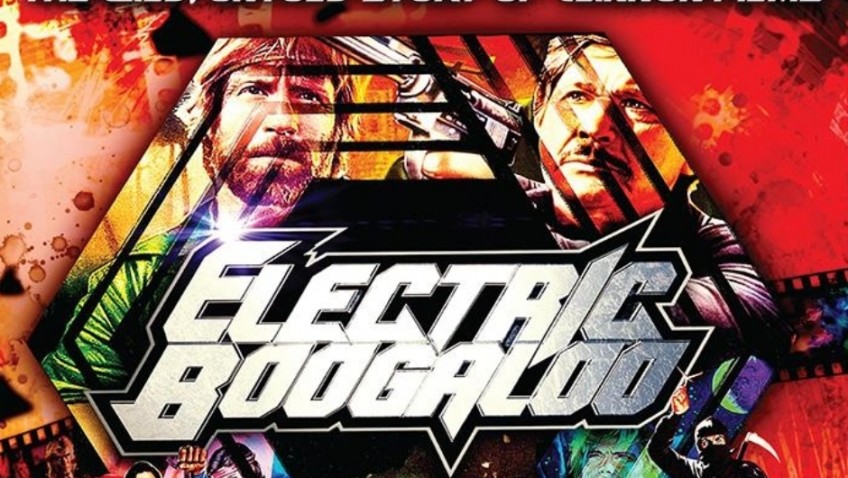

Readers who went to the movies on a regular basis in the 1980s will have seen, if only by accident, at least one film distributed by Cannon Films, a company founded in 1979 by two Israeli-born film-obsessed cousins, Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus. Electric Boogaloo is as much about the cousins, deemed ‘maybe the best film salesmen you’ve ever seen’, as it is about the films with which they are identified. While there are some laughs to be had, and some great anecdotes, given the characters of Golan and Globus, a better made film would have provided more entertainment value and insights

The films with which the cousins are identified range from their steady (too steady) stream of outrageous, overblown and exploitative films, from Bo Derek’s Bolero and the Texas Chain Saw Massacre to Death Wish 3 & 4 and Revenge of the Ninja series, to surprise gems, like Runaway Train and Zeffirelli’s Othello starring Placido Domingo.

The Producer, Director and ‘creative’ head, Menahem Globus (he changed his name to Golan in 1948) and his younger cousin, the financial wizard Yoram Globus, were not upstarts who came from nowhere to purchase a failing American studio in 1979. In Israel, they paid their dues for years, producing and distributing films for the local market, starting with El Dorado in 1963. The pair’s company, Noah Films, gained recognition overseas when their 1964 film Sallah was nominated for an Academy Award in the Foreign Language Category. They finally seized on their chance to break into the US and international market when The failing Cannon Group, Inc came up for sale.

Once the cousins hit Hollywood the tiny Cannon Group began pumping out more films than the major studios, remaining one step ahead of the creditors thanks to Globus’s shrewd business skills and talent for pre-sales to foreign markets. The cousins not only worked with high-profile stars of the 1980s including Sylvester Stallone, Sharon Stone, Sean Connery, Chuck Norris, and Faye Dunaway, but with directors like the late Michael Winner and Robert Altman, as well as Godard and Franco Zeffirelli.

Although the cousins angered as many people as they impressed, Zeffirelli sang their praises while they saved John Cassavetes. One commentator tells us that Cannon gave money to Cassavetes, “who couldn’t get money from anyone” toward the end of his short life. With the money, he made Love Streams, starring himself and his wife Gene Rowlands. The film won the prestigious Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival and the late American critic, Roger Ebert praised the film, giving it 4 out of 4 stars.

But classy, art house films like Love Streams were not the norm. One commentator said, ‘What they lacked in taste, they made up for in enthusiasm.’ The cheesier films with nudity, blood, and no pretence to moralistic messages in them, were the norm. They were occasionally directed by Menahem, who famously said, ‘If you make an American film with a beginning, a middle and an end, with a budget of less than five million dollars, you must be an idiot to lose money.’

It’s when the brothers stretched beyond their remit and comfort zone and embarked on films such as Superman IV, the first Superman film not to be produced by the Mexican father and son team, Alexander and Ilya Salkind, that Cannon’s days were numbered.

Mark Hartley, who made Not Quite Hollywood and Machete Maidens Unleashed, includes a fleeting stream of well-known talking heads, entertaining film clips and biographical facts, but demonstrates less flair in putting them all together. The style of presenting the quasi chronological history of the company and the films begins to grow tedious with Hartley’s relentless pacing. Hartley’s film is balanced, and we come away with an admiration for these two mavericks, tinged with regret at their failings. Given the subject matter, however, this could have been a better film.

That said, an anecdote related to the production of ‘King Solomon’s Mines’ which says everything about Cannon’s way of making films is worth the price of admission alone. Apparently, in 1984, after seeing Kathleen Turner in Romancing the Stone, Menahem wanted to make something similar, and came up with the idea of King Solomon’s Mines. According to the legend, he shouted to some casting person, ‘Get me that Stone woman.’ Menahem was horrified when he saw that a minion had obtained a television actress named Sharon Stone. Realising the error he shouted, ‘No, I meant the girl from Romancing the Stone.’

Joyce Glasser