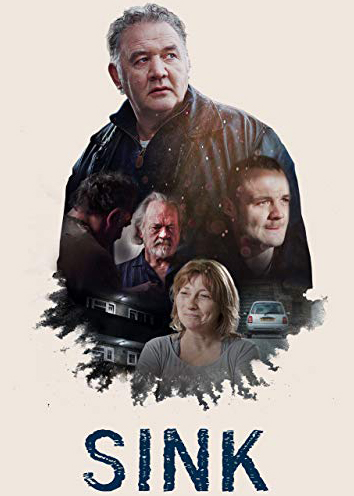

Joyce Glasser reviews Sink (October 12, 2018), Cert. 15, 85 min.

The myth perpetrated by the media and certain ministers and MPs secure with their generous final salary pensions or seats on some corporate board, is that everyone over 60 has had it too good and is selfishly robbing the young of their future. For this reason alone, actor turned writer/director Mark Gillis’ low budget, British character-driven film Sink, is a breath of fresh air. Sink is about an affable, hard-working and principled single father of around 60 who is too young to retire and deemed too old to compete with the ‘energetic and bright’ – i.e. younger – candidates. Sink has the disadvantage of resembling a nonpartisan, anaemic version of Ken Loach’s 2016 film I, Daniel Blake, one of the most hyped and promoted British films of the millennium.

Micky (Martin Herdman) is one of a growing number of people between 50 and 75 who are plagued by dependents from two generations. His son Jason (Josh Herdman) is a good person at heart but can’t seem to make an honest living and has returned to drug use after going clean. Micky’s father, Sam (Ian Hogg) has dementia and Micky can no longer afford the fees of the private care home where Sam has been happy. After visiting the council’s care home and deciding that it is not fit for purpose, Micky takes his dad home to his bedsit on a council estate.

Micky (Martin Herdman) is one of a growing number of people between 50 and 75 who are plagued by dependents from two generations. His son Jason (Josh Herdman) is a good person at heart but can’t seem to make an honest living and has returned to drug use after going clean. Micky’s father, Sam (Ian Hogg) has dementia and Micky can no longer afford the fees of the private care home where Sam has been happy. After visiting the council’s care home and deciding that it is not fit for purpose, Micky takes his dad home to his bedsit on a council estate.

While Sam doesn’t complain, everyone else, including Mickey’s super is aware that a bedsit is too small for the two men. And just when things couldn’t get worse, Micky is laid off from his factory job with only one day’s pay as compensation. The way in which Micky is made redundant with no notice and without the due process required by law suggests he was on a zero hour contract, but it’s curious.

Why Micky does not have a steady PAYE job and just where photos from a boxing career or hobby (for both Jason and Micky) come in to the story are two questions that are not really answered. Nor do we ever find out why next-door neighbour Jean (Marlene Sidaway) is happy to volunteer taking care of Sam all day long, particularly when he is dangerous enough to point a gun to her head.

Gillis seems more concerned with examining how society drives an good man to compromise his principles and turn to criminal activity.

The insecurity surrounding Micky’s home life is matched only by the difficulty he encounters – or envisages he will encounter – in finding a new job. Although he is offered a position as a driver/deliverer on his first interview, his future boss discovers that Mickey has too many points on his licence to get insurance. Two of the points are due to come off in two months, but the employer cannot wait.

But unlike Loach in I, Daniel Blake, Gillis is not a polemicist and his criticism of the system is so subtle as to undermine whatever point he is making. Far from being humiliated by cold hearted, sadistic sticklers at the Job Centre, or caught up in the Department of Work & Pensions’ red tape, Micky has no trouble with forms or waiting to be served. And when he is, his adviser gives Micky preferential treatment, sending him on a job interview before the job is officially posted.

The super in his building offers to let Micky and Sam live rent free in a much bigger and fully furnished one-bedroom flat that a tenant has mysteriously abandoned, leaving the rest of the month’s rent paid. Though the super would lose his job if the swap were discovered, it goes ahead, making life a lot easier. We never do learn how it is going to be possible for Micky to get his rent paid by the council when he is not living in that studio flat any longer.

Even the women in his life are nice to Micky. Jean, as already mentioned, takes care of Sam and Lorrain (Tracey Wilkinson) is happy to have occasional sex with Sam, even though it’s been a long time since he was fighting fit.

The man who abandoned the flat where Micky and Sam are living illicitly turns out to be connected with an old friend of Micky. Paul (played by writer/director Gillis) is now a man of refined and expensive taste and a dodgy CV. He likes spending his money to help out an old friend, but expects dividends. When Paul offers Micky a cup of coffee from his new De’Longhi espresso machine, Micky’s self -righteous arguments against Paul’s criminal life grow less convincing. Luxury is addictive.

And even Paul joins the list of people who go out of their way to help Micky. All Micky has to do is drive to France for the weekend posing as a middle-aged woman’s (Sadie Shimmin) husband and bringing back contraband goods.

This is an entertaining, if hardly exceptional first feature film, and if the script is careless the acting is uneven. How, you have to wonder, can Paul offer two people a thick envelope of cash, plus expenses and petrol, just for bringing back some tax free booze and cigarettes? Only drugs hidden in the body of the car would justify such a generous payment, with the booze in the boot there as a decoy.

There was no doubt about what message Ken Loach and his scriptwriter Paul Laverty, wanted to communicate and they did so unabashedly without subtly or nuance in the politicised I, Daniel Blake. What Gillis is trying to say is less clear.

Still it is refreshing that Micky is not a stereotype. He’s a nice guy who has, it seems drawn the short straw once too often, but he’s no saint. For one thing, he’s a hypocrite, yelling at his son for succumbing to the lure of easy money and lecturing Paul on morality only to sink to their level. He’s nervous and penitent about going to France, but finds the ordeal euphoric when it’s over. His illicit gains are not going to go into building a better, more secure life, but into a state-of-the-art coffee machine.

What is curious is that Micky’s resistance fails him long before he had exhausted all opportunities (he only had one interview after all) and when he still had a full contingent of kind-hearted people willing to help him. If nothing else, Jason and Micky are now closer together than ever before: they understand one another.

You can watch the film trailer here: