Gianfranco Rosi’s documentary, ironically entitled Sacro Gra (Holy Grail), is a road movie of a different sort, depicting life along a varied, though primarily modernised ring-road highway that surrounds the ancient city of Rome.

Among the brown-field waste-lands, soulless high-rises, factories and dumps, there is an aristocratic manor house for hire, touching family lives, snow-covered sheep grazed fields, and a botanist fighting a crusade, Don Quixote style, to rid the palm trees of an insect epidemic. The film, which required two-years of filming, was inspired by Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. That novel is essentially a series of prose poems in which Marco Polo describes his travels to the Empire-building Emperor Kublai Khan.

What is striking about Rosi’s documentary is that there is no narration or attempt at explaining the frequently bizarre and random slices of life he presents as his ‘visual poems,’ in response to Calvino’s. Take the botanist mentioned above who combines his field work along the ring road with research in his tiny, cluttered, but well-equipped laboratory.

‘It’s the sound of an orgy,’ he relates listening through magnified ear phones, regretting that ‘we aren’t organised to fight such an invasion.‘ Although the evidence is ‘devastating’, he squeezing a beetle in his fingers, vowing, ‘this is the prelude to my revenge.’ There is no context given for his ambitious endeavour.

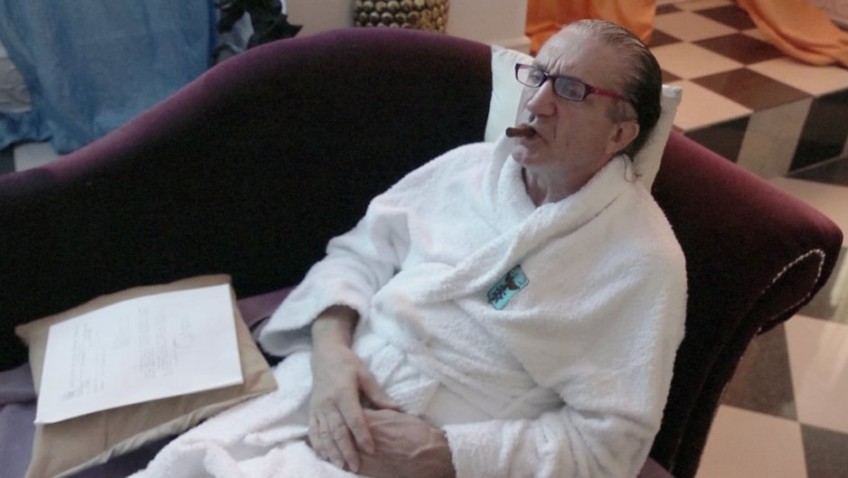

Then there is a cigar-smoking aristocrat whose inherited castle looks like something out of a Cinecittà film set, at least from the inside. But this is no wealthy prince charming, and he is forced to hire it out. It serves as a Bed & Breakfast, film set and a ceremonial hall. It seems a Lithuanian diplomat has hired it and the proprietor shows up in full costume party attire.

A lonely, middle-aged ambulance worker untangles drivers from their vehicles and tends to mistaken heart attack victims with a sense of humour before returning home to tend for his dementia-afflicted mother.

Two prostitutes of a certain age share a cigarette, small talk and a bite to eat in their ramshackle caravan while, in a high rise flat, a father talks incessantly to his daughter who is busy searching the internet for a husband. Rosi shoots his high rise stories from outside the building and we peak down at an awkward angle into the flats so that we never clearly see the faces of the inhabitants.

In another segment, two women admire the beautiful panoramic views (which we never see), but lament the change in the area which has hemmed in charming, independent villas way down below.

The most touching, lyrical and self-contained segment introduces us to one of the last of a long-line of eel fishermen who are out at dawn and dusk on the Tiber river. He reads the paper and rants about pollution while his silent wife, who has heard it all before, mends the nets.

‘You keep on cutting and sewing,’ he teases her. ‘They call you Penelope,’ referring to Ulysses long-suffering, but faithful wife’s ruse for not remarrying, while awaiting her sea-faring husband’s return. He proposes ‘moving on,’ but we get the impression he can no more leave the river than his grand-father before him.

Not all of the segments are this enjoyable and the film, which in some cases denies us audible dialogue, requires patience with a few longeurs. Rosi is, however, true to his source material in delivering a film that, like Calvino’s novel, presents an alternative approach to looking at the way cities function.

Joyce Glasser – MT film reviewer