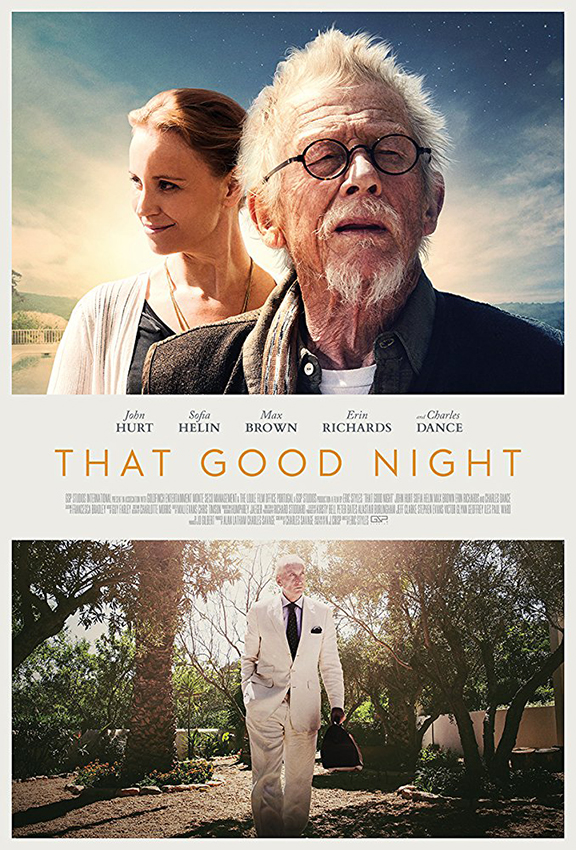

Joyce Glasser reviews That Good Night (May 11, 2018) Cert. 12A, 92 min.

Too early in writer Charles Savage’s film adaptation of N.J. Crisp’s 1996 play That Good Night, terminally-ill novelist and film script writer Ralph Maitland (John Hurt) is given a lethal injection by a mysterious ‘local man’ (Charles Dance). He is later discovered by his long-suffering younger wife, Anna (Sofia Helin) lying by the pool on their hill top terrace in the Algarve where 95% of the film takes place. Fortunately, in Eric Styles (Relative Values) otherwise pedestrian adaptation, Maitland, as we suspect, is not dead. Sadly, though, this is not a case of art imitating life, although John Hurt, who died last year at 77, knew of his own terminal illness when he took on this role. And Hurt, like Maitland, is given a final chance to shine in his striking scenes with Dance, six years his junior.

Upon receiving his terminal diagnosis, which he calls, ‘the ultimate deadline,’ Maitland summons his semi-estranged only child, Michael (Max Brown) to the Algarve. Summons is the operative word as Michael tries to protest that he has a conference to attend in Seville, but his father is not interested. ‘I have a decision to make,’ he tells Michael as though that is a rare and sacred event.

Upon receiving his terminal diagnosis, which he calls, ‘the ultimate deadline,’ Maitland summons his semi-estranged only child, Michael (Max Brown) to the Algarve. Summons is the operative word as Michael tries to protest that he has a conference to attend in Seville, but his father is not interested. ‘I have a decision to make,’ he tells Michael as though that is a rare and sacred event.

Maitland intends to tell Michael the news, but has kept it a secret from his wife. Perhaps he wants to avoid the fuss. Or it could be because Anna was Maitland’s nurse when he was in the hospital for a heart condition (which is how they met), and he wants to spare her another caring role. That theory assumes that Maitland extends that degree of consideration to others, which is not an assumption we can make after five minutes in the presence of this cynical, self-absorbed old man. When the doctor asks him, ‘how are you,’ Maitland is the kind of guy who answers, ‘if I knew that, I wouldn’t be here.’ In fact, as Maitland seems to do nothing more than sit at his desk and, encouraged by Anna, take his prescribed medicine and exercise in their pool, she has never stopped being a carer.

The unannounced arrival of Michael’s girlfriend Cassie, (Erin Richards) who temporarily works as a conference hostess, brings out the worst in Maitland. When Michael brags that Cassie has a PHD in Social Anthropology – focusing on the reconstruction of cultural Heritage after conflict – Maitland replies, ‘you know, that sounds mind-numbingly boring.

If Maitland takes an instant dislike to Cassie, it is not only because she is interrupting his time to get his home in order before his death. His verbal attacks on Cassie are so acerbic and nasty that they hint at something personal. Digging like a terrier at her statement that she is a hostess, he reasons that, euphemisms, aside, she is paid to be nice to men – insinuating that she is a prostitute. Refreshingly, Cassie can give as good as she takes and we can derive much pleasure from watching Hurt’s facial reaction when he realises he has gone too far, but cannot recall his words.

It is only after a brief altercation between Maitland and Anna after Michael announces that Cassie is pregnant that we have our clue. If it seems terribly convenient, the news at least serves to push the stagnating story forward.

We realise that Cassie must remind Maitland of his first wife, whom he claims plotted to trap him through her pregnancy (the result being Max). Too selfish, perhaps, to compete with a child for his wife’s attention, or too distrustful to fall for a woman’s subterfuge again, he refused to give second wife, Anna, the child she craved.

Just over half-an-hour into the film Maitland is seated in his dark, but handsome office, when he receives the first of three visits from a tall, elegant man (Dance) in a white linen suit (identified in the closing credits as The Visitor). We are not meant to know whether The Visitor is a representative of a exclusive, secretive Euthanasia Society or the personification of Death, but anyone who has seen JB Priestley’s An Inspector Calls probably has a clear idea.

Maitland wants to die and The Visitor’s job is to ensure that all other options are explored and discussed before the client goes gentle into that good night. Yes, at several points in the film Hurt turns to poetry recital, first with profound words from Yeats (the centre will not hold) and then with this powerful, but overused Dylan Thomas staple that has replaced the Wordsworth’s Daffodils as the best poem ruined by its inclusion in the school curriculum (and in screenplays).

Despite the grim subject matter, when Hurt – dishevelled, wrinkled and raspy-voiced and Dance – suave, soft spoken and immaculate – are dancing around one another in a delightful intellectual game of one-upmanship, the film is raised to another level. One that we do not reach again until Dance’s next, significantly shorter, visit.

The dialogue outside of these magical encounters is not worthy of a film about two scriptwriters. Michael tells his father that after a conference he is organising in Seville, he is going to Malaga for a new co-production of a drama called Midnight Cavalier. We’ve all fallen asleep during similar dramas. Maitland is nonetheless convinced that his son has inherited his talent. ‘You don’t have to do that crap,’ he pleads with Michael, although at this point we are not totally convinced.

The film cries out for a major confrontation with a wounded Anna when she discovers that Maitland is suddenly, and uncharacteristically, thrilled with the prospect of a grandson to carry on his name. Her resentment at her husband’s betrayal and selfishness seems to pass by like an upset stomach when it must be at the crux of the drama. But none of the other characters get much of a look in, which is just as well. Max Brown’s Michael only seems real when we discover that he is a producer of Euro-pudding co-productions like this one.

You can watch the film trailer here: