Joyce Glasser reviews Rapid Response (September 6, 2019), Cert. 12A, 99 min.

Last week the 22-year-old French F2 driver Anthoine Hubert died in a crash at the Belgian Grand Prix while the previous day, Jessi Combs died trying to beat a 1976 speed record in Oregon’s Alvord desert in her jet-propelled car. These tragic accidents bring topicality to Rapid Response, a documentary about medical improvements in motor racing that, visually, begins and ends with Alex Zanardil’s horrific accident at the American Memorial in Germany in 2001. Tragic as they are, last weeks’ casualties must be compared to the carnage on the tracks in the 1960s, before Dr Thomas Hanna and his protegee, Dr. Stephen Olvey systematically introduced a safety regime into the sport, accompanied by on-site medical experts.

Directors Roger Hinze and Michael William Miles do not purport to offer an objective or comprehensive history of the medical response to racing, which remains to be done. There are others, such as pioneering doctor Henry Brock, who played a key role. Instead they hand the floor to Dr Olvey who narrates, basing his story on his 2006 memoir, Rapid Response: My inside story as a motor racing life-saver

Directors Roger Hinze and Michael William Miles do not purport to offer an objective or comprehensive history of the medical response to racing, which remains to be done. There are others, such as pioneering doctor Henry Brock, who played a key role. Instead they hand the floor to Dr Olvey who narrates, basing his story on his 2006 memoir, Rapid Response: My inside story as a motor racing life-saver.

The visuals come in two categories. Talking heads, both doctors’ and drivers’; and crash scenes, pulled from vintage footage, although the footage does not always illustrate the point being made. The more you watch these crashes, the more they all start to look alike. Moreover, the average viewer might find themselves frustrated, particularly when the captioning of the accidents and the race car drivers is quick and inconsistent, or at times, non-existent.

Alex Zanardil’s crash is slightly different as Alex Tagliani’s car drove right through Zanardil’s cutting the car (the pieces spinning around like mixers) and Zanardil’s body in half. Olvey, who was not on the track, but on the premises, raced to the scene where Zanardil, whose legs had been cut off above the knee, had lost three quarters of his blood and was not expected to live. After multiple attempts to stop the flow of blood, Dr Olvey made the decision to send him to a Berlin trauma centre 37 minutes away by helicopter rather than a less specialised hospital that was much closer. Two years later, with prosthetic limbs, Zanardil was racing again (however, not in open wheel competitions). He acknowledges that he owes his life to Dr. Olvey’s fast medical intervention and wrote the preface to the 2006 book.

The most prominent talking heads belong to Dr Olvey (the organ man) and his associate, the affable, interesting Terry Trammel (the limb man), an orthopaedic surgeon who specialises in hands and feet. In addition to his practice, Trammel is a founding member of the International Council of Motorsports Science and a founding fellow of the FIA Institute for Motorsport Safety. Olvey is now an associate professor of clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, and vice chair of the University of Miami Hospitals and Clinics Ethics Committee and the Jackson Health System Adult Ethics Committee.

But if Dr Olvey ended up a specialist in medical ethics, the question of whether a doctor, dedicated to preventing and curing sickness and injury, should be a motor sports fan, patching up drivers to return them to the slaughter, does not come up. Nor was it an issue in the Olvey family’s Indiana living room when, one of the first families in the area to own a TV, they watched the races. When Stephen’s father took his two sons to the track, “we were in heaven,” even though the announcement that a driver had been “mortally wounded” went above young Stephen’s head. In those days, one in seven drivers were killed every year across the various motor sports.

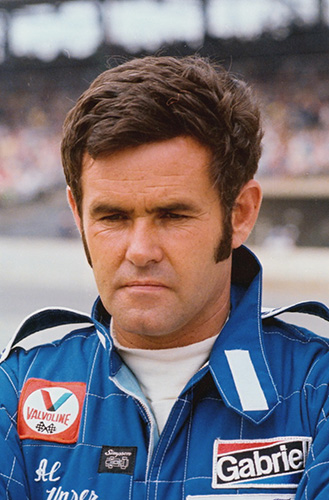

Bobby Unser, a three-time Indie 500 winner, recalls ‘Drivers kind of accepted getting hurt.’ Mario Andretti, who won the Indy Car Championship three times in the 1960s, is equally blunt: ‘that’s all we knew.’ Safety was an afterthought. Helmets (which were redesigned by Trammel and Olvey to protect the spinal column and brain) and seat belts were the extent of the routine safety measures in those days.

Fire was the biggest fear, until staff realised that there was an alternative to gasoline which exploded like a bomb, as illustrated (although not very clearly in the film’s grainy images) by the 1964 crash which killed Dave MacDonald and Eddie Sachs. Methanol is not safe but is less flammable than regular gasoline.

After graduation in 1969, Olvey was at a crossroads. He wanted to be a race car driver. His parents persuaded him to go to medical school. While still a student, he answered an advertisement for volunteers for the track and jumped at the chance, working under Thomas Hanna, credited with being the first doctor in the USA to put a hospital facility on the track. Olvey became Assistant Medical Director of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and, three years later, he developed the first US traveling motorsports medical team for the United States Auto Club (USAC). When Championship Auto Racing Teams (CART) separated from USAC, he became CART’s Director of Medical Affairs until 2003. Trammel joined Olvey in 1982.

Despite the limitations of the visuals, the film does a good job delineating the small, but significant steps taken toward improving safety. Astoundingly, this began with putting a doctor in the ambulance on the track. Previously, the track owners, mindful of costs, would wait for an accident to happen before calling a local undertaker’s hearse, ill-equipped to provide medical care in situ or en route to the hospital. The film covers the improvements to protocol, equipment, car design, and logistics. A doctor’s knowledge of the local hospitals and helicopter services was essential for track owners could not be trusted to, or expected to know the various options.

For obvious reasons, one of the most protracted segments deals with concussions. Parnelli Jones, Bobby Unser and Chip Ganassi (Olvey thought Chip was dead until he gradually responded to CPR) contribute to a mind-boggling discussion of the casual treatment of concussions prior to Dr Olvey’s investigations and improved detection procedures and their now standard, computerised “impact” test.

Toward the end of his time at CART, which ran the PPG Indy Car World Series from 1970 to 2003, Dr Olvey risked more than his career on an unprecedented decision to cancel a race at the Texas Motor Speedway, after a driver blacked out. Olvey quickly gathered evidence that drivers were becoming dizzy from the prevailing G-force measurement at the site. Many drivers, who were embarrassed to admit to being dizzy, were relieved when the race was cancelled. The fans were furious.

You can watch the film trailer here: