Joyce Glasser reviews Uncle Howard (December 16, 2016)

In her New York Times review of film director Howard Brookner’s film Burroughs: the Movie, Janet Maslin wrote: ‘Rarely is a documentary as well attuned to its subject as Howard Brookner’s Burroughs, which captures as much of the life, work and sensibility of its subject as its 86 minutes allows. But the quality of discovery about Burroughs is very much the director’s doing.’ To some extent, the same can be said of his nephew Aaron Brookner’s Uncle Howard, a tribute to the uncle who inspired his career, but who died of AIDS in New York City, where he was born, aged 35.

In the production notes, Aaron claims that, along with restoring Burroughs: The Movie in a new digital print, making the documentary was a way of keeping Howard’s legacy, and his memory, alive. Like Nathaniel Kahn’s great documentary, My Architect: A Son’s Journey, about the celebrated American architect Louis I Kahn, Aaron’s film begins as a search.

In the production notes, Aaron claims that, along with restoring Burroughs: The Movie in a new digital print, making the documentary was a way of keeping Howard’s legacy, and his memory, alive. Like Nathaniel Kahn’s great documentary, My Architect: A Son’s Journey, about the celebrated American architect Louis I Kahn, Aaron’s film begins as a search.

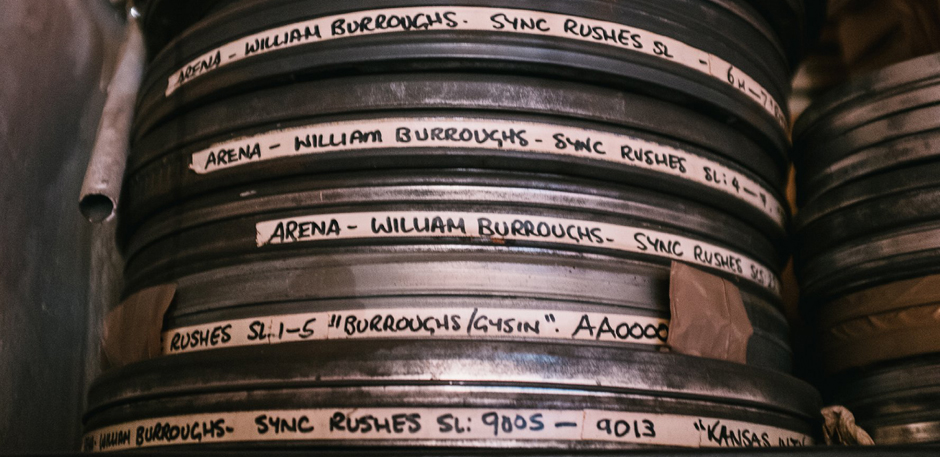

In this case, it is the rescue of a long forgotten archive in the Bunker: the former home of beat generation guru and author of The Naked Lunch, William S. Burroughs. The Who’s Who of Manhattan’s counterculture scene once passed through the neighbourhood or through the door. It is now the home of poet John Giorno who was reluctant to let Aaron in. Aaron solicited the help of James Grauerholz, Burroughs’s friend, business manager, editor and, eventually, the literary executor of his estate (Burroughs outlived Howard by ten years).

Grauerholz is one of many talking heads who supplement the archival footage, Howard’s video diary and Aaron’s narration to complete the portrait. ‘Burroughs was suspicious…’ Grauerholz tells Aaron, ‘but he found something in Howard – mischievous, interested, knowledgeable and fun to be with…He trusted Howard.’

Grauerholz comments, ‘I have never felt Howard was dead and gone. Howard’s was an unfinished story and that giant pile of film in the Bowery in the Bunker held so much of his spirit.’ Seeing the Bunker again ‘freaks out’ Jim Jarmusch who recorded sound on Burroughs: The Movie (and co-produced this one). He went on to become one of America’s most prolific and admired independent filmmakers.

For Tom DiCillo Howard’s cinematographer on Burroughs, (who went on to direct Living in Oblivion), watching the footage he shot of Burroughs in the Bowery in 1979 is a nostalgic, bitter-sweet experience. DiCillo reminisces about the heyday of independent cinema, attributing their liberation to Burroughs. It is not only seeing old friends again: from Alan Ginsberg to Patti Smith – a who’s who of the cultural scene. The Bowery, and nearby no-go zone, Alphabet City, have changed and are now gentrified parts of the East Village in lower Manhattan. Later on in the film Aaron laments the disappearance of St Vincent’s Hospital and the Chelsea Hotel, two other landmarks he associated with his uncle. All those memories were fading.

Stewart Meyer, Burroughs’ protégé, and author of The Lotus Crew a raucous, gritty, darkly comic novel about heroin addiction, remembers that the first time he scored off the Bowery on Rivington Street was with Howard. Aaron learns that Howard’s risk taking extended beyond filmmaking to hard drugs and frequenting gay bars and nightclubs like Heaven.

Like his uncle’s film about Burroughs, Aaron covers Howard’s family life, personal life and his work. Howard’s parents wanted him to be a lawyer and have children. His mother, Elaine (whose testimony is particularly poignant), was afraid that Howard’s boyfriend, Brad Gooch, ‘would be some older man taking advantage of my young son. Then he got off the plane and there was this young, gorgeous man.’ Brad tells Aaron that Elaine never really accepted Howard’s homosexuality, even suggesting that he see a doctor to change his sexual orientation. With the success of Burroughs, however, she did finally accept his career choice.

In Howard’s second documentary, Robert Wilson and the Civil Wars, he follows the avant-garde theatre director’s attempt to stage a twelve-hour, multinational epic for the 1984 Summer Olympics in L.A. Howard’s schedule was as exhausting as Wilson’s. There is some foreshadowing here, too, as Wilson’s race against the clock to finish the opera for the Olympics is later mirrored in Howard’s attempt to finish his first feature film, The Bloodhounds of Broadway, before his death.

Howard persuaded David Puttnam, then at Columbia Pictures in Los Angeles, to finance the film and lured the then A-list talent, Matt Dillon, Jennifer Grey, Rutger Hauer and Madonna into starring roles. Co-producer Lindsay Law tried to warn Howard about undertaking such an ambitious, complicated production for his first film. And just before the start of principal photography Howard learned that he was HIV positive. Rather than slow down, Howard went with little sleep, filmed in the snow, and went off his AZT medication (which prevented him from focussing) to finish the film. Only Brad knew that Howard was dying.

Howard did finish the film, but did not live to see its release — and negative reviews. Sadly, he did live to learn that Columbia was re-editing the film and introducing a narrator. Uncle Howard includes no references to this, or to the negative reaction of audiences and critics. Despite his loss of vision in one eye, Howard was planning an adaptation of Brad’s book Scary Kisses just before his death and keeping a video diary — his final footage. Aaron remembers learning the news that his uncle was dying. ‘I knew it was a sad thing, but nothing felt sad around Howard’.

At times the lack of transitions between speakers or locations might leave the viewer confused. The exterior of the Hotel Louisiane in Paris where Howard would stay, for example, suddenly becomes an interior hotel room where a woman captioned as Kim Massee is looking over photos and describing her relationship with Howard as ‘passionate.’ Not everyone will know that Massee is a French actress who began writing and directing – although after Howard’s death. What was their relationship? Some context would also have helped to explain where Frédéric Mitterrand, the former French Minister of Culture –full of praise for Howard – fits in.

Aaron ends the film with Howard’s posthumous letter to his parents, a letter so generous, so positive and so beautiful that it will leave you weeping. That letter tells you more about the kind of guy Howard was than anything else in a truly moving film.

You can watch the film trailer here: