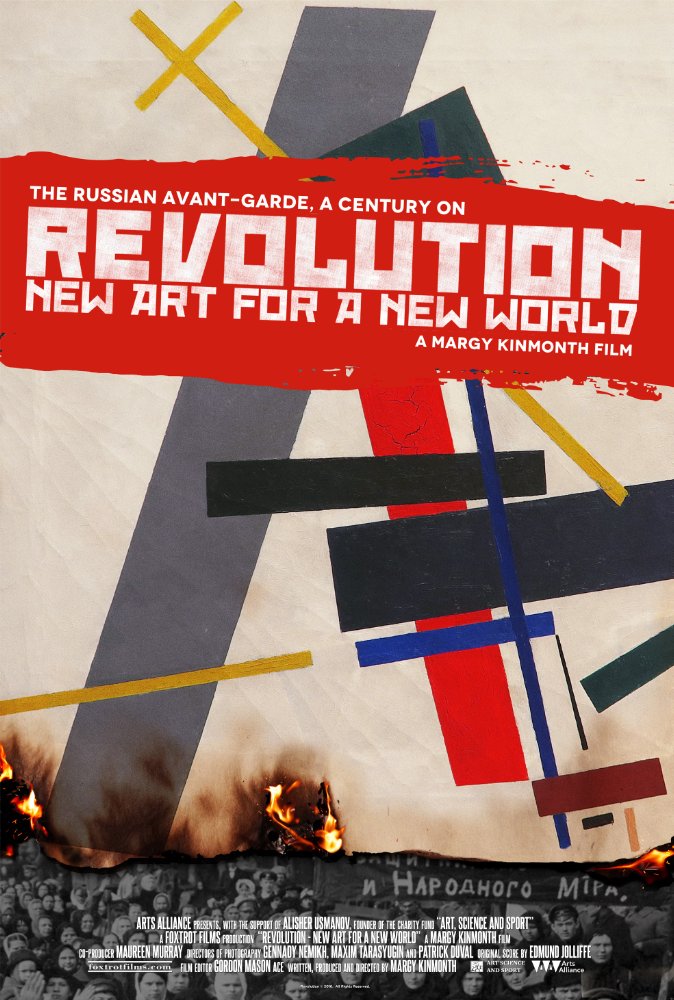

Joyce Glasser reviews Revolution: New Art for the New World (It will be broadcast in the BBC’s upcoming Russian Revolution Season and will air on Monday 6th November 9pm on BBC4)

Politics and art is the subject of Margy Kinmonth’s edifying and vividly researched, if a bit plodding, Revolution: New Art for the New World, jumping the gun on the 100th anniversary of the February, 1917 Russian Revolution. Some of the artists discussed, including Malevich, Rodchenko, Kandinsky, Chagall and Kandinsy have had major exhibitions in London in recent years, but many more are lesser known.

Using a combination of interviews with the descendents of the artists (some of whom are artists and art teachers themselves), Russian museum directors, archive footage and the art works themselves, Kinmonth provides a chronological art history lesson that is bit like being in school, albeit with a very articulate and coherent lecturer. What Kinmonth does so well is place the artists’ work in the context of the political changes in Russian between 1917 and 1930s, substantiating her thesis that politics depended on art to envisage a new order, and art was at the service of politics.

Using a combination of interviews with the descendents of the artists (some of whom are artists and art teachers themselves), Russian museum directors, archive footage and the art works themselves, Kinmonth provides a chronological art history lesson that is bit like being in school, albeit with a very articulate and coherent lecturer. What Kinmonth does so well is place the artists’ work in the context of the political changes in Russian between 1917 and 1930s, substantiating her thesis that politics depended on art to envisage a new order, and art was at the service of politics.

Lenin returned to Petrograd from his long exile in Switzerland to provide leadership in the vacuum created by the February 1917 uprising. Tsar Nicholas II had been forced to abdicate and a weak provisional government was installed in the Winter Palace, the Romanov’s former home (and now, fittingly, the Hermitage Museum).

In his rousing speech, Lenin proclaimed, ‘We need to mobilise the masses to progress fast. Art is the most powerful means of political propaganda for the triumph of the Socialist Cause.’ As Zeifira Tregulova, Director of the State Tretyakov Gallery (Moscow’s National Gallery) reminds us, ‘between 1903 and 1915 Russian art became the most avant-garde in the whole world’. After 1918, Lenin made changes within the leading arts academy, bringing in ‘outsiders’ like Petrov-Vodkin, the son of a maid and a shoe maker, and ensuring that modernism replaced traditional art.

Lenin decided that art was the way to spread the socialist ideology to a largely illiterate population and Kinmonth provides a comprehensive overview of how the avant garde thrived in their role as the aesthetic arm of the Revolution. Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematism of 1916 (art based on geometric shapes), embraced by artist Lyubov Popova, was a revolt against capitalist art and its depiction of material objects. Although it was the Malevich who painted the ‘Black Square,’ Wassily Kandinksy is called the father of abstraction and had his own take on serving Lenin’s revolution. ‘Abstract art places a new world, which, on the surface, has nothing to do with reality, next to the real world,’ he wrote, encouraging people who had lived for centuries under Tsarist rule to imagine an alternative reality.

Artists like Mark Chagall also profited from the Revolution. From 1791 until 1917 Jews were confined to the Russian ‘pale’, but Lenin gave Jews free movement. Chagall was commissioned to decorate his home town of Vitebsk on the first anniversary of the Revolution. His art expressed the triumph of the imaginative over repression – a dream from a small village that is now a reality in a new Russia.

But Lenin’s designs on reality were inevitably manipulative. For all his encouragement of innovative thinking and ideas, Lenin needed propaganda. Mikhail Protrovsky, the Director of the State Hermitage Museum reminds us that Sergei Eisenstein’s famous and influential film October (celebrating Lenin’s Bolshevik triumph over the provisional government) ‘is an absolute lie.’ Lenin proclaimed that ‘the government is tottering; it must be given the death blow’ and he wanted to mark it with a ‘storming of the Bastille’ from the bloody French Revolution. So Eisenstein’s film shows a fictitious storming of the Winter Palace. In fact, the changeover was peaceful and the only damage was the vandalism of portraits of the Tsars.

Nor was Lenin’s reality sustainable. At the end of WWI with Russians starving and even Petrograd lacking electricity, Lenin began a costly campaign of ‘monumental propaganda.’ Old statues were replaced by ‘Street Pulpits’ – statues of revolutionary heroes (including Italian and French heroes as it was too soon to have a sufficient number of Russian heroes). Since bronze was not available during the war, temporary materials were used. Almost nothing of this art remains, but Kinmonth manages to show us some contemporaneous footage that she dug up.

If artists like Kandinsky and Chagall fled during the 1922 Civil War between Lenin’s Red Army and the White Army, others remained to see Lenin implement his reign of terror to prevent a counter revolution. He began a campaign of decorating trains with art and showing films in trains, encouraging cultural values and an appreciation of Lenin, their leader. The famous painter/graphic artist/photographer Alexander Rodchenko created new media to service the revolution represented by his iconic poster of a woman shouting ‘books’, with the letters in the shape of a megaphone.

With Lenin’s death in 1924, Stalin was waiting in the wings to impose his vision of Socialism and his doctrine of how art would be harnessed to serve that vision. Out went the avant garde and modernism – with an unknown quantity of paintings destroyed – and in came Socialist Realism. By the end of the 1930s most artists had fallen victim to the Great Terror and were imprisoned, executed or lived in fear. The celebrated photojournalist Viktor Bulla, whose famous stills of the February Revolution inspired Eisenstein, was accused of treason and shot by a firing squad. The film ends with the fates of dozens of artists scrolling down the screen.

Acknowledging the importance of art in the Russian Revolutionary period, both the Royal Academy and the British Library will be holding major exhibits on the period in early 1917. There is no better preparation than Revolution: New Art for the New World, in selected cinemas on Thursday 10th November for one night only.

You can watch the film trailer here: