Joyce Glasser reviews The French Dispatch (October 10, 2021) Cert 15, 108 mins.

From the sound of it, you would have to be a bitter Brexiteer or a morose philistine not to love Wes Anderson’s new film, The French Dispatch, which has been described as a “love letter to journalists” and clearly to actors, as it boasts the starriest international cast of A-listers of the decade. Shot in Angoulême in Southwest France, it is also a personal love letter to France where Anderson lives. Above all, it is a tribute to the New Yorker Magazine a bastion of intellectual integrity and great writing across borders that is disappearing in this Amazon-driven, self-publishing, short attention-spanned, polarised, digital age.

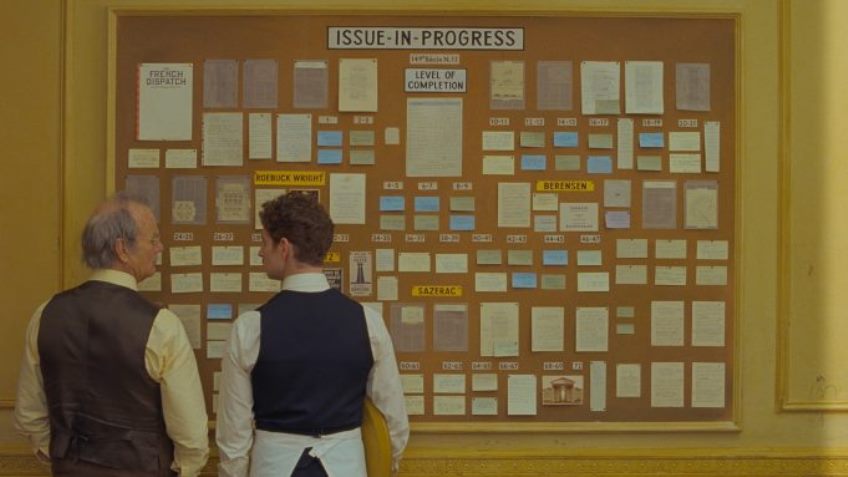

The French Dispatch, located in the colourful city of Ennui-sur-Blasé (‘boredom-on-Blasé – drôle, non?), is a foreign off-shoot of the Liberty, Kansas City Sun published by the legendary Arthur Howitzer Jr (Anderson regular Bill Murray) whose funeral signals the end of an era and the trigger for the anthology film to follow.

Howitzer mandated that upon his death the publication would cease functioning pending one final issue. What we see is that final issue, and includes an article about the funeral, and four representative articles from past issues. Howitzer is one of those rare editors who encouraged great novelists to write a short story; allowed writers to go over word limits, and who could draw out a good story from writers unaware they are sitting on one. Howitzer is based on Harold Ross, who co-founded The New Yorker in 1925 and remained editor-in-chief until his early death in 1951. The best, or sincerest scenes in the film are the conversations between Howitzer and the various writers about their commissioned articles.

On Howitzer’s death, Anjelica Houston (another Anderson regular), takes up the expository narration that is so stuffed with information and so rapidly delivered, that when montages of images start appearing you don’t know where to look, or whether to listen or look, or even whom to listen to, as there are stories within stories.

The dullest, least convincing story is The Cycling Reporter by Herbsaint Sazerac (Anderson regular Owen Wilson) providing a bird’s eye view tour over time of notable haunts, such as the Sans Blague (no kidding – drôle, non?) café. We feel no connection to these places, and whether or not they are based on real-life places is a moot point if no one knows and we never find out.

The most accessible and involving segment, The Concrete Masterpiece, is introduced by art expert J.K.L. Berensen (Tilda Swinton) during a lecture to a crowd in an anonymous hall. She tells the fable-like tale of the idiosyncratic, uncouth painter Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio del Toro) who, like the Parisian writer Jean Genet (1910-1986), creates art in prison until the glitterati of society discover his talent and turn him into a cause célèbre. Moses’ muse, model and lover is a voluptuous prison guard (Léa Seydoux) who maintains a professional detachment from the pining artist.

While this story is entertaining, more interesting is the woman who inspired the Berensen character, Rosamond Bernier, whom The New Yorker profiled in their January 19, 1987, issue. It’s worth checking out. “Rosamond Bernier has the lecturer’s equivalent of perfect pitch. Forty or fifty times a year she sails into her subject for the evening with a confidence and brio that rule out any possibility of boredom.”

The possibility of boredom is not entirely ruled out in the third segment, “Revisions to a Manifesto”, even by the pairing of the charismatic heartthrob Timothée Chalamet playing student revolutionary Zeffirelli and triple Oscar winner Frances McDormand playing New Yorker journalist Lucinda Krementz. Krementz is no doubt modelled after Mavis Gallant, a Canadian writer who moved to Paris in 1950 to write short stories. By 1968 she was writing from Paris for The New Yorker (as was the writer Janet Flanner, known as “Genet”). The French Dispatch assigns her a story about the student revolution and revolutionaries, and she takes an interest in Zeffirelli.

Zeffirelli ends up in bed with Krementz, compromising, in the words of Zeffirelli’s girlfriend Juliette (Lyna Khoudri) her “journalistic integrity.” Zeffirelli writing nude in the bathtub like blacklisted Dalton Trumbo, or more to the point, like revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat – killed by a woman who disagreed with his politics – is amusing, but these conceits make it harder to believe in Chalamet’s character. Meanwhile, we register that Anderson is again playing around with names, as the director Franco Zeffirelli directed a famous film version of Romeo and Juliette (the girlfriend’s name).

It is more rewarding to read Gallant’s The Events in May: A Paris Notebook — II that appeared in the September 13, 1968, issue of The New Yorker. Gallant did not rewrite a student leader’s manifesto, as Krementz does for Zeffirelli, but she captured the movement with journalist integrity and insight, as does filmmaker Ulrike Ottinger in her recent autobiographical documentary, Paris Calligrammes.

New Yorker editor Harold Ross was famous for his belief that copy should be clear and concise, and that writers should not assume that readers, even New Yorker readers, knew who famous people were. By the time we get to the final article, The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner, the exposition, and layers of stories within stories is so dense that you might long for some clarity. The cast for this section alone includes such great actors as Mathieu Amalric, Willem Dafoe, Saoirse Ronan, Liv Schreiber, and Edward Norton, but if you get distracted trying to follow the thread of the piece, you will miss them.

This whimsical, madcap section is framed by a television interview with Roebuck Wright (actor Jeffrey Wright), modelled after James Baldwin, one of several black people who escaped the racism and homophobia of the USA for Paris from after WWI to the 1960s. Anderson is clever, and he wants us to know it, so rest assured that in 1948, the real Baldwin, then 24, and his fellow-compatriot Richard Wright had a famous argument at the Brasserie Lipp about Baldwin’s article in Zero magazine that criticised Wright’s “protest novel”’ as sentimentalism.

The fine actors adopting Anderson’s signature style look as if they are having a blast, but can the same be said for the viewer? There is an emotional hollowness to the characters and their stories that keeps us at a distance. The cleverness, visual brilliance, and erudition in Anderson’s film is drowning in self-indulgence in this tantalising, but indigestible smorgasbord.