the cinema screen lit up he was always reminded of the flares lighting the sky in September, 1944 and the joy and applause that marked Lyon’s liberation. A Journey through French Cinema is Tavernier’s entertaining love letter to the films, directors (Jacques Becker, Touchez pas au Grisbi and Claude Sautet, César et Rosalie), actors (Jean Gabin), composers (Maurice Jaubert and Joseph Kosma) that influenced his career and shaped his life. This is a very personal selection, and you probably have never heard of half of the films – but don’t let that put you off. On the contrary.

Not everyone who has started a film magazine (L’Ami du Film); a film club (Nickel Odeon); a festival (Lumière) for the preservation of classic cinema and grew up in Henri Langlois’s famous Cinémathèque Française can get away with reminiscing about their favourite movies for three hours. But Tavernier has the right credentials. He was Jean-Pierre Melville’s intern; worked as Jean-Luc Godard’s PR man; had Claude Sautet critique his rough cuts; and, after both Melville and Sautet persuaded his parents to let him make films, wrote and directed his own award winning films, such as The Bait; Life and Nothing But; Round Midnight, A Sunday in the Country, The Clockmaker and Coup de Torchon.

The irresistible film clips will leave you longing to see the entire feature while his occasionally controversial (as with Jean Renoir) anecdotes are fascinating. What makes the film so addictive is looking at films anew through his writer/director’s eyes and ears and being shown aspects of a film you might never have noticed. Talking about film scores, for instance, he says, ‘Early on I was struck by the way certain French directors used music in an original way, focusing on one or a few musical instruments rather than on the full orchestra so dear to Hollywood.’ He then gives his favourite examples while the clips provide the music he describes: ‘the guitar in [René Clément’s] Jeux Interdits (Forbidden Games); the harmonica in [Becker’s] ‘Grisbi’ (‘Hands off the Loot); the trumpet of Miles Davis in [Louis Malle’s] Ascenseur pour l’échafaud (Lift to the Scaffold).’

Bold statements, like his argument that French composers were the best in the world from the 1930s to the mid-1950s are not nationalistic when you consider his veneration of American cinema. There were reasons for this. The first is that most Hollywood directors had no say in the musical score until the mid-50’s whereas French directors worked in harmony with the composers of their choice.

Tavernier has a gift for making a director, actor or composer come alive with just a few words, like Matisse’s genius for creating a face from four lines. His portrait of the Hungarian-French composer Joseph Kosma is one of the most touching. During the German occupation of France Kosma, a Jew and a Communist, was placed under house arrest and was banned from composing. With the help of the poet and script writer Jacques Prévert, he contributed music for films with other composers fronting for him. Prévert arranged for Kosma to write the music for Jean-Louis Barrault’s famous pantomime scenes in Marcel Carné’s masterpiece, Les Enfants du Paradis (1945). Kosma wrote the scores to some of Jean Renoir’s greatest films: The Grand Illusion, The Human Beast, and The Rules of the Game and Marcel Carné’s The Gates of the Night.

Tavernier taste is nothing if not eclectic. You’ll want to see the ‘B’ movies starring American born actor and singer Eddie Constantine; particularly Jean Sacha’s 1953 This Man is Dangerous. Tavernier says he never missed one of his films.

You have to wait a couple of hours to get to François Truffaut. Tavernier was on the set of Truffaut’s first (1959 Palme D’Or winning) film, The 400 Blows, and enjoyed his second film, Shoot the Piano Player (1960) noting: ‘It was the only film I saw booed on the Champs Elysees, along with The Night of the Hunter.’

The anecdotes about the people he met (in particular Bernard Martinand) and the films he saw at the La Cinémathèque Française are interesting, particularly as they lead to two nitrate (flammable) prints of Edmond Gréville’s films, Pour une Nuit D’Amour and Le Diable Souffle, saved by the Nickel Odeon group. By the end of this section you will be longing to see all of Gréville’s films, including Remous, which examined the sensitive subject of sexual impotence – back in 1934. Gréville died prematurely in 1966 before finishing his memoirs and Tavernier and his friends from Nickel Odeon chipped in for his funeral. When the news got out they received a letter from René Clair (I Married a Witch, Bastille Day) who spoke highly of Gréville reminding the young men that he had directed Gréville in ‘Under the Roofs of Paris’. Enclosed with the letter was a cheque to reimburse them for the funeral expenses. Then Tavernier adds simply, ‘Years later, I was finally able to publish his memoirs.’

If the most laudatory segment is on the great Claude Sautet, the most entertaining segment is on Jean-Pierre Melville who gave the young critic his first job. ‘It was a thrilling experience,’ he relates, ‘but also a nightmare.’ Apparently Melville humiliated crew members on the set and fell out with actors, speaking to Leno Ventura, the star of his great resistance film Army of Shadows, through a third party assistant. In describing how he fell out with Jean Paul Belmondo, Tavernier let us hear screaming match from a clandestine recording! ‘It’s a miracle the films didn’t suffer for a second. On the contrary.’ Though Tavernier is full of admiration for Melville, two of his films come in for some serious criticism, too.

Melville appointed himself Tavernier’s mentor, and after arriving at his studio ‘3 or 4 hours late’, he would make up for it by taking the young intern out in his American car, ‘raising and lowering the electronic windows.’ After a movie or two and dinner they would drive up to Montmartre or Pigale like ‘the cops in [Melville’s] film Le Doulos, showing me the high spots of crime and the Resistance. He was a great story teller.’

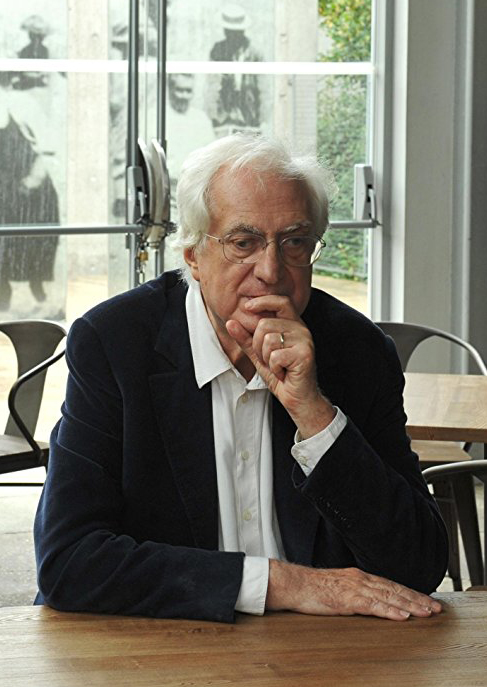

And so, you will have to conclude, is Bertrand Tavernier.

You can watch the film trailer here: