Joyce Glasser reviews Whitney: Can I Be Me (June 16, 2017), Cert. 15, 90 min.

This absorbing and comprehensive documentary biopic completes our knowledge (probably to the extent possible) of the rise and tragic fall of Whitney Houston, who died in the bathtub of her suite in the Beverly Hilton Hotel of cocaine and coronary artery disease in 2012, aged 48. The title of Nick Broomfield’s documentary is a question Whitney could answer any more than we can after seeing the film. For Whitney Houston was a mix of nature, nurture and the same dizzying and deleterious rise to fame that changed and then consumed Amy Winehouse.

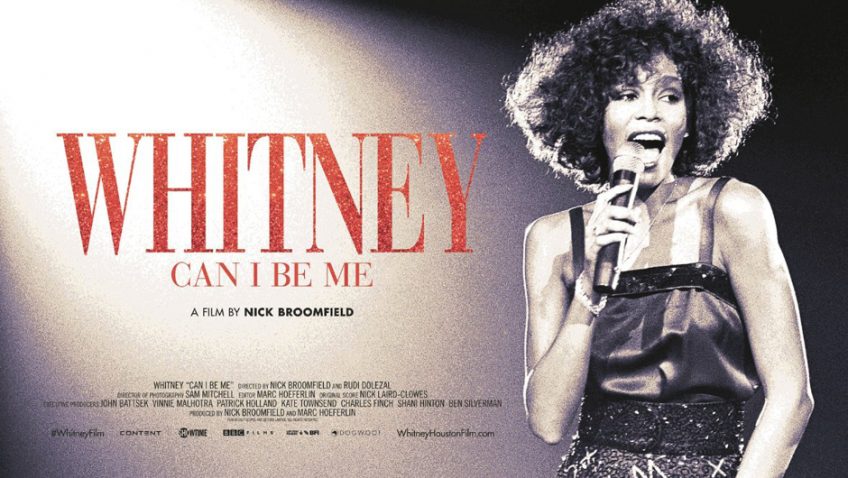

Whitney: Can I Be Me

is not a typical Nick Broomfield film, although he has delved into the tragic edge of the music world with Kurt & Courtney. A former BBC filmmaker, Broomfield is best known for barging into rooms like a grubby, pushy, resident American P.I. looking under the bed for conspiracy theories and the truth in high profile cases of criminal activity (Ghosts); abuses of justice ( Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer) and sleazy relationships (Heidi Fleiss: Hollywood Madam).

Whitney: Can I Be Me is less personal and idiosyncratic. Broomfield remains strictly behind the camera and one step removed from the – what is now – fairly conventional Shakespearean tragedy that unfolds. This might be because he co-directs here with the well-connected Rudi Dolezal (Freddie Mercury, the Untold Story) a producer/director who worked with the Rolling Stones for over two decades.

Born in Newark, New Jersey in 1963, Houston was not brought up illiterate in a one-room slum in poverty, but in a largely black, but middle-income neighbourhood where she became a soloist in her mother Emily ‘Cissy’ Drinkard Houston’s gospel choir. Cissy, a former professional singer, and her father, John, an ex-Army man turned-entertainment executive, were quick to get behind their daughter’s talent. Every one knew that Whitney’s first cousin was Dionne Warwick and that her mother recorded with Aretha Franklin (who became Whitney’s ‘Honorary Aunt’). When Whitney was four the family moved to a better neighbourhood in East Orange, New Jersey following the racially-motivated Newark Riots. But it was 1967 and Whitney shared her brothers’ drugs because ‘that’s what you did to have fun.’

Once the drug habit is introduced, it’s not long before the influence of the parents has to be considered in answering the title’s question. Cissy seems to have been a controlling, credit-grabbing mother who kept a strangle-hold on her daughter’s career for as long as she could. We are told Whitney was closer to her father, but in a rather sketchy chapter toward the end of the film, it seems like John was more interested in his daughter’s money than in her well-being. If there is controversy about whether Mitch Winehouse exploited his daughter, there is little doubt that Whitney put a large number of family members on the payroll to prevent them from begging at the table.

Another factor in Whitney’s identity issues was racial identity. In 1985 Whitney became a megastar with the release of the world’s best selling debut album, Whitney Houston, followed by ‘Whitney

’ that sold close to 30 million albums two years later. With looks to match her voice, she was a glamorous crossover presence on all the mainstream talk shows, and, most people thought, a great black role model.

But on March 30, 1988 at the second annual Soul Train Music Awards in L.A., she was booed for selling out to white audiences. This was a life-changing shock for Whitney and, the film suggests, might have motivated her sudden infatuation that evening with the younger, teen idol and ‘bad boy of rhythm’, Bobby Brown. ‘Bobby was street’ we are told, and a rapper with whom black youth identified. For Bobby, Whitney supplied the class and a major spot in her next big, lucrative tour.

In 1993 Houston looks sensational on the Barbara Walters Show. She is married, has a baby (the ill-fated Bobbi Kristina Brown) and is happy. But was she? The film suggests that Bobby Brown was a destructive force similar to Amy’s ex-husband Blake Fielder-Civil. Apparently, Brown was unfaithful, abusive and an alcoholic. He supplied the booze, but she supplied the drugs to which she remained addicted.

Sexual identity might be another reason why it was so difficult for Whitney to have been herself or even have known who she was. As a teenager at Mount Saint Dominic Academy, a Catholic girls’ school, she met Robyn Crawford. Whitney described Robyn as the sister she never had, but throughout most of Houston’s adult life Robyn served as a protector, confidante, private secretary and sounding board. It is never stated that the two had a sexual relationship, but until Whitney’s marriage the two women were inseparable. The real difficulty for Houston was that until Brown issued an ultimatum forcing Whitney to choose between Robyn (whom he despised, and vice-versa) and him, she continued to depend on Robyn.

Whitney Houston was, the film asserts, trapped in her stardom. She branched out with equal success into film with The Bodyguard and Waiting to Exhale, ironically about four black women “holding their breath” until they can be in a committed relationship with a man. The more she earned, the more she travelled, took drugs and worked and the harder it was to be a mother and lead a normal life.

The film lacks the poetry, visual narrative and, critically, the amount of unseen footage and singing of Asif Kapadia’s Amy, but remains an impressive accomplishment. This is especially the case considering that the filmmakers seem to have obtained the cooperation of Houston’s and Brown’s family without shying away from the candid comments of her real life body guard or creating a neutered ‘official’ biopic. Houston seems to escape any blame (her daughter self-destructed at age 22) although in any tragedy the victim contributes to the fall. Unfortunately, too, we do not hear directly from Brown or – and this is the film’s most conspicuous shortcoming – from Robyn Crawford. Still, you can imagine the legal hurdles the film’s producers had to jump without that.

You can watch the film trailer here: