The Artist’s Wife (from April 30, on digital flatforms). Cert TBC, 96 mins.

It is a terrible irony that, dementia, the cruellest disease inflicted on older people, has spawned a sub-genre in cinema and given many older actors weighty, central performances that would otherwise not be available. As long as the scripts keep coming, most older actors want to keep on working. And this presents another irony, as these actors who are still able to remember their lines and get up at dawn and put in a full day of intense concentration, must convince us they are incapable of doing any of that.

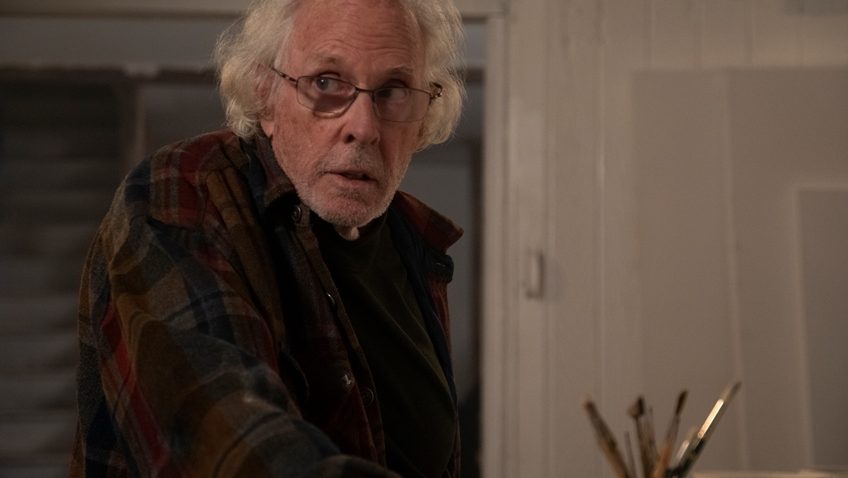

If 83-year-old Anthony Hopkins’ Oscar winning performance in The Father is the gold standard, 84-year-old Bruce Dern does an impressive job convincing us that he is Richard Smythson. Smythson is a wealthy, egocentric artist and celebrity art teacher whose perfect life is about to be railroaded by worrying signs of Alzheimer’s. And Dern, who was Oscar nominated for his role as a father beset with Dementia in Alexander Payne’s film, Nebraska, has had practice.

Smythson shares a flashy, architect-designed house in the Hamptons with his devoted, attractive second wife, Claire (Lena Olin, The Reader, The Unbearable Lightness of Being), who is, though twenty years younger, solidly middle-aged. Although the two have no children, Smythson has an estranged daughter, Angela (Juliet Rylance – Mark Rylance’s daughter) from his first wife, and Angela has a grandson whom Richard has never met.

Claire gave up her own painting career when she married this irresistibly talented and charismatic man and for twenty years, she has been the woman behind the famous man. Now, she appears to show her love in another seemingly altruistic way, when she decides to engineer a reconciliation between Richard, and his estranged family while there is still time for them to get to benefit one another.

It seems like a cliché that when Claire travels to New York City on her mission, she becomes involved in another dysfunctional family saga, as Angela has just been dumped by her lesbian partner and is distraught. Angela is financially independent, but she is fragile and the last thing she is ready to do is forgive the father who was never there for her.

This subplot might seem like a hackneyed distraction, but it ties in with the story’s true focus, which, as the title suggests, is the eponymous Claire. Perhaps Claire is hoping that Richard’s involvement with his “new” family will take the pressure off her and facilitate her bid for independence.

For although Alzheimer’s brings out the worst in this already difficult man, Claire finds it liberating that she no longer has to support his career. Caring for a man who expects nothing and of whom nothing more is expected, is infinitely easier than bearing the burden of managing the busy, pressured life of a demanding, famous artist. This epiphany leads Claire to resume her own painting in a hired studio.

A short-lived fling in her studio with Claire’s handsome, male nanny Danny (Avan Jogia) not only boosts her confidence (Olin has kept her gorgeous figure) but cements this newfound independence.

Director Tom Dolby, who co-wrote the script with Nicole Brending and Abdi Nazemian, was partly inspired by his famous father, Ray Dolby of Dolby Sound, who suffered from this indiscriminate infliction. Dolby’s film is interested in how the disease affects not just the sufferer, but the family. And Alzheimer’s has also created meaty roles for actors portraying the children and spouses of its victims.

With inspired casting, the magnificent Olin, absent for too long from our screens, is the real reason to see this film. It is through Claire that Dolby begins to introduce this notion that Alzheimer’s can, on both a psychological and physical level, liberate the woman-behind-the-man. It is just a shame that he does not delve deeper. Olin’s physical, spontaneous and instinctive performance props up the script so well that we hardly notice.

There are a lot of big, abstract canvases in The Artist’s Wife, both Richard’s and, increasingly, Claire’s, as it starts to dawn on us that there is a parallel here with Tim Burton’s biopic Big Eyes. The art is disappointing, which is almost always the case in fictitious artist films, but we can ignore that. What is more difficult to ignore is the haste with which Claire’s final sacrifice unfolds, depriving us of a satisfying final act.