Joyce Glasser reviews Paris Calligrammes (August 27, 2021, in selected cinemas) Cert. 15, 129 mins.

In his novel Requiem for a Nun, the American writer William Faulkner wrote, “The past is never dead. It is not even past.” In writer-director-cinematographer Ulrike Ottinger’s remarkable, immersive documentary, the German artist revisits a thrilling decade of her past and, magically resurrects it through a prism of 50 years using the medium of a film montage.

If this journey were only vicarious nostalgia, it would be well worth taking because Ottinger’s experiences are so seeped in history that she is a vital eyewitness. But Paris Calligrammes becomes even more rewarding and rejuvenating because the 79-year-old returns to her Parisian haunts finally able to capture and crystalise what it was that made the period so exciting, diverse, transformative, and for all its follies and dark side, so enlightening.

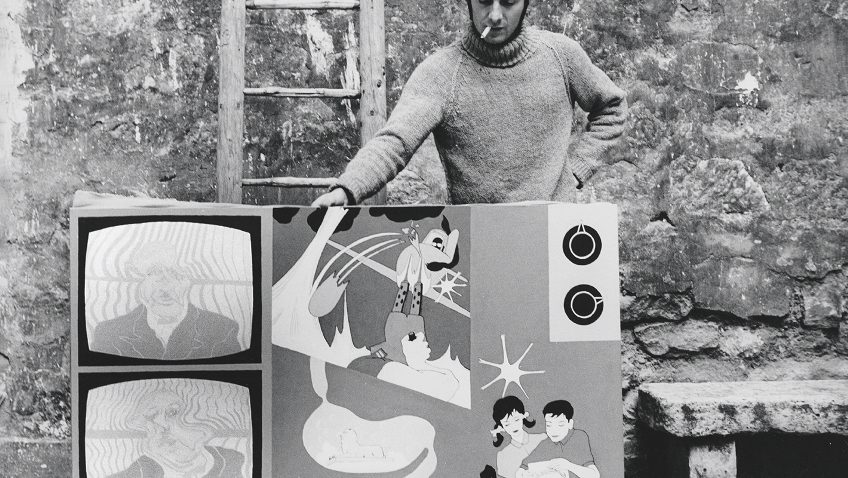

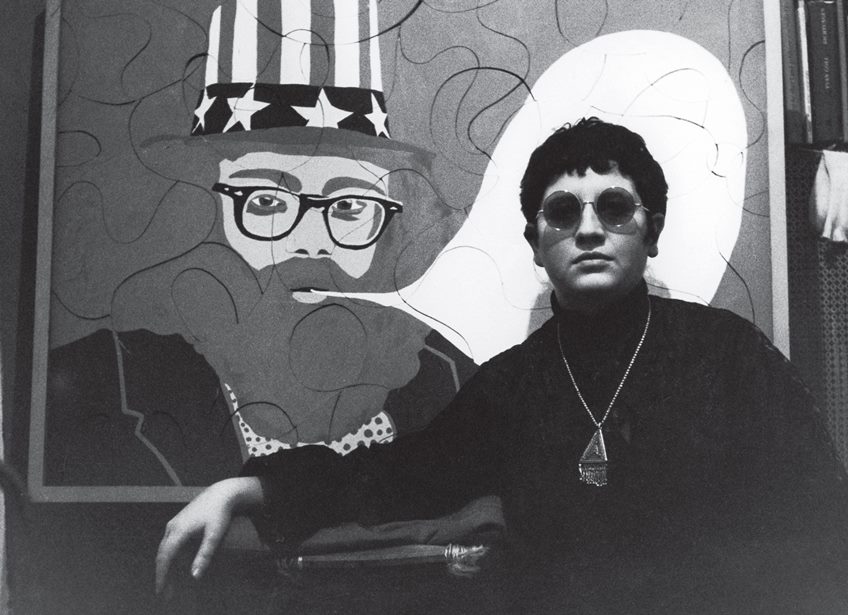

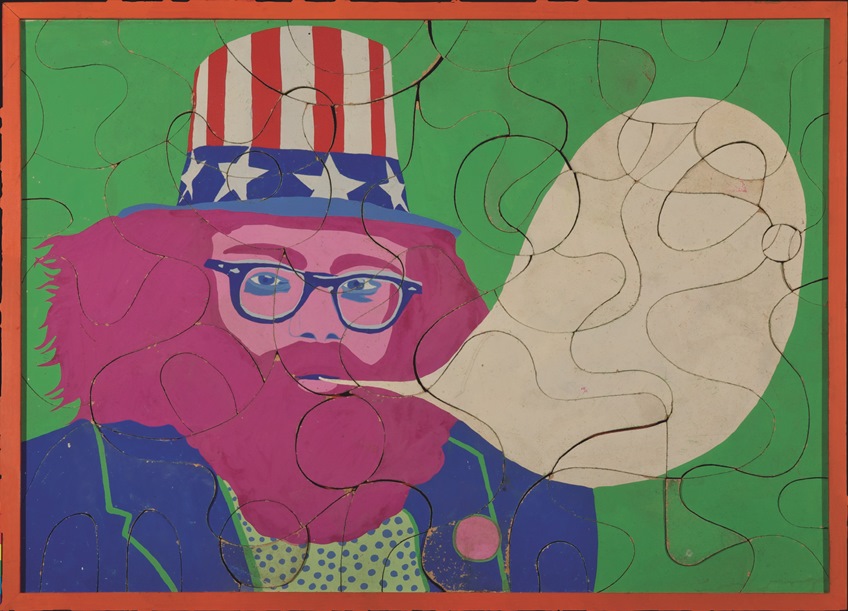

Mixing her art and excerpts from her surreal-styled films with those of her “heroes”, along with rare, archival footage, new footage, not to mention Fritz Picard’s guest book, signed by everyone from Marcel Marceau to Paul Celan, Ottinger revisits the Paris of the 1960s, from her arrival as a wide-eyed, elated 20-year-old to her disillusioned departure after the 1968 riots.

There are probably many British people who, like Ottinger, hitchhiked across France to Paris in their youth to become part of the last artistic flowering of the capital. The 1960s followed the Belle Epoque (1880-1914) and the roaring Twenties, when a wave of new ex-pats like Hemmingway, F Scott Fitzgerald and Josephine Baker highlighted the jazz culture and the innovative artistic (surrealism) scene.

In the 1960s you could still see Simone Signoret at a café on the Boulevard St Germain reading a script and you could still wander through France’s central produce market, Les Halles, at dawn after a night out at a jazz café hearing Barbara sing Quand Reviendras Tu. You could spend entire rainy days at Henri Langlois Cinémathèque Française watching French New Wave films that revitalised the staid French cinema from Truffaut’s The 400 Blows in 1959 through the early 1970s.

You could still attend the lectures of “the father of modern anthropology”, Claude Levy-Strauss at the College de France, whose writing contributed to Ottinger’s filmmaking. As he wrote, “to know and understand your own culture you must learn to view it from the perspective of another”. Sartre and De Beauvoir were not only still spotted in town but, when during the 1968 riots and strikes someone suggested to De Gaulle that Sartre be arrested, he replied, “You don’t arrest Voltaire”. And you can still, today see the exterior of Dadaist Tristan Tzara’s house in Montmartre, built in 1925 from designs by the great Austrian architect Adolf Loos.

Many of us, too, might have visited the then Musée de L’Histoire de L’Immigration, but here’s where our nostalgia fades into Ottinger’s ever-sharp mind, as she returns to Paris 50 years older to put it all in perspective. There is no better example of this perspective than this museum, grand and imposing, if off the beaten track at the Porte Dorée. While Ottinger marvels at the monumental sculptures of the 1930s, she is freshly troubled that they depict the people from France’s colonies offering cotton, silk, spices, copper, fruit, zinc and other “sacrifices” to the ruler. As Ottinger narrates, “The mere act of renaming the Museum of the Colonies to the Museum of the Art of African and Oceania, and most recently, to the Museum of the History of Immigration is a testament to social and political upheaval”.

And Ottinger’s segments on political upheaval, notably France’s Algerian problem, is as riveting as are her segments on art and culture. She focuses her discussion on Jacques Panijel’s 1962 film October in Paris that was the hot topic when Ottinger arrived in the city. Through re-enactments and documentary footage, Panijel documents the impossible conditions in which Algerians lived (in shanty towns on the outskirts of Paris) and the 1961 riots that broke out when a peaceful demonstration organised by the FLN, the Algerian Liberation Movement, was brutally attacked by the racist Police Chief Maurice Papon. Cinephiles will recognise Papon from Mathieu Kassovitz’s acclaimed and influential 1995 film, La Haine (Hate), recently re-released here. Ottinger adds that Papon was an enthusiastic Nazi collaborator in WWII.

The film begins, however, with a part of Paris few of us will remember. Despite the political tensions between the Germans and French after WWII, French artists and literati mingled with German émigrés at Fritz Picard’s bookshop, Calligrammes. Picard was a mentor of the young Ottinger, and her footage and recollections of the bookstore, and nights in his welcoming apartment, will make all book lovers nostalgic for such meeting places. She dares to devote nearly five minutes of screen time on a recording (documented with photos and illustrations from his books) of Walter Mehring reciting his shattering, WWII eulogy, In Memoriam… At the time, tears filled the eyes of those fortunate enough to hear Mehring, but the recital here loses little of its emotional power. More boisterous but equally thrilling is her recollection of the bagging of a hot ticket for Jean Genet’s taboo busting Les Paravents at the Théâtre de L’Odéon in 1966 that was attacked by the right-wing (often before having seen it) for its symbolic condemnation of the Algerian War.

“I followed the footsteps of my heroines and heroes,” Ottinger narrates, “wherever I found them, they will appear in this film too”, she promises. There are the Jewish exiles like Fritz Picard, who left his library of 7,000 books behind in Berlin, only to start anew in Paris. There was Johnny Friedlaender’s studio where people of all nationalities (including Ottinger) learnt print making, with the poor students subsidised by wealthy American visitors. Another hero is the researcher-filmmaker at the Musée de l’Homme, Jean Rouch, the creator of “ethnofiction”, and the Surrealist poet, critic and political activist Philippe Soupault, who left everything behind when he escaped from a Nazi prison. Ottinger credits Soupault for “jumping into our debates [at the Brasserie Lipp] on the Algerian War with points of clarification” and “dampen[ing] our enthusiasm for the new Socialist Algeria”.

As for the title, Ottinger explains: “Like Guillaume Apollinaire’s [1916] poetry collection Calligrammes: Poems of Peace and War, I have given [my film] the form of a filmic “picture-poem” (calligram) …that emerges from…those exciting years while speaking to the fragility of all cultural and political achievements.