Joyce Glasser reviews A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence (April 14, 2015)

If you have not seen the first two films in this trilogy by Swedish filmmaker Roy Andersson, Songs from the Second Floor and You, the Living, then the title of the third film should warn you that are not going to see a conventional or mainstream film.

Despite the title, the trilogy, Andersson tells us, ‘is about being human.’

If you think the films of fellow-Swedish auteurs Aki Kaurismaki (Le Havre) or Bent Hamer (O’Horten) are quirky and meticulously paced, you haven’t seen anything yet. The film was awarded the Golden Lion for Best Film at the last Venice International Film Festival, but it is not your typical crowd-pleaser.

Although A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence is indeed cryptic, and you might spend the duration of the film scratching your head, the meaning is probably revealed fairly starkly in the first scene.

An unhealthy looking sixty-something man with white hair and a white face stands in front of a glass display case in a natural history museum as his impatient wife looks on, almost out of the frame.

The focus of the man’s attention is an ordinary stuffed pigeon sitting on a branch. The man is contemplating the existence of the pigeon in the case; while the pigeon is looking out at the man; and we are watching the man through the cinema screen.

In the following scene the man is back at home where his wife, again in the background, is preparing a meal. While attempting to open a bottle of wine the man drops dead.

Though the unassuming stuffed pigeon might seem meaningless, it is one of many of the film’s characters, objects and events with cultural connotations that intertwine our cultural heritage and history with the absurdity and pathos of everyday life.

Housed in the Bruegel Room in the Kunsthistorisches Museum (Museum of Art History) in Vienna, a bird resembling a pigeon appears in the painting The Hunters in the Snow by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Through the frozen, grey landscape two hunters and their dogs return to their village, bent over, exhausted, and with little in the way of bounty to show for it.

Several birds are perched high on the thin branches of barren trees, observing the scene below as though attempting to make sense of it.

There is no real plot to this episodic film, but there are two anti-heroes in the form of a pair of travelling salesman. And it is not long before their relationship and the great sadness of their existence reminds us of Vladimir and Estragon in Waiting in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

Jonathan (Holgar Andersson) and Sam (Nils Wesblom) are not just any salesmen, but two particularly doomed salesmen, specialising in novelty joke paraphernalia. With their beleaguered manner, deadpan expressions and laborious sales pitch, they are clearly the wrong people for the job. Then again, it is hard to imagine anyone else who would take it on.

Jonathan (Holgar Andersson) and Sam (Nils Wesblom) are not just any salesmen, but two particularly doomed salesmen, specialising in novelty joke paraphernalia. With their beleaguered manner, deadpan expressions and laborious sales pitch, they are clearly the wrong people for the job. Then again, it is hard to imagine anyone else who would take it on.

They hang around in hotels and waiting rooms for appointments with people who either do not want the pathetic toys or who have purchased them on bad credit and cannot pay for them.

The men are under pressure from their boss who they keep at bay with the help of the concierge at their rooming house.

On their rounds Jonathan and Sam weave in and out of various locations that form the film’s unpredictable medley of set pieces. One of the most astonishing is Lotta’s Bar, a WWII bar/restaurant that yields a big musical number as the male clientele, soldiers and veterans, pay tribute to the disabled Lotta to the tune of ‘The Truth is Marching On.’

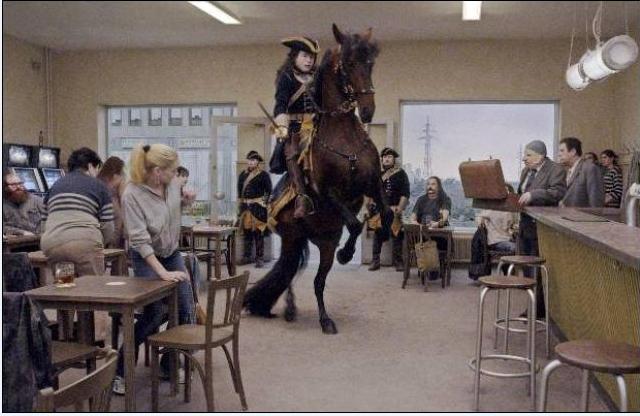

Adding to the epic nature of the film in its sweep of history is a shocking scene involving slaves and their masters. There is also an impressive set piece in which the two salesmen stop in a contemporary bar that is gradually engulfed in the 18th century wars of Sweden’s young, homosexual King Charles XII.

The salesmen watch silently as an imposing rider on a stunning stallion enters the bar preparing the way for the triumphant King who is immediately attracted to a good-looking male waiter. The pomp and circumstance is far more modest when the King’s defeated army returns in tatters from his disastrous march on Russia in 1718.

The salesmen watch silently as an imposing rider on a stunning stallion enters the bar preparing the way for the triumphant King who is immediately attracted to a good-looking male waiter. The pomp and circumstance is far more modest when the King’s defeated army returns in tatters from his disastrous march on Russia in 1718.

August Strindberg wrote a play about him, Voltaire saluted him, and Samuel Johnson wrote a poem about him. The statue in Stockholm with King Charles’ arm stretched out toward Russia, is seldom without a pigeon perched on the celibate, childless monarch.

Since we never know what to expect, the sheer novelty of the exquisitely staged and infinitely varied chapters keep us watching. At times we do not know whether to laugh or cry, like the sad clowns who peddle jokes in a humourless world.

The problem with a seemingly random series of vignettes, a static camera and uncommunicative characters (many wearing white grease paint), however, is that there is no tension, character arc or plot development to involve us.

As a result the film is less compelling and likeable than worthy of admiration for the incredible creativity and intellect behind every frame.

You can see a trailer of the film here: