Joyce Glasser reviews Vice (January 25, 2019), Cert. 15, 132 min.

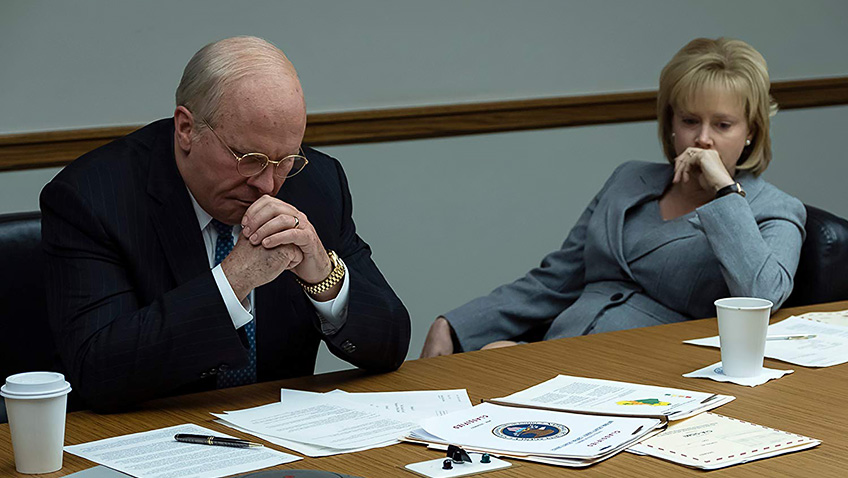

Almost exactly three years ago, Adam McKay’s fast and furious caustic send-up of the subprime mortgage lending scandal, The Big Short, gave Christian Bale another great character to play in an ensemble cast (which included Steve Carell) and he stole the show. Now McKay, whose tongue-in-cheek portrayals of anchormen (Anchorman: he Legend of Ron Burgundy), race car obsessives Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby and bungling buddy cops (The Other Guys) have established him as a major mainstream comic talent, turns to politics. But don’t worry: Vice is not a conventional biopic of Dick Cheney, but a cross between a send-up of American politics, a horror movie and an Awards vehicle for an unrecognisable Christian Bale who, with the help of prosthetics, nails Cheney’s face, neck, hair, voice, manner of walking and personality. Still, told in The Big Short’s fast-paced, glib, overbearing style, there might be more to admire than to like about Vice

.

If you can’t remember much about Dick Cheney that is probably the way he wanted it. This is a man who felt comfortable in the background, but, as VP to the impressionable, weak George W. Bush from 2001-2009 he plotted to assert himself from the sidelines. In an early scene, after going through a Congressional internship, he is given his own office in Washington. It’s a depressing, windowless closet, but Cheney is thrilled and calls his wife Lynne (Amy Adams) to report in.

As we later learn, one reason for his reticence in running for an elected office was the scrutiny involved in his private life after his youngest daughter Mary (Alison Pill), comes out. To his credit, and this is perhaps the only time when Cheney becomes human, he does not use gay-marriage as an issue on the campaign trail.

There is a telling scene when Cheney asks a fellow intern what party the speaker they have just heard is from. Cheney immediately claims allegiance with that party based on nothing more than the speaker’s presentation. The speaker is conservative Illinois congressman Donald Rumsfeld (a one-dimensional, but sufficiently dodgy Steve Carell) and for the first half of his career, Cheney ties himself to Rumsfeld’s wagon. This ‘any-way-the-wind-blows’ attitude works.

Together the two plot to fill the power vacuum in the White House under Gerald Ford when Nixon resigns and Rumsfeld becomes Secretary of Defense. Cheney becomes the youngest Chief of Staff in history (1975-1977), but Ford’s scathing condemnation of both Rumsfeld and Cheney came too late. Cheney was a five-time elected representative of Wyoming (a position his eldest daughter inherited after coming out against gay marriage to keep Wyoming in the family).

As Secretary for Defense under George H.W. Bush, Cheney oversees Desert Storm, but the real damage is done under his son (Sam Rockwell, fabulous). Cheney at first declines the VP role because Lynne looks down on what she perceives as a thankless, dead-end job. But it’s the one Cheney wants, particularly after reaching an understanding with George – who is more interested in a barbeque on the lawn than masterminding the retaliation for 9/11 – that he will run the show.

McKay fleshes out each major position on Cheney’s CV with quickly edited sketches of policies he introduced including efforts to scrap the estate tax (known as the ‘death tax’). But surely a $2 million allowance before estate tax has to be paid helps the middle classes and not the rich whose properties are worth much more. There are many people living in properties worth £1.5 million in the UK (as in the USA) who are asset rich and cash poor and would have to lose their homes to pay the tax. Cheney did real damage to broadcasting, however, but that is skimmed over so that not many Americans, let alone British audiences would understand.

McKay turns to the Unitary Executive Theory (that gives the President regal powers) for a laugh. But contrary to Mckay’s claim that Supreme Court Judge Antonin Scalia helped Cheney consolidate power as a co-President by backing the Unitary Executive Theory, Scalia defended the separation of powers in a major court case.

The farcical treatment of Cheney’s politics (right down Colin Powell’s (Tyler Perry) humiliation when forced to lie about his view of reports on weapons of mass destruction) is fodder to the liberal audiences, eager for some therapeutic (and deserved) collective Cheney bashing. But it will be more difficult to get any conservatives on board as McKay never reconciles the monster with the man.

With the exception of Cheney’s involvement in the Halliburton Company, where he was CEO in between White House positions from 1995 to 2000, we never learn what motivated the man. Curiously Mckay sidelines all the proof that Halliburton benefitted from military contracts under the Cheney/Bush regime or from oil field in Iraq, although we do hear him acknowledge a cheque for $26 million when he divests his holdings to become VP. Cheney is happy fly fishing; is money really his motivation?

And long before Halliburton, where did Cheney, who began his adult life with an anger management and alcohol problem, flunked out of Yale and took a job installing up telephone lines, get his ambition? As we see in a terrific early scene, when Cheney returns home drunk one day, Lynne, then his pretty fiancée, gives him an ultimatum that changes his life. Either he shape up or she will marry someone else. Realising that Lynne is going places without him, he complies.

We have here, of course, a ready-made modernisation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. McKay must realise that, particularly with a telling bedroom scene, but he fails to structure the film along these lines, despite having a great Lady Macbeth in Adams.

When we do see Lynne, it is she who is giving her husband encouragement, stern advice and some glaring looks, particularly when he mentions ‘Vice’ President. Lynne is not as comfortable with second best. As she makes her way up the NGO and charity ladder she is an asset, admired by both Rumsfeld and George HW Bush.

Lynne’s roll decreases as the movie goes on, which is a shame. For the only plausible explanation is that it is Lynne who is driving Dick. Cheney might have been unwilling to hurt Mary, but Lynne never encountered a personal issue that could not be compromised for power and political advancement.

You can watch the film trailer here: