Joyce Glasser reviews Destination Unknown (June 16, 2017) Cert 12A, 79 minutes

Seldom, if ever, has a 79-minute film packed in so much emotion, horror, repulsion, suspense, historical revelation, courage, hope and love. In a fictional film, this would be foreboding, if not impossible; but Destination Unknown is a riveting documentary and a very rare and important one at that.

Claire Ferguson’s film does not focus on the dead, but on 12 survivors. By the time you see the film, those witnesses were still alive when the film was made might no longer be with us. Their testimonies, however, and the powerful archival and personal footage that Ferguson has compiled, can, and must, never be forgotten.

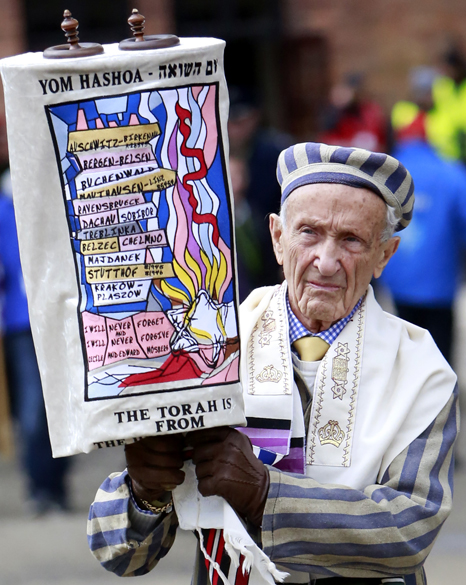

Ed Mosberg (who will be at a Q & A with the Ms Ferguson at the Curzon Soho, Shaftesbury Avenue, on 16th June) puts on the stripped prisoner’s uniform from Mauthausen-Gusen in Upper Austria. ‘I was born in Krakow, Poland in 1919… Parents, two sisters, uncles and cousins: I am the only survivor.’ Mosberg wheels his wife Cesia, who lost her family in the Holocaust, to a remembrance ceremony. [My wife] will tell you I never left,’ he says. ‘I feel the pain every single day.’

Ed Mosberg (who will be at a Q & A with the Ms Ferguson at the Curzon Soho, Shaftesbury Avenue, on 16th June) puts on the stripped prisoner’s uniform from Mauthausen-Gusen in Upper Austria. ‘I was born in Krakow, Poland in 1919… Parents, two sisters, uncles and cousins: I am the only survivor.’ Mosberg wheels his wife Cesia, who lost her family in the Holocaust, to a remembrance ceremony. [My wife] will tell you I never left,’ he says. ‘I feel the pain every single day.’

The persistence of memory unites the individuals. ‘I could forget what I ate for breakfast this morning, but I will never forget what happened for the five-and-a-half-years in the concentration camp,’ Marsha Kreuzman says of the nightmare that was Mauthausen. She told the American soldier who freed her that she wanted to die.

The film begins with an introduction to each of the 12 survivors. We see a photograph from their youth and then hear from them briefly as adults. When Ferguson intercuts between the longer stories, you might get a bit confused trying to remember who the person is and where that person’s story had paused.

The testimonies, however, are extraordinary in their quiet dignity, anger and sorrow. Frank Blaichman, who was one of the rare resistance fighters to survive the war, never stops asking himself: ‘Did I do the right thing? I left my family. Now I’m alone.’

Other stories are so romantic that no dramatist could compete. ‘Close friends’ Victor and Regina Lewis were separated as teenagers when their respective families were herded out of the Plac Zgody in Krakow at the liquidation of the ghetto in 1943. In the train to their unknown destination (Treblinka) Victor told his family: “We are going to the gas chamber. I’m cutting the bars so I can jump.’ He continues: ‘I asked my family to follow me. My father said: ‘If you can save yourself, then go ahead. But I am too old to run.’ Victor then ‘jumped into the night.’

If Eddie Weinstein’s daring escape from Treblinka was equally courageous, there’s nothing in Casablanca or Dr Zhivago as romantic as Regina’s reunion with Victor. But there is another incredible reunion story in Destination Unknown.

Stanley Glogover had last seen his father in Auschwitz where they were assigned separate barracks. His father had been beaten so badly he could not work. Prisoners in that condition were routinely sent to the gas chambers. In late 1945, Glogover hardly felt jubilant in a displaced person’s camp. ‘All my family’s gone…I’m a young kid…I have to find somebody I can be with.’ Glogover’s search for that somebody is an adventure story that you couldn’t make up. ‘I went to every concentration camp in Germany,’ he tells us. There was a Glogover on one of the lists, but as there was no first name, he could not be sure it was not his own. He followed the trail over the Carpathian Mountains to Austria only to learn that the prisoners had been transferred to Italy. After searching ‘from city to city…sleeping in the parks on benches,’ he met a gypsy who predicted, ‘You will find someone here who was close to you.’ There’s no spoiler here, but you will want to know if the fortune teller was right.

Eli Zborowski escaped the concentration camps by hiding in barns, attics and basements with his family. Standing in one of those claustrophobic hideaways he reflects on the courageous people who sheltered them. ‘These people were angels, not human beings. If it couldn’t be for a few people like them then you’d think there is no humanity at all.’ Later in the film Mr Zborowski shares with us a memory that he has always kept a secret. ‘At the end of the war I volunteered with the Polish Army to fight the German Army.’ On a mission with the Russians, an angry Russian general vowed to shoot a German they captured in order to avenge his grandmother’s murder. When a German PoW was dragged before them, Zborowski, who was ‘just 18 or 19’, was asked to translate. ‘Somehow I felt he doesn’t deserve to die. I translated whatever I felt it should be to save his life.’

‘I became the camp writer for Amon Göth against my will,’ the late Mietek Pemper tells us, referring to the infamous Austrian commandant of the Kraków-Płaszów concentration camp. Helen Steinlicht also knew Göth first hand when he chose her to be a cleaner at his villa. As we watch archival footage and photos of a fat, bare-chested man holding a rifle in one hand and cigarette in another, she tells us that ‘he was enjoying shooting people from his balcony. People were falling like cockroaches.’ He also trained dogs to tear Jews apart. While the prisoners were starving metres away, Steinlicht served guests at Göth’s boozy dinner parties.

Both Pemper and Steinlicht had the good fortune to meet one of Göth’s frequent guests: Oskar Schindler. Pemper went on to compile the famous lists. Helen recalls Schindler asking her if she remembered the story of the Jewish people in Egypt. ‘This is what will happen to you. You will see. You will be free…’ Helen’s husband, Joseph, whom she met at Schindler’s factory in Brünnlitz in the Czech Republic, could never be free. After they raised a family together, he committed suicide.

Pemper, a witness at Göth’s trial, outlived the 37-year-old butcher by 65 years. Eddie Weinstein’s revenge came in a different manner. ‘When the war ended, we raised a family,’ he says as we watch home movies and photos of his family. ‘Two sons and 7 grandchildren.’ We see a photo of the proud grandfather holding a cute little girl in a bathing costume. ‘They are my answer to Hitler’s final solution.’

You can watch the film trailer here: