Joyce Glasser reviews On Her Shoulders (January 25, 2019), Cert. 12A, 94 min.

What were you doing on 3 August 2014? Packing for a summer holiday or a daytrip to the beach? At work and thinking about what to buy for dinner? Taking a summer school course? Working in the allotment? Visiting a friend in hospital or buying a new car?

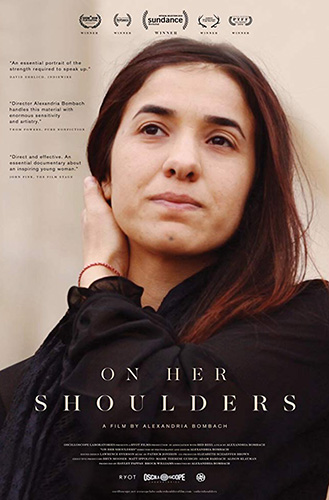

The subject of Alexandria Bombach’s gruelling, yet powerful and inspirational documentary, On Her Shoulders, is Nadia Murad. Nadia, now 23, thought that her 3 August 2014 would be an ordinary day, too. Instead, it led her on a path to unimaginable suffering and lasting trauma and to becoming the UN’s first Goodwill Ambassador who had actually survived sex trafficking.

A student living in Kocho, in the Sinjar district of Iraq Nadia helped out on the family farm, enjoyed making clothes and dreamt of opening a hair salon to show women how special they are. She never wanted to be known as a victim. Nor did she ever want to be an activist, politician or a spokes person for a vulnerable, forgotten religious minority scattered throughout intolerable refugee camps, primarily in Greece. But fate intervened. As the documentary shows, Nadia was left with no choice but to assume a position thrust upon her by circumstances and her selfless compassion.

A student living in Kocho, in the Sinjar district of Iraq Nadia helped out on the family farm, enjoyed making clothes and dreamt of opening a hair salon to show women how special they are. She never wanted to be known as a victim. Nor did she ever want to be an activist, politician or a spokes person for a vulnerable, forgotten religious minority scattered throughout intolerable refugee camps, primarily in Greece. But fate intervened. As the documentary shows, Nadia was left with no choice but to assume a position thrust upon her by circumstances and her selfless compassion.

Nadia was on her way home from school with a certificate to show her mother when ISIL attacked in their progressive campaign of genocide against the long-established Yazidi (non Muslim) minority. Many members of Nadia’s large, extended family were murdered on the spot. Almost all the village’s elderly women were killed; men were slaughtered and boys were either killed or taken to be trained as child soldiers. The younger women, some 7,000, including Nadia, were taken as sex slaves. Nadia was continually beaten and raped for three months.

Then she escaped. The documentary, which follows Nadia through a busy summer of 2016, leaves the horrific attack, capture, captivity and escape to her book, The Last Girl: My Story of Captivity and My Fight Against the Islamic State which we see her signing at the end of the film, her nails now manicured and polished.

Bombach is interested in the aftermath of her escape and Nadia’s unlikely path to becoming the first Yazidi and Iraqi to be awarded a Nobel Peace Prize in 2018. Though this ultimate prize was awarded after the film was completed, the reason for her joint (with Denis Mukwege) award, ‘[her] efforts to end the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war and armed conflict,’ is made clear in the film.

Gradually learning English and German (she resides in Germany), but relying at first on a steadfast friend and translator, we follow Nadia to the House of Commons in Ottawa Canada; to the UN headquarters New York, and then on a tour of squalid refugee camps throughout Greece. She repeats her story over and over, and each time, she has to relive the nightmare that has become her life. Each time she mentions rape, she thinks beyond herself to the 3,000 plus girls still missing, and to her nieces and cousins as young as 10 who were being raped alongside her.

When Nadia arrived in Germany she was offered therapy but declined. She did not feel right being singled out for help when so many others were still suffering, not just from PTSD, but from imprisonment and torture by inhumane brutes and from life in refugee camps. Her three surviving brothers and a sister are still in the camps. In a way, describing her ordeal and repeating her message to governments, television and radio reporters and human rights groups, is her therapy. Or at least, it is something she is compelled to do. In one of her camp visits she tells a young girl not to cry and announces to her people: “I swear this work will not be abandoned.”

Not surprisingly, Nadia seldom smiles. When she does it is to accept a compliment that she does not feel she deserves. Everything she does is to raise awareness of the plight of her people. Whenever she speaks she is dressed in black and tears fill her eyes. After the ceremony appointing her as a UN Goodwill Ambassador for the Dignity of Survivors of Human Trafficking, she says only, ‘I wish my mother was here.’

Lebanese-British human rights barrister Amal Clooney not only wrote the forward to Nadia’s book but was sitting beside her at the UN when she made her speech. Hopefully Ms Clooney is, as she acknowledges in the film, using her celebrity for Nadia’s cause. But at the UN, Bombach captures her bounding across the forecourt on her incredibly long, thin legs, heavily made up and immaculately coiffed and wearing an attention-grabbing, white designer dress with a striking red band in the middle, matched by an immense red patent-leather hand bag swinging in her hand. It looks more like a hat box than a briefcase. She towers above Nadia, who is dressed in non-descript black clothing with no accessories or no make-up.

Currently, working with Yazda, a Yazidi right organisation, Nadia is determined to bring ISIS before the International Criminal Court. She might one day open her hair salon in Kocho, which, as she discovers, now lies in ruins, but for the considerable future her peripatetic life is one of an activist. While no doubt pleased that her appointment gives her more of a voice and a platform to reach world leaders, she takes no credit: ‘I see myself as a worthless person until the day ISIS is brought to justice.’

One of the most memorable moments in the film occurs as Nadia is editing her big UN speech. “Take out ‘imagine’” she asks. “They cannot imagine.” We cannot imagine, but after seeing this film, we can admire, support and be inspired by a courageous girl who does not have to imagine crimes against humanity. She survived to tell the world about them.

You can watch the film trailer here: