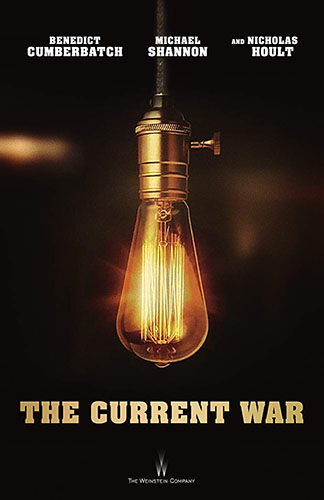

Joyce Glasser reviews The Current War (July 26, 2019), Cert. 12A, 108 min.

You can understand why Martin Scorsese, credited as Executive Producer of The Current War, would see the battle between a brilliant, petulant and hyperactive inventor and a smart and tempered industrialist over the monopoly of U.S. electricity as dramatic, exciting and cinematic. Scorsese has an interest in male-dominated stories of heroes and colourful anti-heroes and in cinema history. The lead character in The Current War is Thomas Edison (Benedict Cumberbatch) who patented an early film camera, made dozens of short films and was a contemporary of French film maker George Jean Méliès, the subject of Scorsese’s 2011 film Hugo. The trouble with The Current War is that it isn’t directed by Scorsese, but is made by a director and writer who clearly lacks Scorsese’s and Edison’s visionary genius.

Director Alfonso Gomez-Rejon, (Me and Earl and the Dying Girl) and playwright Michael Mitnick (the disappointing adaptation, The Giver) provide good character studies of two competitive inventors and they capture the period look handsomely, from the costumes to a variety of late 19th Century American interiors, from palatial homes and laboratories, to hotel carriages to modest hotel rooms. But they never find the drama, the spark or the metaphorical resonance in this heavily-captioned story.

Director Alfonso Gomez-Rejon, (Me and Earl and the Dying Girl) and playwright Michael Mitnick (the disappointing adaptation, The Giver) provide good character studies of two competitive inventors and they capture the period look handsomely, from the costumes to a variety of late 19th Century American interiors, from palatial homes and laboratories, to hotel carriages to modest hotel rooms. But they never find the drama, the spark or the metaphorical resonance in this heavily-captioned story.

The first hour of the film seems a lot like school. Captions provide some essential information and then, for the next hour, you are bombarded with a history lesson full of scientific and technical jargon uttered in an urgent and excitable manner primarily by two men Thomas Edison (Cumberbatch) and George Westinghouse (Michael Shannon) in the vanguard of progress. To their credit, very little of this dialogue is written in an expository manner, but it is not exactly engaging either.

We know that the stakes are high, and we will gradually get to know the two protagonists enough to see how their personalities, and, to some degree, their wives, play a key role in their momentous decisions. But to understand what is at stake and appreciate the obstacles both men face, you would be advised to read up on the current wars if your knowledge of American industrial history is rusty. The term AC/DC is more familiar today as a slang word for bisexual than for its original meaning, which is the fundamental difference in approach between Edison and Westinghouse.

When the film opens both Westinghouse and Edison are travelling in trains, the invention that was extending the country and creating a huge demand for hydraulic plants to generate Edison’s DC (direct current) power system. It is 1880, four -years after Edison moved into his industrial research lab in Menlo Park, New Jersey and the press arrives to witness the park alight with bulbs. The film does not really give us an idea of how ground breaking this giant man-cave was, but it no doubt inspired Edison’s quote, ‘to invent, all you need is a good imagination and a pile of junk.’

Many of the patents Edison claimed were his were invented by others, as he employed many talented men (and a few women). One employee was his first wife, Mary Stilwell Edison (Tuppence Middleton) who was 16 (he was 24) when they married. They had three children before Mary died of a brain tumour, age 29, in 1884. In one early scene we see Edison communicating with his son, Thomas Jr. in Morse Code so a family joke would not be understood by its object. The children soon drop out of the picture and Edison’s second wife never enters it. Another employee was Nikola Tesla, a 28-year-old Serbian immigrant who went on to be a competitor in his own right, and then as an employee of George Westinghouse. Westinghouse, too, exploited the hapless Tesla for his patents, but did not, as Edison did, dismiss Tesla’s faith in A/C power as “utterly impractical.”

Edison invented the incandescent light bulb and, backed by the banker JP Morgan (Matthew Macfadyen) he had an early lead in the current war where his direct current system was shown to work in crowded cities. But the United States was a huge, and in 1880, still largely rural country with huge distances to cover. It was both cheaper and more practical to use alternating current, as Tesla advocated, but Edison had too much invested in DC to see it.

By 1887, within a year of adopting the AC system, Westinghouse had overtaken Edison’s early lead. Westinghouse at one point hints at working with Edison, but Edison was not only an optimist, but independent and very proud as suggested by his quote, ‘I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.’

The problem for Westinghouse is his awareness of his limitations, his inclination to forge alliances rather than rivalries, and his strength in marketing and seeing the big picture rather than invention. When, at one point, Westinghouse decides to give up the race, his wife, Marguerite Erskine Walker Westinghouse (Katherine Waterston), ensures that he heed his rival’s saying, ‘our greatest weakness lies in giving up. The most certain way to succeed is always to try just one more time.’

Both men are ruthless when they need to be, and both use the press, exaggerated information and dirty tricks campaigns to gain an advantage in their war to provide the lighting for the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

In order to discredit the Westinghouse system, Edison demonstrates to the press how dangerous it is by putting a horse in contact with an AC circuit. This works for a while, but it comes back to haunt Edison when an enterprising New York dentist, who is, like Edison, against capital punishment, approaches “the wizard of Menlo Park” to develop a more humane way to execute the contrite wife killer William Kemmler (Conor MacNeill).

In the experiment, the press note how swiftly and quietly the horse dies (this experiment is widely repeated). Surely the man who claimed that Westinghouse would kill a customer within 6 months of the installation of a sizeable system could use that system to humanely kill a man?

There is huge potential and topical interest in this subplot, but the drama inherent in this, as in the rest of the story, is buried in the lame exposition and lacklustre script. The filmmakers are so obsessed with getting through the material that they forget their job is to tell an engrossing, relatable story. When the news of Edison’s death was announced in 1931, communities all over the world dimmed their lights or disconnected their power as a tribute and to mark the loss to the world. That is the kind of visual prompt filmmakers use to create emotion, but here that emotion is once again bottled up, this time in a caption that imparts the information.

You can watch the film trailer here: