Joyce Glasser reviews 1917 (January 10, 2020), Cert. 15, 119 min.

Although this WWI film missed the run of films and tributes that appeared from 2014-2018, we are lucky to have it at all: a $90 million war movie, starring two relatively unknown actors and one unknown actress in a cameo. But when the director is Sam Mendes, who co-wrote the script with Krysty Wilson-Cairns, based on stories his veteran grandfather told him, the proposition seems less risky. And when the film is shot and structured to make you feel that you are on a white-knuckle ride, the audience appeal is widened.

A caption tells us it is April 6th, 1917. Leaning against a tree asleep during a brief break, Lance Corporal William Schofield (George MacKay) and his mate, Lance Corporal Tom Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) reposing nearby, are disturbed when instructed to report to General Erinmore (Colin Firth, in a cameo).

You know that you are in for a breathless, epic adventure when you are plunged into the trench, racing to keep up with the two men, as they wind their way through the mud and scores of bored, tired, frightened soldiers. To Blake, who is hungry, Schofield says, ‘this time next week, you’ll be eating chicken dinner,’ only to learn that Blake’s leave has been suddenly cancelled with no reason given. Schofield is ambivalent about leave, as he knows that while it is difficult to return home after the horrors of trench warfare, it is even more painful to leave again to return to the front.

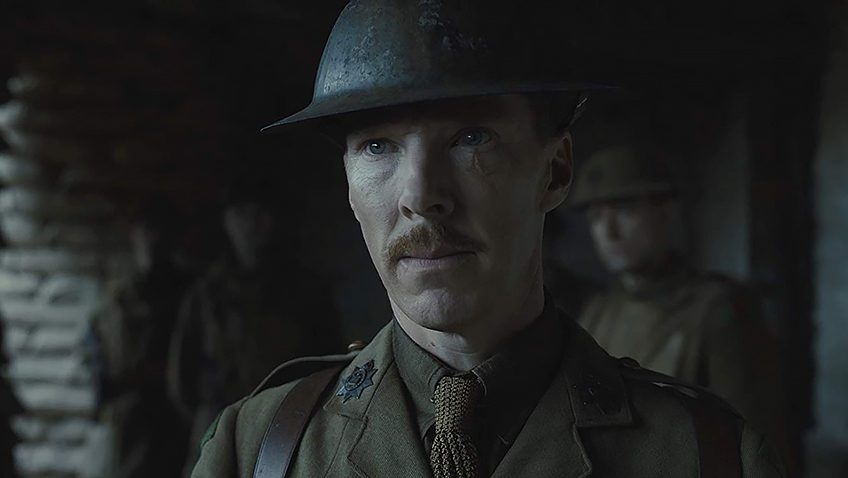

The young men are bemused at this summons to the high command and General Erinmore, does not beat about the bush. The Germans have abandoned their position across no-man’s land in what is first thought to be a retreat, and the Second Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment, led by Colonel Mackenzie (Benedict Cumberbatch in a cameo) is planning a surprise attack on the retreating army at dawn. Erinmore, standing before recently delivered documents, briefs the two young men that aerial footage reveals this to be a trap. The German move is a tactical withdrawal to their new (Hindenburg) Line.

Benedict Cumberbatch in 1917

As the field telephone lines have been cut, Erinmore needs the two young men to hand-deliver to Mackenzie his written orders to call off the attack before 160,000 soldiers are slaughtered. Before they leave the camp, they are to be further briefed on the best route by Major Stevenson in the front line of the Yorks.

You might wonder why Erinmore entrusts such a vital message and a tactical journey to two ordinary soldiers who are usually frontline fodder. Presumably, motivation trumps experience and track record, for Erinmore mentions that Lieutenant Joseph Blake (Richard Madden), Blake’s older brother, is in the Devons and may well be leading the charge.

When the duo reaches Major Stevenson, they are told he has been killed in a skirmish so recent that the wounded have not been collected and bodies and horses lay rotting in the mud. A cynical, weary Major Leslie (Andrew Scott, wonderful in this cameo), surprised to hear of the retreat, gives the young men what tips and instructions he can to get them across no-man’s land.

George MacKay and Dean-Charles Chapman in 1917

Schofield is cautious, suggesting that they wait for nightfall. When Blake pushes on for his brother’s sake and Schofield jokingly accuses Blake of chasing a medal, Blake retorts that Schofield did well out of the Somme. Schofield confesses that he exchanged his Thiepval medal for a bottle of wine. ‘It’s just a piece of tin’, he says, and at this point, if you have seen a sufficient number of coming-of-age or war movies, you will realise that the film’s real journey will be Schofield’s. Whether Mackay has the charisma and talent to carry a film like this is not what we dwell on.

Mendes won an Academy Award for his first feature, American Beauty, and directed Skyfall, arguably, the most successful James Bond to date. He popped back to the West End to direct the superb, The Ferryman, before collecting a Tony Award for Best Director last year when it transferred to Broadway. Although Mendes is one of the few stage directors whose transition to film has been a resounding success, you would not expect him to prioritise form and technique over content as he does here, attempting an immersive, and, in Mendes’ words, ‘real-time’, experience by going for the continual take technique used so brilliantly in Hitchcock’s Rope, Sebastian Schipper’s thrilling Victoria and the Academy Award winning Birdman.

John Hollingworth in 1917

But 1917 was shot in Scotland and across various locations in England over 65 days, so a lot of edits are cleverly covered up to sustain the idea of a single take. And when Schofield is knocked unconscious by a German sniper, the screen fades to black, clearly abandoning the continuous take. Though Roger Deakins’ superb cinematography produces the desired visceral effect that put us in the line of fire, it can also be emotionally alienating and produce some odd results.

The idea of real-time is never achieved, as the journey, which seems to go from day to night to dawn, is far longer than the film’s running time. And how possible is it that in the silence of a farmhouse on a hill, the two Lance Corporals would not see or hear the approach of Captain Smith’s (a superb characterisation squeezed into Mark Strong’s cameo) regiment – revealed to us as we emerge from the farm by a tracking shot? Smith offers to give Schofield a ride to Écoust-Saint-Mein, the town nearest to Mackenzie, but when he is dropped off to cross the destroyed bridge over a narrow canal that separates the convoy from the town, he is wounded by a German sniper. Why, given the importance of the mission, does Smith’s regiment not remain long enough to cover Schofield as he crosses the canal?

Colin Firth in 1917

If you have seen a sufficient number of films modelled after video games, like The Hunger Games or the Jumanji franchise, Erinmore’s instructions sound like those given to the players by the game’s guide reciting the rules of the game. Once the rules are clear to the two Lance Corporals and the audience, the nonstop action, and the suspense of ‘will he make it?’ begins. The film is reduced to this question.

In contrast to WWI itself, which was a curiously stagnant war, in which troops fought for months over a few metres of land, the forward propulsion here cannot be stopped, and the obstacles are varied and unexpected. When Schofield dodges a sniper attack by running through the ruins of the town and jumping into conveniently awaiting rapids below, we are immersed – but in a familiar, video game-inspired film.

You can watch the film trailer here: